A Thrill-Seeking Pathologist

Thank Anna Wessels Williams for our diphtheria and rabies vaccines.

Anna Wessels Williams had been working as a schoolteacher for a few years when, in 1887, her sister Millie experienced a brush with death. During childbirth, Millie lost her baby and nearly died herself, of postpartum preeclampsia, all thanks to the bumbling ignorance of an incompetent rural medical practitioner. That experience changed not only Millie’s life, but Anna’s as well. Anna decided to go into medicine, in hopes of preventing other women from going through what Millie had.

She said she became determined “to find out about the what, why, when, and where and how of the mysteries of life. This trait had increased with the years, and finally had become a passion.” Anna entered the Woman’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary, a school established by sisters Emily and Elizabeth Blackwell just two decades prior.

“I was starting on a way that had been practically untrod before by any woman. My belief at the time in human individuality, regardless of sex, race, religion or any factor other than ability was at its strongest. I believed, therefore, that females should have equal opportunities with males to develop their powers to the utmost,” Anna proclaimed. Between 1870 and 1880, the number of women physicians in America had risen sharply—from about 500 to about 2,400—but they still accounted for only a small fraction of the doctors practicing in America.

At school, she found a brilliant, caring mentor in physician and educator Mary Putnam-Jacobi. After graduating in 1891, Anna taught pathology and hygiene at the college and worked as an assistant at the Infirmary’s dispensary. Like many women medical graduates of her time, she then sought further training in Europe, making stops in Vienna, Heidelberg, Leipzig, and Dresden.

Of her experience tending poor patients at the dispensary, Anna noted: “The work was often thrilling, but mostly disappointing and depressing. Such a mass of dirty, irresponsible, non-responding people I met that I came to the conclusion that they were not ready for what we were able to give them. Crowded back tenements, dark broken stairs, no fire, with mother and children in bed to keep warm, street beggars with plenty in their tenement homes—these and more were the impossible situations I was constantly meeting. How dissatisfied it all made me.”

In addition to dissatisfaction, Anna must’ve felt driven to help, just as she was after her sister’s ordeal. This time, she would turn her sights to working to stop disease epidemics that disproportionately affected the poor and those in cramped living conditions.

With Mary’s assistance, Anna secured a position at the New York Department of Health’s brand-spanking new diagnostic laboratory in 1894. She began working on a project with lab director William Hallock Park. “They were an odd couple. He with an original and creative mind, but staid, even stolid, extremely precise and well-organized; she, wild, risk taking, intensely curious, a woman who took new inventions apart to see how they worked,” historian and author John M. Barry noted in his book about the 1918 influenza pandemic. “They complemented each other perfectly.”

