For four long years, Booker T. Washington had been searching for the right person to act as resident physician at his Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. He finally reached out to the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania to see if they could recommend anyone.

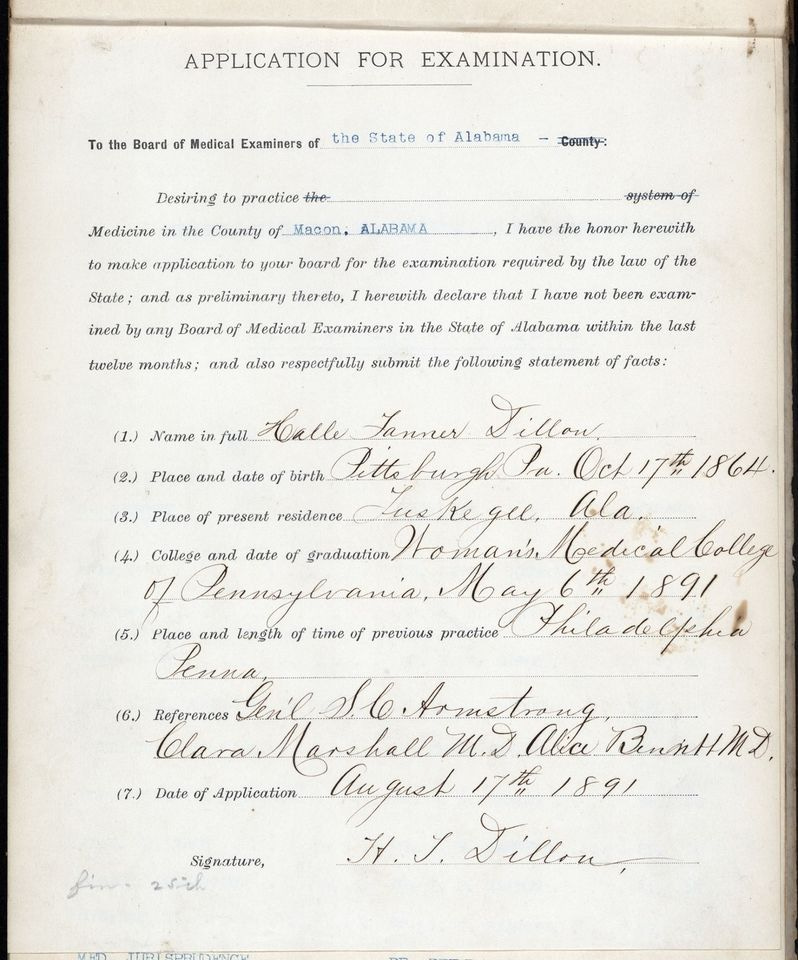

Halle Tanner Dillon was just the woman for the job. Washington wrote to her personally to request she take on the position. She headed south in the thick of summer, August 1891, just a few months after earning her MD. Several women of color had studied at the WMCP since its founding in 1850, but that year, Halle was the only Black student in her class.

Halle was born in Pittsburgh in 1864, the first daughter of Benjamin Tucker Tanner and Sarah Elizabeth Tanner. The couple were active, prominent members of the community; Benjamin was a bishop in Pittsburgh’s African Methodist Episcopal Church. The children were well educated and Halle helped her father publish the church’s newspaper, the Christian Recorder.

At 22, Halle married Charles Dillon. Two years later, the couple welcomed a baby. But Charles died suddenly, leaving Halle a widow at 24. Needing a way to support herself and her child, she headed off to medical school. After three years, she graduated with honors. She was incredibly fortunate to be headhunted for a job so soon after graduating. Many women MDs of the era found hospitals and doctor’s offices were wary of hiring them, simply because they were women.

Halle’s new post at the Tuskegee Institute involved providing medical care to 30 faculty and staff members and their families, as well as 450 students. In addition, she taught two classes a day. For all of this work, she was paid $600 a month and provided with room and board. But before she could practice medicine in the state of Alabama, Halle had to pass a grueling, lengthy examination. To prepare for the ordeal, Washington arranged for her to spend time studying under Montgomery physician Cornelius Nathaniel Dorsette, one of the first licensed Black MDs in the state. A Black woman taking the medical licensure exam caused quite a stir in Alabama.

