It was on the journey to Burgundy that Martine de Bertereau’s oldest son Hercule fell ill. He had a “flaming heat in the intestines,” which was probably even worse than it sounds, given the state of medicine in 1627. The family was headed to the popular spa town of Pougues-les-Eaux, but that was still nearly 300 km (186 miles) away. They decided to stop where they were, Chateau-Thierry, to allow Hercule to rest and hopefully recover. But Martine couldn’t miss an opportunity to flex her mineralogy and water-divining muscles.

“Approaching Château-Thierry, and mounting the mineralogical compass on to the astronomical hinge, in order to find out whether there are any mines there, or minerals … I found the spring: whereupon having called the officers of the justice, the medical men, and the apothecaries of the city to see the proof of my test, and acknowledge the quality of these waters. Setting up the mineralogical compass in its catch over and near the springs, I let them see with their own eyes (and by definite proof) that the said fountain … [was] mineralized and drew medicinal qualities from passing some mine of silver containing gold and also from some mine of iron … [so] is therefore very suitable for relieving obstructions of the liver and spleen, to drive out stones and gravel from the kidneys, to stop dysentery and all flows of the blood, and to alleviate great impairments.”

How fortuitous! To find a mineral spring where they stopped and not have to trek all the way to the other spa town. After a few weeks, Hercule was well again, and before long, Château-Thierry became a popular spa town in its own right, attracting the chronically ill and wealthy wellness-seekers alike. But the town doctor, despite seeing Martine’s divining prowess with his “own eyes,” was suspicious. He dug a little further and found she had actually tracked down the mineral-rich water source by following the trail of iron-filled reddish deposits in the cobblestone.

Why would she claim ancient mystical knowledge when what she was actually using was sound geological science?

Martine was born sometime around 1590 in Touraine to a mine-owning family. She was highly educated: well-versed in geology, alchemy, chemistry, metallurgy, geometry, and hydraulics, and fluent in Latin, French, Italian, German, English, and Spanish. She took up the family business, and is believed to be the first woman mineralogist and mining engineer in recorded history.

In 1610, she married Dutch fellow mineralogist and mining engineer Jean de Chastelet, Baron de Beausoleil. Together, they became Europe’s foremost oremonger power couple. They were hired by archdukes, emperors, even a pope. In France alone, they claimed to have discovered 150 mines. Silver, lead, gold, iron, copper, and also mineral pigments, marble, coal, turquoise, rubies, opal,—they found them all using Martine’s simple steps:

Digging, which is the least important.

Look out for special herbs and plants, which may grow on an ore body. “We notice also that the most important places where mines can be found in this kingdom, are not very fertile, because the earth is occupied in nourishing the metals and minerals rather than the good plants.”

Consider the taste of the water, which emerges from springs in the vicinity of ore deposits.

Observe the vapours that are emitted from the mountains and valleys at sunrise.

The use of sixteen metallic and hydraulic instruments.

