A Superlative Surgeon in the Segregated South

Dorothy Lavinia Brown accumulates an impressive collection of firsts.

It was a visit to the hospital for a tonsillectomy at the tender age of 5 that first sparked Dorothy Lavinia Brown’s interest in medicine. She was excited, utterly fascinated. Little did she know she would go on to become the first Black woman surgeon in the American South, spending 24 years as the chief of surgery at Nashville’s Riverside Hospital.

Dorothy was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on January 7, 1914. Her single mother, Edna, soon moved her little family to upstate New York, but found herself unable to care for Dorothy, so she placed her in the Troy Orphan Asylum (later renamed Vanderhyden) when she was five months old. It was largely populated with white children.

Her mother returned to claim her when Dorothy was 13 years old, but it was not a joyful reunion. Dorothy ran away from her mother’s home five times in two years, returning to the orphanage each time. After one such return, she was placed as a live-in mother's helper for Mrs. W.F. Jarrett, who actively encouraged Dorothy in her dream of becoming a doctor. Her final runaway act was to enroll in Troy High School at age 15. The school principal soon discovered she was homeless and saw to it that she be taken in by foster parents Lola and Samuel Wesley Redmon. The support and security the family provided made an incredible impact on her life.

Dorothy worked at a laundromat, and worked even harder at school. She graduated as class valedictorian in 1937. In her application letter to Bennett College, a historically Black women’s college associated with the Methodist church in Greensboro, North Carolina, Dorothy credited her foster parents for helping to guide and shape her into the person she’d become.

Dorothy began working as a domestic servant after graduation. One employer, the Women’s Home Missionary Society of the Troy Conference, saw that she was destined for better things and saw fit to award her a full scholarship to Bennett College noting: “Dorothy is worthy and has ability that needs to be developed.”

The next decade or so was spent bouncing back and forth between New York and the South. She graduated college in North Carolina in 1941, second in her class. To save money for medical school, during WWII she spent a few years working as an inspector at the Army Ordnance Department back in New York. With that money and some more financial aid from the churchwomen, Dorothy attended the historically Black Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee.

She graduated from Meharry in 1948 in the top third of her class, then headed back to New York for an internship at Harlem Hospital. Still, the institution refused to allow her a surgical residency because of her gender.

While women had been practicing medicine in America for nearly 100 years by 1940, the profession was still rife with sexism. Between 1900 and 1940, the total number of practicing physicians increased by more than 30,000, yet the number of women physicians only rose from 7,387 to 7,708. Opposition specifically to women surgeons had remained strong since the early days of women doctors. Women surgeons were incredibly few and far between when Dorothy was in medical school. Even as late as 1980, women only made up about 2 percent of all surgical residents in the US.

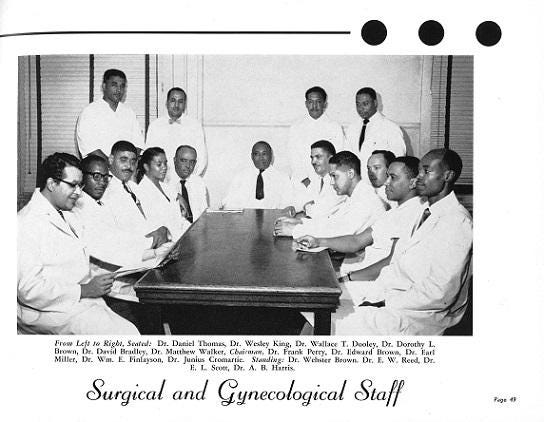

Dorothy went back to Nashville, and thanks to the support of Matthew Walker, Sr., chief surgeon at Meharry’s Hubbard Hospital, she was awarded a residency in general surgery. Walker saw promise in Dorothy, and so in spite of his staff’s insistence that a woman would never be able to withstand the rigors of a surgical career, Walker chose to take a chance on her. As the first Black doctor elected as a fellow of the American College of Surgeons, Walker likely knew the importance of someone taking a chance on you.

“Dr. Matthew Walker was a brave man,” Dorothy once said of his decision to allow her into the residency program. Walker’s gamble paid off: After a successful residency, Dorothy did not return to New York this time, but chose to remain in Nashville. That meant in 1955, Dorothy became the first Black woman surgeon in the South.