When she felt she was ready, she headed into the exam on August 17. But that was just the first of the nearly ten-day exam. In total, she was quizzed on ten different medical subjects by ten different examiners, most of whom were the top experts in the state. There were oral, typed, and handwritten portions.

She passed! Halle excitedly wrote to her mentor, WMCP dean Clara Marshall, to share the good news. News of Halle’s success echoed across the country.

The New York Times reported that in passing this “unusually severe” test, Halle became "not only the first colored female physician, but the first woman of any race to pass the Alabama State medical examination.” Halle’s application and exam can now be read on the Alabama state archives.

Even with all of her responsibilities at Tuskegee, Halle found time to give back to her community. Recognizing the dire need for high-quality healthcare, Halle founded the Lafayette Dispensary and opened a nursing school.

On May 1, 1894, Halle submitted a report on her work and observations, which was published in the Report of the Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual Meeting of the Alumnae Association of the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania.

“Tuskegee is a retired little town, situated 40 miles east of Montgomery. There are found many suffering with diseases brought on by non-observance of the laws of health; for this is a portion of the South known as the ‘Black Belt,’ and black it is, not only with People of this despised hue, but black with disease and death.

In the vicinity of our school are hundreds in need of medical attention. Children with tubercular tendencies, sore eyes, various skin troubles, and in a pitiable condition generally. Women with faces bearing the marks of pain upon them; faces which testify but too plainly that life is a burden with such diseased bodies. Among them the most abject poverty, the blindest ignorance and the deepest apathy prevail. There is often the most stolid indifference as to the fate of the sick. This condition is to be largely attributed to the fact that medical attention, as a rule, is beyond the reach of but a few. The doctors charge $2.00 per mile for a visit, and this does not include the medicine.Now, where a person—as the majority of these do—lives ten or twelve miles in the country, and the doctor must be assured of his money before coming, often demanding cash, it is simply impossible for them to think of employing a physician. They bow their heads to the inevitable and say: “The Lord’s will be done.” Sometimes, when able to go to the doctor, this is done; even then the price is considerable and the skill questionable. Others drag out a miserable existence from day to day until relieved by death.

The idea of establishing a dispensary at Tuskegee, is one which has been growing for a year or more, but circumstances have prevented its development. At last a friend in the North kindly donated a sum sufficient to put our ideas into definite shape. And so we have begun with scarcely anything to back us, but faith that such a project will succeed because of its great need and noble aim—the saving of lives. ... the Lafayette Dispensary will soon be a fountain of health to the weary and sick of Macon County.”

Also in 1894, Halle got married again. John Quincy Johnson was a math professor at the Tuskegee Institute. Over the next six years, the new couple moved around a lot while John completed his theology education: first to Columbia, South Carolina, then to Hartford, Connecticut, Atlanta, Georgia, and Princeton, New Jersey. Along the way, the couple had three children. In 1900, they made a final move to settle down in Nashville, Tennessee. Halle opened up her own medical practice and John became minister of Saint Paul's AME Church.

But their happy existence was cut short when Halle died on April 26, 1901 from complications related to the birth of her fourth child.

Halle is mentioned in the 1904 book, Evidence of Progress Among Colored People: “As a splendid type of noble womanhood I know of no better subject than Dr. Hallie [sic] Tanner Johnson. She is a daughter of Bishop B. T. Tanner, of the A. M. E. Church, who is justly proud of her.”

Halle was an incredible testament to what Black women could achieve when given the opportunity to study medicine. She is also an important example of how the first BIPOC women MDs often made a point to raise the quality of healthcare in their communities.

Further Reading:

“Examining Drexel’s Ties to the First African-American Women Physicians,” Alissa Falcone, February 26, 2016, Drexel Now.

“Dr. Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson,” Changing the Face of Medicine, National Library of Medicine.

More about me:

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page

Pre-order my book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, out March 2, 2021 from HarperCollins/Park Row Books.