A Mother of 3 Maps the Brain

The life of trailblazing neuroscientist Cécile Vogt-Mugnier

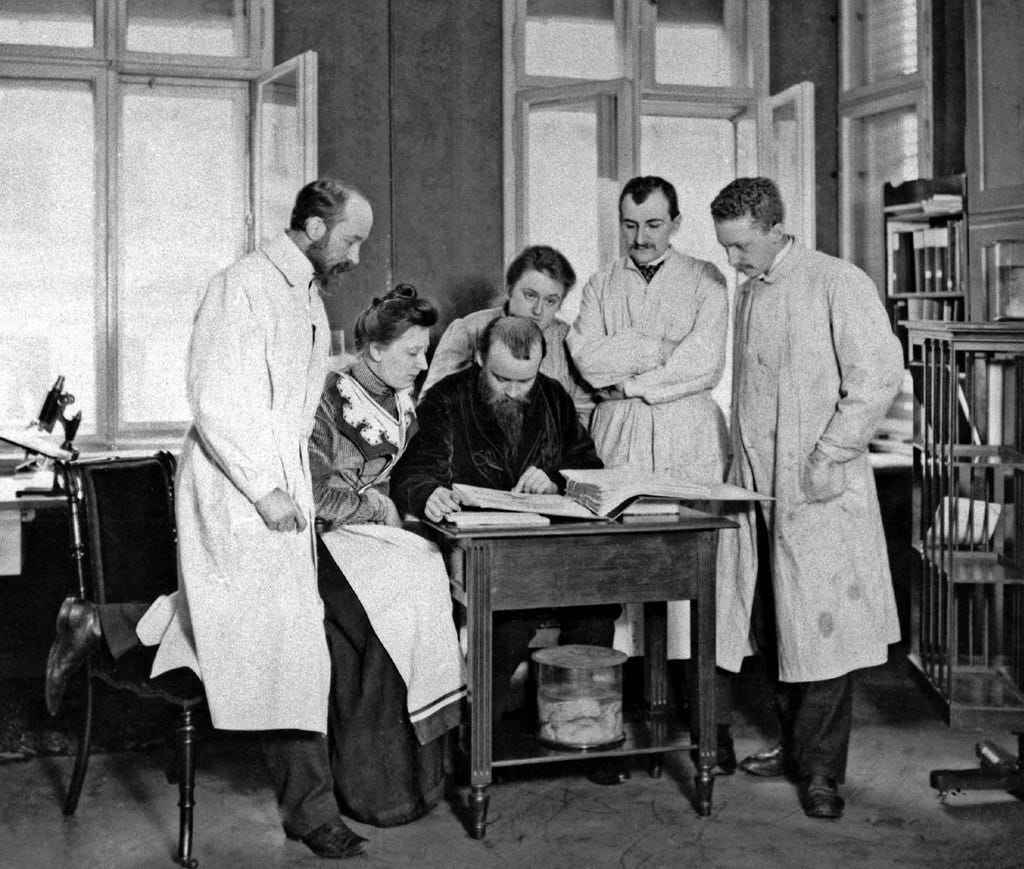

In 1897, 22-year-old Cécile Mugnier found herself pregnant, unmarried, and in the middle of earning a medical degree. That same year, she also met her future husband, Oskar Vogt. Cécile was working as an assistant to the eminent neurologist Pierre Marie when the short, dapper German scientist swept into Paris and into her life. Tall and witty, Cécile was learning about cortical localization from Marie and his team at the Bicêtre Hospital. By cataloguing the cortical location of the injury and the corresponding symptoms, they hoped to find which regions of the brain controlled which bodily functions.

Oskar was a country physician who’d been traveling around Europe studying neuroanatomy, psychiatry, and hypnotism. He used hypnosis to treat patients with neurosis and anxiety. Now, in Paris, he was studying brain anatomy in the laboratory of Augusta and Jules Dejerine at the Salpêtrière Hospital.

The pair hit it off at once, thanks to their shared scientific interests and despite their language difference. Cécile soon moved to Berlin with Oskar. Though she hadn’t finished her Paris degree yet, she continued working toward it after moving. She gave birth to a daughter, Claire, in June 1898. Oskar and Cécile got married the following year; Oskar adopted Claire when she was 4 years old.