An incredible feat, to be sure, but even more incredible when you consider how the South was still deeply segregated at the time. It would be five years before the Nashville sit-ins began, to protest racial segregation at downtown lunch counters. The Civil Rights Act was almost a decade away. Dorothy had climbed a towering mountain of racism and sexism, and come out on top of the world.

When a young, pregnant patient begged her to adopt her baby, in 1956 Dorothy made history again by becoming the first single woman granted the right to become an adoptive parent in Tennessee. She named the baby Lola in honor of her foster mother. Later, she adopted a son named Kevin.

From 1957 to 1983, Dorothy served as chief of surgery and educational director at Riverside Hospital, clinical surgery professor at Meharry, educational director for the Riverside-Meharry Clinical Rotation Program, and an attending surgeon at Hubbard, Nashville Memorial, and Metro General Hospital. In 1959, she became one of the first Black woman elected a fellow of the American College of Surgeons. She was affectionately known as “Dr. D.”

“I tried to be not hard, but durable,” Dorothy explained of her incredible drive to persevere in an all-male profession where she faced both sexism and racism. She said she was proud to be a role model, “not because I have done so much, but to say to young people that it can be done.”

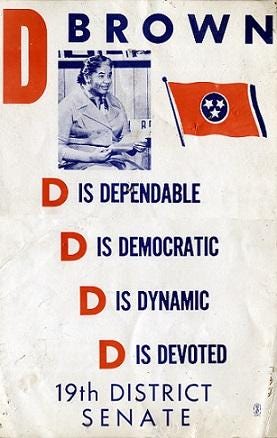

Another first Dorothy can claim is the title of first Black woman to serve in the Tennessee state legislature. She was elected to a 2-year term in 1966, but her sponsorship of a bill expanding abortion rights meant she lost her subsequent bid for state Senate. Dorothy knew the bill had the potential to save many lives, and was incredibly frustrated that it didn’t pass. It only fell short of passing by 2 votes; it would’ve permitted abortion in cases of rape or incest. One piece of legislation she sponsored, which was another issue she was passionate about, was successful: Dorothy helped pass a law permitting single women in Tennessee to adopt children.

She went on to make a difference in many other ways, and was especially interested in making medicine more hospitable to women in general and Black women in particular. Dorothy served on the Opportunities for Women in Medicine joint committee (sponsored by the American Medical Association) and as a consultant for the National Institutes of Health.

“My basic philosophy of life is the belief that we are here for a purpose—each of us being endowed with multiple talents; our charge is to develop one or as many of these talents as possible and to use these talents and the days of our living to glorify God. Therefore I must ‘Run to Live,’ and I must seek to serve in as many different areas of endeavor as I can,” Dorothy said.

The Carnegie Foundation bestowed her with a humanitarian award and she also received the prestigious Horatio Alger Award, among other accolades. The women's residence at Meharry is named in her honor.

After Dorothy’s death at the age of 90, Dr. John Maupin, president of Meharry Medical College, told the Tennessean newspaper: “Our nation has lost one of its greatest forces in medicine. Through determination and perseverance and with support of the Methodist Church, Dr. Dorothy Lavinia Brown opened doors previously closed to females and people of color.”

Tennessee representative Jim Cooper declared: “Dr. Brown was not only a brilliant surgeon but a compassionate one.”

In 2017, Dorothy was inducted into the Tennessee Health Care Hall of Fame, the following year, a historical marker was placed.

Further Reading:

“From a Troy Orphanage to a Pioneering Medical Career: Pathbreaker Dorothy Lavinia Brown,” by Reed Sparling, ScenicHudson.org.

“Nashville Women Whose Names You Should Know,” Nashville Public Library, February 22, 2020

“Dr. Dorothy Lavinia Brown,” Changing the Face of Medicine, National Institutes of Health’s National Library of Medicine.

More About Me:

Olivia Campbell is a journalist and author specializing in women, history, and science. Her first book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, was published March 2021 by HarperCollins/Park Row Books.

Buy a *signed* hardback copy online at Newtown Bookshop.

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page