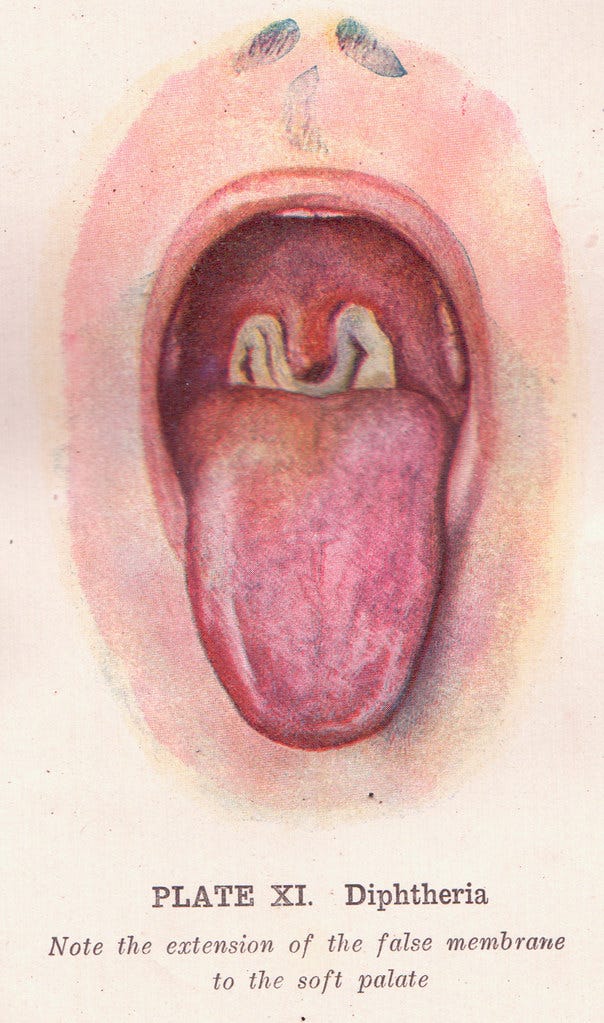

Their first project? Tackle the scourge that is diphtheria. In addition to fever, chills, tiredness, and a sore throat, the illness causes a thick, gray membrane to grow on your throat and tonsils, which can lead to difficulty breathing. The deadly disease came in waves: though on average it kills between 5-10 percent of those it infects (up to 20 percent in children), diphtheria epidemics saw death rates as high as 40 percent. Before it was known to be a “catching” illness, a 1700s epidemic in New England killed 2.5 percent of the population (30 percent of the children). In 1883, the diphtheria mortality rate in New York City was 125 per 100,000 people.

When Anna began working with Park “an epidemic was raging in a large institution for children. It broke out in the fall of 1894, a few weeks before we received our first antitoxin from Europe.” Park explained. “The danger to the children was so great that we decided to use the greater part of a small consignment of antitoxin which we at that time obtained from Germany.”

The bacterium that causes diphtheria had only just been identified in 1883; the strain Corynebacterium diphtheriae first cultivated a year later. The diphtheria antitoxin subsequently developed was used as treatment for the infected, not as a preventative vaccine. One of the earliest verifiable uses of diphtheria antitoxin in the United States was an ill 2-year-old in Cincinnati who was successfully treated with diphtheria antitoxin on October 16, 1894.

But this strain of the diphtheria bacillus was incredibly low-yield, making it both scarce and expensive. Enter Anna. In her first year at the lab, while Park was away on vacation, Anna isolated a strain of diphtheria bacillus capable of producing large quantities of antitoxin for a fraction of the cost. Working with a mild case of the tonsillar form of the disease, she had discovered a toxin 500 times as potent as the one currently available, which could be produced at one-tenth the price. Things worked quickly after that. Within a year, large amounts of the antitoxin was on its way to physicians across the United States and England, at no charge. Her reward was a promotion to full-time assistant bacteriologist.

Even though she made the discovery alone, laboratory directors were considered responsible for the work done under them. So the strain was dubbed “Park-Williams No. 8” after them both. Anna wasn’t one to chase glory, and as a woman in her position, likely wouldn’t dare complain. “I am happy to have the honor of having my name thus associated with Dr. Park,” she declared. Unfortunately, such a long name for a bacterium strain was cumbersome. More often than not, it was shortened to “Park 8.” The true discoverer, the woman, dropped off. Nearly forgotten.

What’s most impressive about such an incredible discovery is not that a woman made it, but the fact that it was discovered at all. Bacteriology had only been around since the late 1870s: The discovery of the anthrax bacterium in 1876 is considered the birth of modern bacteriology, as well as conclusive proof in this wild new theory that germs might cause disease, not miasmas or excess humors.

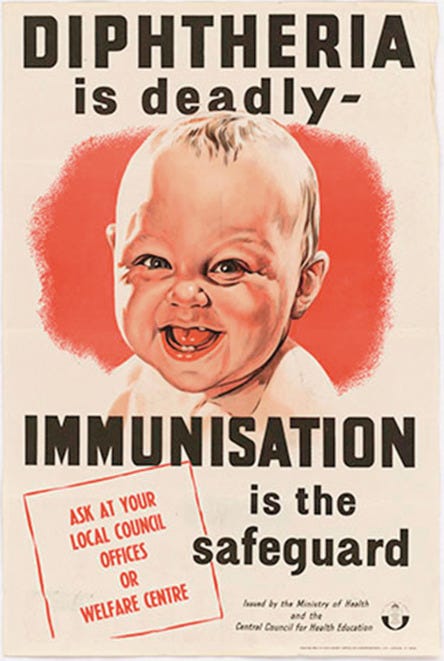

Eventually, Anna’s strain was used to develop a diphtheria vaccine. “Before the introduction of vaccines, diphtheria was a leading cause of childhood death around the world,” according to the CDC. “Due to the success of the U.S. immunization program, diphtheria is now nearly unheard of in the United States.”