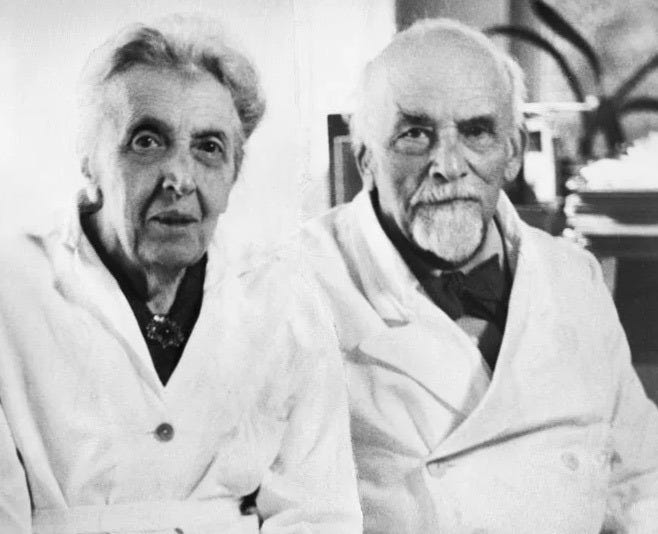

So it was with 30 human brains (generously gifted to the happy couple by Marie), and the shared dream of unlocking all of their secrets that Cécile and Oskar began their personal and professional partnership. Theirs was a collaboration that would last an incredible 60 years and endure two world wars. Together, they would map the human brain.

“It was not easy to get close, on a human level, to Dr Cécile Vogt’s highly intellectual nature,” a former colleague once noted. “This cool matter-of-fact manner concealed a warm heart, however.”

Augustine Marie Cécile Mugnier was born in Annecy, France in 1875. Her parents weren’t married, and her elderly father died when she was just 2 years old. That left Cécile to be raised by her aunt, who was rich, but staunchly religious. Cécile rebelled against the religious education she was given and rejected her aunt’s assumption that she would eventually become a nun. She hired private tutors to prepare for her baccalauréat exams. At 18, she was off to Paris to study medicine.

Cécile finally earned her doctorate in 1900 after completing a dissertation in neuroanatomy. It had been a good three decades since women were first allowed into medical school in Paris, yet when Cécile got her MD, only six percent of medical doctorates were being awarded to women.

Their first lab, which they dubbed the Neurological Central Station, was born in the living room of their 3-story apartment in downtown Berlin. Their goal was to find out which region of the brain corresponded with which physical and psychological functions: they were certain there was a neuroanatomical basis for psychological phenomena and that structural differences would correlate to functional differences. They hoped such information could be used to treat psychological disorders as well as determine what was behind exceptional talent or genius. It was privately funded by a steel magnate at first. His money paid for them to take over the entire building and construct cages and safety nets for their research monkeys.

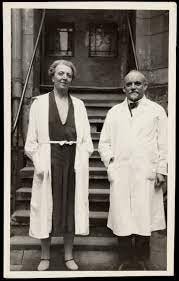

In 1902, their lab expanded. It was renamed the Neurobiological Laboratory and financially associated with the Friedrich Wilhelm University. The couple worked late into the night, sitting at a paired writing desk where they faced each other while working. They are likely among the first people to have used the term “neurobiology.”

By this time, they had two daughters. Cécile had given birth to Marthe in 1903. It was only by employing housekeepers and nannies that Cécile and her husband were able to continue their work. With the lab’s new annual budget of 30,000 Marks, Cécile hired a team of female technicians and set to work on the lengthy, painstaking process of tracing each and every connection in the brain. The subsequent collection of thousands of human and animal brain slices (and related illustrations) became the largest in the world. It’s now housed in the Cécile and Oskar Institute of Brain Research in Dusseldorf.

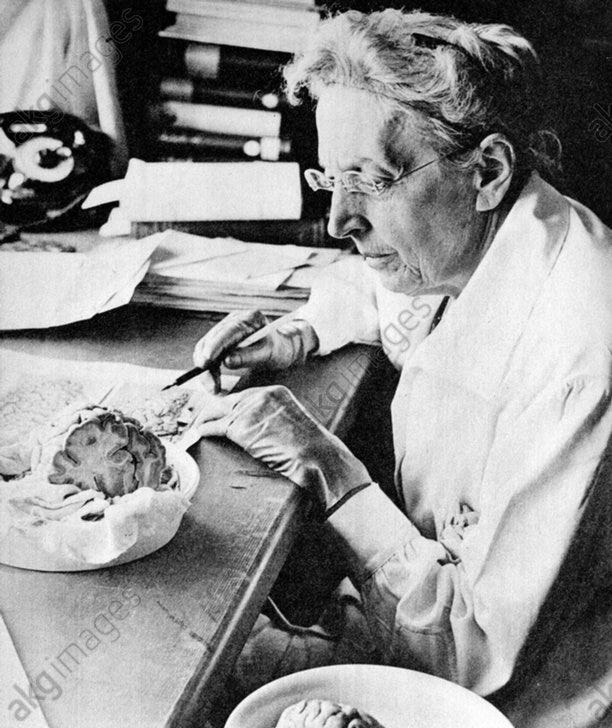

The Vogts work used brain architectonics, which looks at the number, shape, size, and arrangement of the nerve cells in the cortex. That labor soon bore rich fruit. In a landmark paper co-authored by the Vogts in 1907, the motor and sensory cortices were first identified as two distinct areas.

