A Prodigiously Prolific Author, Illustrator, and Translator

Sarah Bowdich Lee's (1791–1856) incredible contributions to natural history

Sarah Eglonton Wallis and her two brothers lived a comfortable life with their parents in Colchester, England, until their family abruptly went bankrupt in 1802. Little Sarah was only 10 years old at the time. The family fled to London in shame. Against her family’s wishes, Sarah married naturalist T. Edward Bowdich eleven years later. Sarah was actually three months older than Edward.

The couple welcomed a son later that year, but he died in infancy. Next came a daughter, Florence. But before she gave birth, Edward was off to what is now Ghana in his capacity as a writer for the Royal African Company. Not to be outdone, Sarah showed herself even more intrepid by setting off to join him after Florence was born—with Florence in tow. Unfortunately, Edward had already begun his return journey by the time they arrived in Cape Coast. Whoops!

In 1818, they spent some time together in Ghana, during which Florence died of a fever. The following year, Edward published a book that served to inform Britons about Ghana’s geography, flora and fauna, culture, politics, and customs. Sarah clearly contributed to the volume.

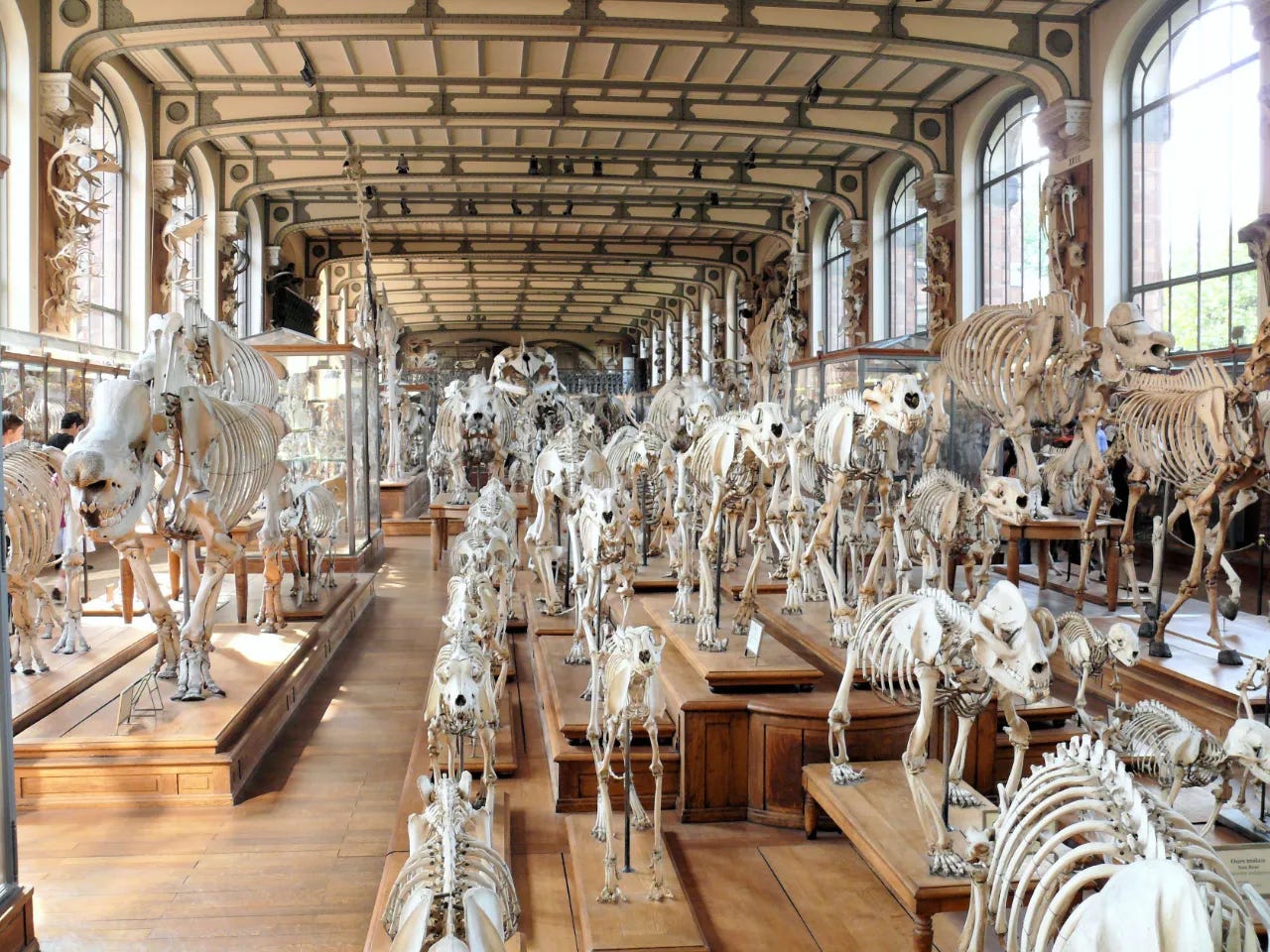

Back in Europe, the Bowdiches decided it was time to visit Paris to learn what they could from the internationally renowned collection at the Jardin des Plantes and from Alexander von Humboldt, Jean-Baptiste Biot, and Baron Georges Cuvier. Cuvier was a zoologist, naturalist, and professor of comparative anatomy at the Museum of Natural History who’s often referred to as the father of paleontology. He’s also known for performing examinations on Sarah Baartman, a South African woman forced to appear in freak shows in Europe.

The Bowdiches spent most of the next four years studying alongside Cuvier in his Gallery of Comparative Anatomy and associated laboratories. He had large collections of animal specimens, including many from Africa, as well as an extensive library of natural science texts. It was at Cuvier's Saturday salon that Sarah and Edward rubbed shoulders with the most illustrious scientists and artists of the day, from across the globe.

The couple planned to use what they learned to help them prepare for their next African expedition: an excursion to Sierra Leone that they would undertake independently since The Royal African Society refused to bankroll it.

Before they could mount any plans for their journey, they needed to make money to pay for it. During those four years in France, Edward published more than a dozen texts in English describing the latest findings in French science and detailing scientific expeditions to West Africa. For these books, Sarah did much of the translation work in addition to providing over 600 illustrations of the specimens she observed in Cuvier’s museum and labs.