Never one to rest on her laurels, in 1896 Anna went on sabbatical to hunt for a scarlet fever antitoxin at the venerable Pasteur Institute in France. Though she made no strides in that disease, she made quick progress with another. Participating in the Institute’s rabies research saw her continue it after returning to the U.S. By 1898, she had created an effective, mass-producible rabies vaccine. Still, those already infected with rabies were dying thanks to a diagnostic test that took 10 days. This would be Anna’s next problem to solve.

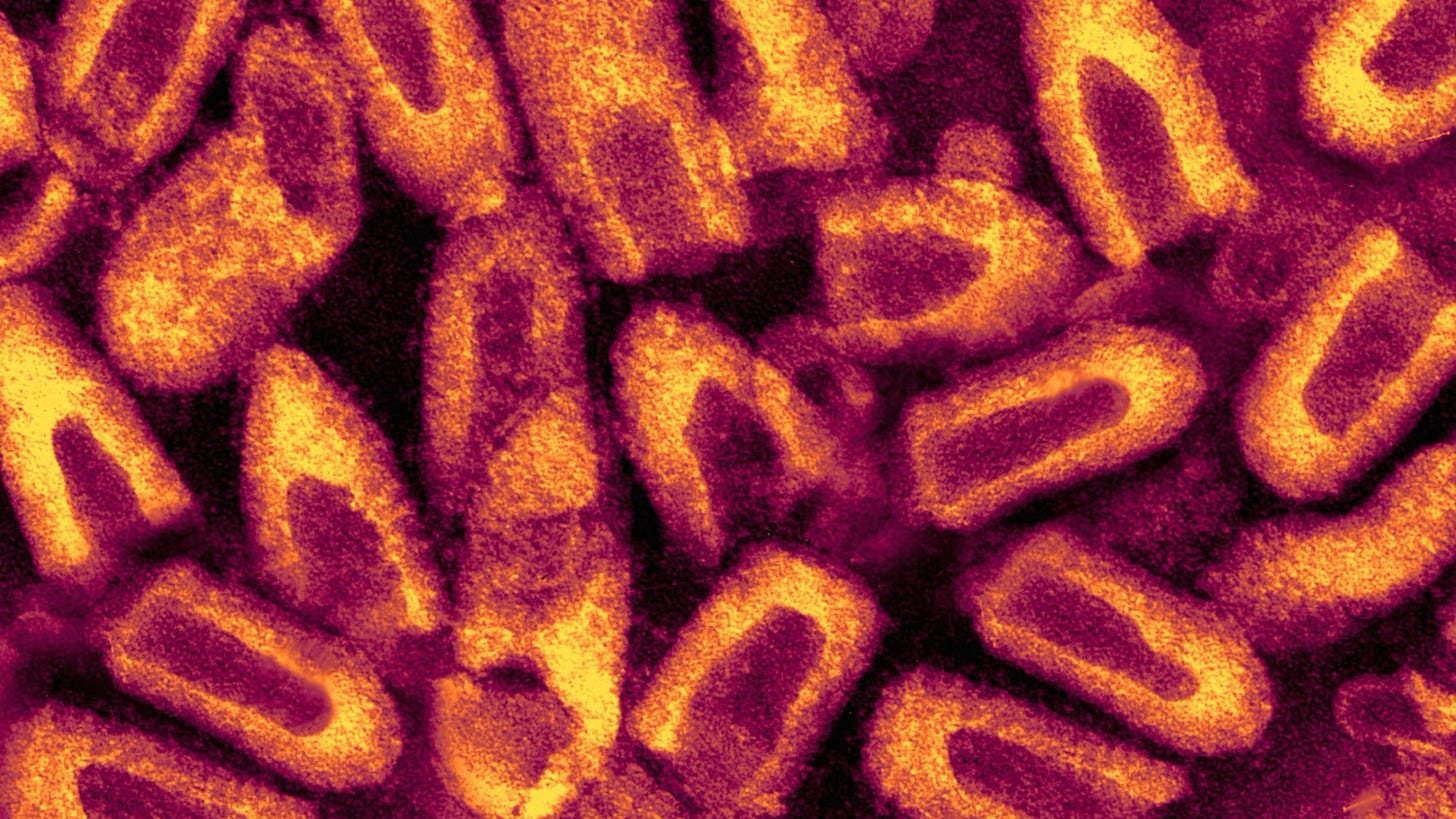

Her discovery of abnormal brain cells in rabid animals proved a diagnostic breakthrough. And yet another discovery for which she would receive little, if any, credit.

“She was not … to be generally recognized for this important stride forward, as she was not the first to publish a journal article about the brain cell abnormalities. At the same time that she was performing her research in New York, Adelchi Negri, an Italian pathologist, was studying the same phenomenon,” John S. Emrich writes in the American Association of Immunologists. “Although it is held that Williams was the first to recognize this distinct brain-cell structure in rabid animals, she is said to have ‘cautiously waited’ to publish her results. Meanwhile, Negri published his seminal paper in 1904 and became widely recognized for the breakthrough. The abnormal cells, known as Negri bodies, bear his name.”

Pressing on with making practical strides in speeding up diagnosis, Anna soon published a new method of staining the tissue to identify the Negri bodies. Her diagnostic test could give results in minutes.

Next, Anna and Park continued to battle disease together on the front lines of the Great Influenza pandemic of 1918.

Anna served as president of the Woman’s Medical Association, was elected to the American Association of Immunologists, and became the first woman elected chair of the American Public Health Association’s laboratory section. She also co-authored two books with Park: Pathogenic Micro-organisms Including Bacteria and Protozoa: A Practical Manual for Students, Physicians and Health Officers (1905) and Who’s Who among the Microbes (1929). The first was incredibly widely read among scientists, with 11 editions published by 1939. The second was one of the first biomedical books written for the general public.