In 1913, the couple had another daughter, Marguerite. Just as their family grew, so did their lab. The following year, Cécile and Oskar established the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Brain Research (KWI): He was appointed director and she was named head of anatomy. In 1925, Oskar famously dissected Vladimir Lenin’s brain. Their lab moved to an expansive campus in the Berlin suburbs in 1931; later, it would make one final metamorphosis into the Max Planck Institutes for Brain Research.

Cécile began focusing on the role of the thalamus, the area that would later be named the basal ganglia, and the extrapyramidal pathways. She collected brains of people who had diseases related to damage in these areas. Through her studies, she discovered that structural differences were related to movement disorders like Huntington's disease and that lesions could lead to infantile pseudobulbar palsy.

Cécile and Oskar’s most lasting, impactful contribution came from work with their longtime collaborator, Korbinian Brodmann. After decades of work, the trio announced they’d identified 200 separate regions in the cortex. Brodmann’s cortical area classification remains in use today. It was an incredible breakthrough, but it still didn’t connect regions to functions, so their work was far from done. To make these connections, Cécile applied electrical stimulation to different areas of the cortex. She was actually one of very few scientists using this technology at the time. Monkeys were the test subjects for the most part. Finally, they combined their findings together to create a brain map illustrating both structure and function.

“It was the genius of Cécile, which, at this critical period of the ‘Neurobiological Laboratory’, provided the cement which allowed to solidify these new ‘fluid’ observations into a new understanding about the interrelationship and interaction of various synchronously working region of the brain,” claimed Igor Klatzo, a scientist who worked with the Vogts. “The cement was Cécile's morphological work on the extrapyramidal system, which had fascinated her already in Paris.”

Still, because she was a woman, and French no less, Cécile was a bit of a pariah in the German science scene. France was a former enemy, and nearly all of the medical men in Berlin did not think women should study medicine. She had to fight tooth-and-nail to be allowed to attend science conferences. Cécile only held a formal, paid position between the years 1919 and 1937. The rest of the time she worked for free, relying on her husband’s income.

Sexism meant that it wasn’t until 1920 that Cécile was finally awarded a license to practice medicine in Germany. Throughout her research, Cécile used science to counter the widely held belief that women were inherently intellectually inferior. In the 1920s, she announced that her research had not revealed any difference between male and female brains.

While Cécile may have been a true scientific genius, her success and impact have to be measured in the context of her marriage. That is, you have to see her access to well-appointed labs and leadership positions was through the privilege of a scientist husband. Most women scientists at the time found themselves at the mercy of domineering, egotistical bosses who stole their work or assigned them the rote tasks no one else wanted. If they could find a job at all. And they were certainly expected to quit when they got married and had children. Cécile is remembered by virtue of being married to a man who respected her as a scientific equal and had the funds to create labs where she had free reign.

All three of their daughters became scientists. Claire was a pioneering pediatric neurologist and neuropsychiatrist in Paris. Working in the UK, Marthe was one of the leading neuroscientists of her century. She specialized in neurophysiology and was interested in finding pharmacological treatments for mental illness. She was also the ninth woman ever elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. Marguerite went to the California Institute of Technology, where she and colleague Renato Dulbecco founded the field of molecular virology. They also discovered that the polio virus created plaques on tissues. For their work, Dulbecco alone received the Nobel Prize.

There was a good reason why none of the Vogt girls ended up working in Germany. Their parents were unabashedly leftist; pacifists who employed women and Jewish people at their institute. In Germany in 1933, these things made them a Nazi target. Marthe and Marguerite were both working at their parents’ lab when the SS raided it. Oskar was accused of being a communist sympathizer and fired. A Nazi physician replaced him as head of the institute. Berlin was no longer safe.

Cécile and Oskar were off to Neustadt, a spa town by a lake in the Black Forest, to establish the Brain Research and General Biology institute. It wasn’t just for their own benefit. For others fleeing persecution, they offered jobs and refuge. They remained there even after the war was over, and continued to make contributions to the fields of neuroanatomy and neuropathology.

** Most photos courtesy Wellcome Collection, London. **

Further Reading:

“Cécile Mugnier Vogt,” Untold Stories: the Women Pioneers of Neuroscience in Europe.

“Cécile Vogt,” Life in the Fast Lane, by Kathryn Scott & Mike Cadogan, Nov. 14, 2020.

Cécile and Oskar Vogt: The Visionaries of Modern Neuroscience by Igor Klatzo, 2002.

More about me:

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page

Order my book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, out March 2, 2021 from HarperCollins/Park Row Books.

Buy a *signed* hardback copy online at Newtown Bookshop.