That she was even allowed to enter these rooms as a woman was truly remarkable. She must have been a truly exceptional scientific talent to have proven herself indispensable enough for the men to have permitted her not only to enter the lab but to participate in the creation of texts about it. Her linguistic and artistic skill is apparent.

Both Sarah and Cuvier’s wife, Anne-Marie, had lost children in childbirth or infancy. Between 1804 and 1813, only one of the four babies Anne-Marie birthed survived. Sarah had already lost two babies. While in Paris, she birthed three more children, one of which died. Sarah was also very close with Cuvier’s stepdaughter, Sophie.

In 1820, Sarah also finally became a published author in her own right. Her book Taxidermy; or, the Art of Collecting, Preparing, and Mounting Objects of Natural History, was an exhaustive manual that saw six editions. Much of the text was translated from the work of Louis Dufresne, a taxidermist and curator at the Museum d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris.

In the book, she also discusses Charles Waterton, an eccentric English naturalist and conservationist who turned his vast country estate into the world’s first wildfowl nature reserve. Sarah found Waterton very hospitable when she visited his property. She decided to include his methods of preserving animals in her text since they were so unique. Waterton taxidermied creatures by first soaking them in what he called “sublimate of mercury,” a highly toxic chemical. His techniques gave his creations a more lifelike feel that greatly contrasted with the typical overstuffed-looking animals turned out by his contemporaries.

The Bowdich family set out for Sierra Leone in 1823, by way of Madeira, this time traveling all together. When they left, their eldest daughter, Tedlie, was 3 years old, and little Hope only a few months old. Plus, Sarah was heavily pregnant. Their daughter Eugenia was born in Madeira. The new family of five left Bathurst on the River Gambia but failed to reach their destination.

Surveying the River Gambia proved too taxing for Edward. He came down with a fever and died in January of suspected malaria.

Sarah and her three young daughters returned to London a few months later. The crates of flora and fauna specimens they collected on their trip, all of which would’ve been new to European science, were ruined by terrible storms. Had they not been lost, this donation would’ve served as Sarah’s entry ticket to the British Museum as a respected scientific explorer. As it was, she was now merely a widow and young mother.