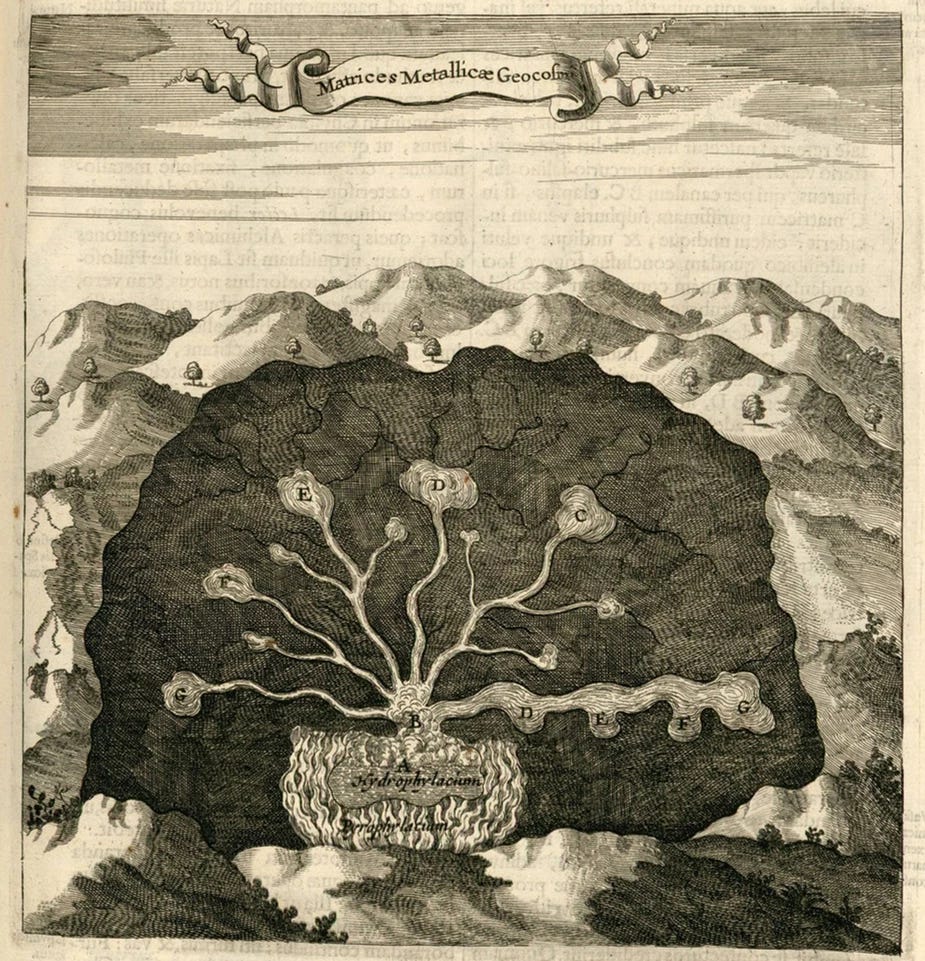

Martine divided the sixteen instruments into seven groups, which correspond to the seven astrological planets (Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn), each of which was then related to a certain type of stone or mineral. For example, a drawing compass was used to locate gold, which was related to the sun; a compass with seven waxed circles was used to find silver, which was related to the moon.

In addition, Martine lists sixteen(!) skills and crafts required to be a successful mine owner: astrology, architecture, geometry, arithmetic, perspective, drawing, hydraulics, labor and mining legislation, languages, medicine (to protect yourself from poisonous vapors), surgery (to help injured workers), botany, pyrotechnics, petrography, theology, and chemistry.

(These lists are given in Martine’s order, as related by French historian and mineralogist Nicholas Gobet in 1779, who essentially rescued her texts from obscurity.)

After a few years working for France, Jean was made commissioner of Hungary’s mines. For sixteen years, this work took the family all over Europe and even to South America in search of mineral deposits and fresh groundwater. Martine told harrowing tales of descending the deep mines of Potosí, in what is now Bolivia, and several mines in Hungary, in areas that are now Slovakia.

In her later works, Martine mentions seeing dwarves working in the South American caves. Scholars say this led to her work being taken less seriously by her contemporaries. But this was not merely a figment of her wild imagination. Myth and folklore suggested dwarves were friendly demons who came from within the Earth to help miners. Sightings were seen as a good omen for mining activities. This association was later popularized by the Brothers Grimm tale of Snow White. Athanasius Kircher’s 1665 two-volume publication Mundus Subterraneus, discussing the inner workings of the earth—“the fecund womb of Nature”—proved quite popular despite an entire chapter discussing demons that populated underground metal mines. Maybe Martine’s work was scoffed at because she was a woman?

In 1626, France decided it wanted the Beausoleils back. In high demand, the couple felt on top of the world. They triumphantly returned to France, bringing with them several experienced miners from Hungary and Germany. They left Hercule in charge of operations in Hungary. Expecting to soon be heartily compensated by the King, the Beausoleils invested 300,000 livres of their own money in setting to work surveying, setting up mining operations, and employing miners.

But suspicion soon found Martine again. At the mining base the couple established in Brittany, provincial priest Touche-Grippé was convinced they were practicing witchcraft. Mines could only be discovered using magic; they must have been consorting with demons. He had a bailiff ransack their home to find evidence to support his suspicions. The priest was particularly interested in finding a magic tool. Their research, specimens, charts, books, and tools were all confiscated, declared proof of their sorcery: the priest accused Martine and her husband of witchcraft. While no official charges were brought against them, they were forced to leave France in 1628. They lived for a time in Germany and then Hungary.

After the mess blew over, Martine and Jean once again returned to France. They had several children, but information only remains on their first child Hercule, and their oldest daughter, Anne, who was born in 1630. In 1632, Martine published her first text. Véritable déclaration de la découverte des mines et minières catalogued all of the mines and mineral deposits she and her husband had uncovered in France and described her use of divining rods to find water sources. Much of Martine’s advice about how to find water and where to dig is gleaned from the texts of first-century Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio.