In 1934 Anna and about 100 other city employees were forced into retirement by New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia. Even a popular petition organized by scientists and health professionals wasn’t enough to reverse her fate. At 71, she had just exceeded the mandatory retirement age of 70.

Anna never married, and had difficulty making friends. She thought resisting the urge to date and marry—“Detachment from all disturbing longings”—was vital to being a good physician. “I certainly had longings galore.” And she pondered “if it would be worthwhile to make friends and if so how I should go about it.”

Still, that didn’t stop her from pursuing adventures. “From my earliest memories, I was one of those who wanted to go places,” Anna declared. In her spare time, she traded the order and cleanliness of a laboratory for the risk and chaos of fast vehicles. She sought out frequent opportunities to be a passenger in pre-World War I airplanes piloted by stunt fliers and was a frequent recipient of speeding tickets, loving the thrill of zooming her car as fast as she fancied through the streets of New York City.

Further Reading:

“Anna Wessels Williams: Infectious Disease Pioneer and Public Health Advocate,”

by John S. Emrich. March/April 2012, pages 50–52, American Association of Immunologists: Women in Immunology/AAI Biosketch.

“Anna W. Williams,” by Jenny Stuart-Smith and Mike Cadogan. November 3, 2020, Life in the Fast Lane: Eponym.

“The First Century of Women in Vaccine Science: 1900-1930s (Part 1),” by Hilda Bastian. August 31, 2021. PLOS Blogs: Absolutely Maybe.

More about me:

Olivia Campbell is a journalist and author specializing in women, history, and science. Her first book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, was published March 2021 by HarperCollins/Park Row Books.

Buy a *signed* hardback copy online at Newtown Bookshop.

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page