To manage her grief, Sarah dedicated herself to completing and publishing the travelogue her husband had begun. In addition to finishing the narrative of their journey, she added descriptions of the English settlements along the Gambia River and an appendix brimming with descriptions of local flora and fauna that she also depicted with detailed sketches and paintings. Excursions in Madeira and Porto Santo was published in 1825.

Sarah also spent more time with the Cuviers, who treated her like a daughter and helped her get back on her feet. In 1829, she got married again, to Robert Lee. Sarah devoted the rest of her life to popularising natural science, helping to keep her little family afloat financially with her publications, despite not having a room of her own in which to study and write. Her books were aimed at general audiences, both adults and younger children, to help make science topics accessible and approachable. To call her prolific would be an understatement.

Sarah’s numerous publications include Adventures in Australia, The African Wanderers, Fresh-Water Fishes of Great Britain, Trees, Plants, and Flowers: their beauties, uses, and influences, and Anecdotes of the Habits and Instincts of Birds, Reptiles, and Fishes. She also wrote several short stories and slim volumes on natural history, African culture, British and foreign birds, trees, and animals. Many of her stories feature African protagonists and female heroes overcoming injustice, showing that she was an abolitionist and feminist.

Fresh-Water Fishes was the first book to use Cuvier’s new fish classification system and to feature specialist hand-painted illustrations of freshwater fish. The book was published as a series in twelve parts between 1828 and 1838, with each part featuring four fish. The fish were caught just for her: Sarah assessed the colors of the fish and recreated them with paint immediately after being caught; the colors would’ve faded if she waited. A guinea per part, the series had fifty subscribers, including the Duke of Sussex. Cuvier noted that “no more exquisite drawings of fish coloured according to nature have yet been published.”

She also helped popularize “gift books” among England’s elite. Originally a German concept, Sarah wrote a story for Forget Me Not, the first gift book published in Great Britain.

“Its florilegium format—stories, poems, landscape descriptions, architectural and historical cameos, educational tales, articles on art and culture—was designed to entertain and educate the genteel young woman reader. Gift books came only in luxury formats, with a binding of leather or silk, with a design appeal for female purchasers and recipients that elevated taste and accomplishments,” explains Professor Mary Orr of the University of Southampton, who wrote the first full-length text on Sarah’s life (publishing in July 2024). “To add to their drawing room status as beautiful and rarer objects of display (reflecting their owners), gift books were liberally illustrated with expensively produced lithographs. The commissioning of stories and artwork from well-known writers and illustrators was part of their continuing attraction and value. The immediate success of ‘Forget Me Not’ spawned a host of rivals and imitators.”

When Cuvier died, Sarah prepared and published his biography, “Memoirs of Baron Cuvier.” It was a great loss for Sarah, both personally and professionally, but at least she had her daughters and her new husband to help her through it.

Sarah is an exemplary example of an early woman scientist who gained entry into the field via her husband, and thanks to Cuvier’s openness to women in science. But it was her advanced scientific and linguistic intellect that truly allowed her to move freely in these circles and to support her family financially.

Further Reading

Sarah Bowdich Lee (1791-1856) and Pioneering Perspectives on Natural History, by Mary Orr. Anthem Press, July 2024.

“Women peers in the scientific realm: Sarah Bowdich (Lee)'s expert collaborations with Georges Cuvier, 1825–33,” by Mary Orr. Notes Rec Royal Society of London. Vol 69 Iss 1, pp. 37–51. Published online Nov 2014

“Writing natural history for survival—1820–1856: the case of Sarah Bowdich, later Sarah Lee,” by Donald deB. Beaver. Archives of Natural History, Vol 26 Iss 1, pp. 19-31. Published online July 2010.

More About Me

Olivia Campbell is the New York Times bestselling author of Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine and the forthcoming Sisters in Science: How Four Women Physicists Escaped Nazi Germany and Made Scientific History.

She is an editor at Dotdash Meredith and a thesis advisor for Johns Hopkins University's science writing program. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, The Atlantic, The Guardian, Washington Post, New York Magazine, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, and HISTORY, among others. She lives outside Philadelphia with her husband, sons, and cats. Find out more on her website.