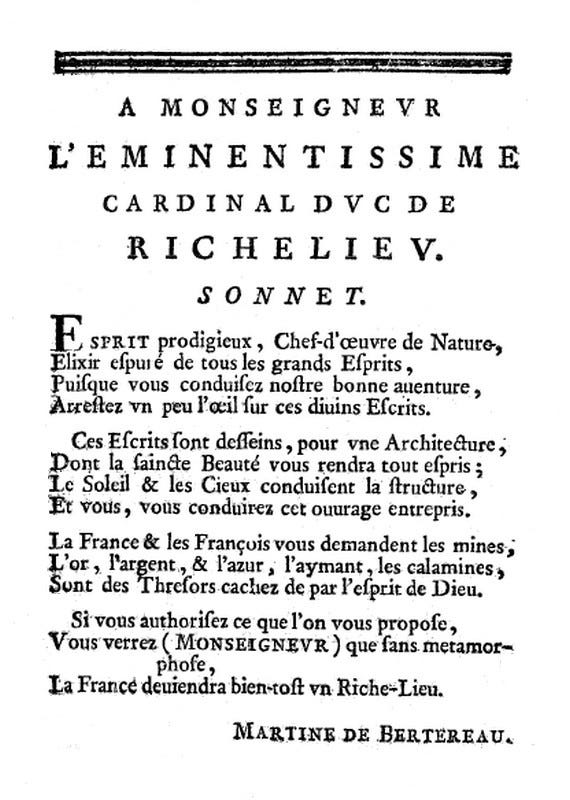

Despite all of their work for the French crown over fifteen years, the couple never received any payment. In 1640, Martine wrote La restitution de pluton, a Latin poem, which, among other things, served as a plea for payment, addressed to Cardinal Richelieu. More importantly, the text offers a defense of women in mining:

“But how about what is said by others about a woman who undertakes to dig holes in and pierce mountains: this is too bold, and surpasses the forces and industry of this sex, and perhaps, there is more empty words and vanity in such promises (vices for which flighty persons are often remarked) than the appearance of truth. I would refer this disbeliever, and all those who arm themselves with such and other like arguments, to profane histories, where they will find that, in the past, there have been women who were not only bellicose and skilled in arms, but even more, expert in arts and speculative sciences, professed so much by the Greeks as by the Romans.”

Two years after its publication, Richelieu had the family imprisoned on charges of sorcery. Historians blame either the text’s witchy, astrological overtones or the couple’s allegiance to his political adversaries for this sour turn of events. Jean went to the Bastille; Martine and Anne were ensconced in a Vincennes prison just outside the city. When Hercule came looking for his parents, he too was imprisoned.

Martine may have hoped that openly detailing their mining and divining practices in her texts would shield them from further scrutiny, but it seemed to have the opposite effect. Perhaps it was not the magic, but the request for money that Richelieu objected to. The Vincenne was reserved for prisoners of high birth or prominence; they enjoyed a minor measure of freedom. Fellow prisoner Jean du Vergier de Hauranne, abbot of Saint-Cyan, was struck by this proud woman in tattered clothes at the Vincenne chapel. After finding out who she was, he covertly arranged for new, warm clothing to be brought to baron and baroness. He also sent someone to check in on the welfare of their other children. Martine gifted him a copy of her book in return.

To this day, scholars ponder Martine’s “deception.” Why would she tell people she was finding mines with ancient, mystical practices when she was really only practicing sound science? I get the sense Martine was also a savvy businesswoman. She recognized that a dash of theatricality, a bit of mystery, and a touch of magic was the perfect recipe for notoriety.

Further Reading:

“How To Find Water: The State of the Art in the Early Seventeenth Century, Deduced From Writings of Martine de Bertereau (1632 and 1640),” by Martina Kölbl-Ebert, Earth Sciences History, vol. 28, no. 2, 2009.

“Alchemy at The Service of Mining Technology in Seventeenth-Century Europe, According to the Works of Martine de Bertereau and Jean du Chastelet,” by Ignacio Miguel Pascual Valderrama and Joaquín Pérez-Pariente, Bulletin for the History of Chemistry, vol. 37, no. 1, 2012.

“Divine Deception,” by Stephanie Pain, New Scientist, October 20, 2004.

More About Me:

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page

Order my book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, published March 2021 from HarperCollins/Park Row Books.

Buy a *signed* hardback copy online at Newtown Bookshop.