A Trailblazer in Understanding Viruses, Cut Down By Nazi Anti-Semitism

Elisabeth Wollman's groundbreaking research on bacteriophages

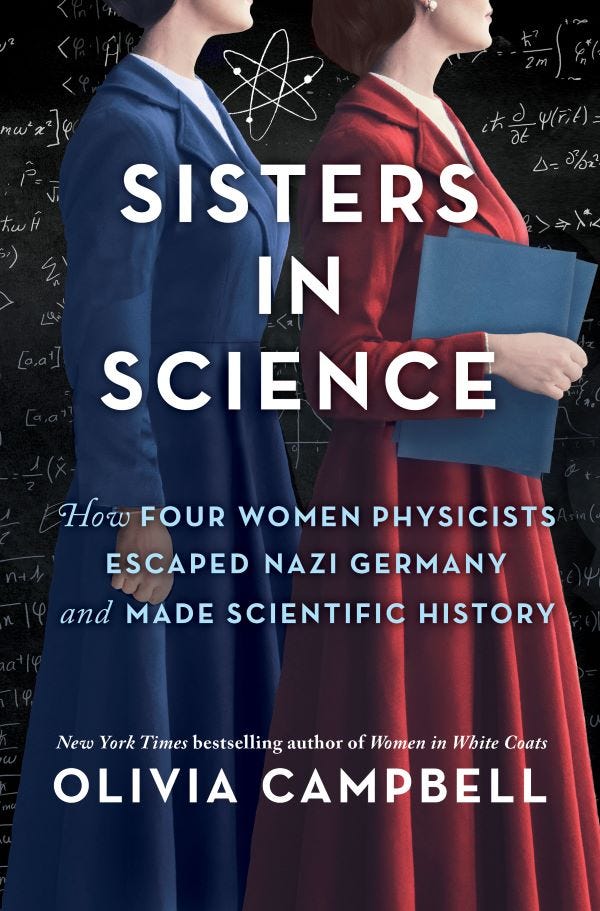

I mention Elisabeth and her husband in my forthcoming book on women scientists under the Nazis, but I wanted to give them the deeper dive I feel they deserve here in my newsletter.

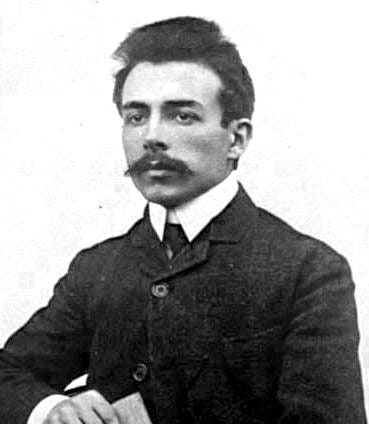

Born in Minsk, Russia in 1888, Elisabeth Michelis traveled to Belgium to attend university. Her mother gave her contact information for a family friend from Minsk who was also studying at the University of Liègeat, Eugène Wollman. She studied physics and mathematics, while he earned a doctorate in medicine in 1909. Eugène was awarded a scholarship for a research assistantship at the prestigious Pasteur Institute in Paris at the laboratory of Élie Metchnikoff, a fellow Russian who had just won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his immunology research.

Eugène was hopeful Elisabeth would follow him again.

“From her letters from that period, it is clear that she had many suitors, and one of them was Eugène. After he moved to Paris and she was still studying in Belgium, he pleaded with her to join him there, obviously intending to marry her. Eventually, she agreed. Both families were not religious but were immersed in the Jewish community, and the two were married in 1910 in a Jewish wedding,” their grandson, Francis-André Wollman, explained.

Elisabeth began “working” at the institute as a voluntary assistant in the laboratory of chemist Jacques Duclaux, whose research focused on colloids (mixtures of materials that won’t fully mix). She also continued her studies at the Sorbonne University, narrowing her professional specialization to physical chemistry.

Eugène and Metchnikoff’s research focused at first on microbes that decompose starch in the small intestine, as well as on the sterile breeding of flies, tadpoles, and guinea pigs for use as lab animals. They were successful in creating the first germ-free blow flies by treating the egg surface with diluted hydrogen peroxide and raising the larvae on sterilized meat.

Elisabeth was also involved in this work. In 1912, she published an article with Metchnikoff on sterilization methods; 1915 saw the publication of the Wollmans’ first joint article, on sterile animals and their consumption of bacteria found in barnacle food. This solidified the pair as a scientific power couple to be reckoned with.

Before long, Eugène was promoted to head of his own lab, allowing Elisabeth to fully focus on collaborating with him, still on an unpaid basis. Sexism and the social expectation of married women not working (especially if the husband had a good job) meant she was not considered for a paying position.

The Wollmans’ work focused on bacteriophages, specifically, lysogeny, which is the viral reproduction cycle in which a bacteriophage's genetic material integrates into a host bacterium’s DNA. They were the first to make the groundbreaking assertion that lysogeny resulted from a viral attack on bacteria. The couple published many notable joint and individual articles.

While Elisabeth might not have been seen as important enough to pay, her colleagues certainly saw how noteworthy her contributions were.

“Everyone in Eugène Wollman’s laboratory recognized the important role she played there. She not only conducted experiments and meticulously analyzed their results, but was also involved in experiment planning, raising scientific hypotheses, and skillfully guided her husband's sometimes fiery approach towards constructive compromises,” institute director Pierre Mercier explained.

But a fruitful professional collaboration wasn’t all the Wollmans were birthing. During this time, they also had three children, Alice, Elie, and Nadine, who would all go into scientific careers.

“She wasn't merely a technician or assistant in his laboratory; she was a full partner in their work,” their grandson noted.

The Wollmans were trailblazers in molecular genetics. Their fruitful, decades-long collaboration built the foundation that would allow future scientists to understand the nature of viruses, cancer, and HIV.

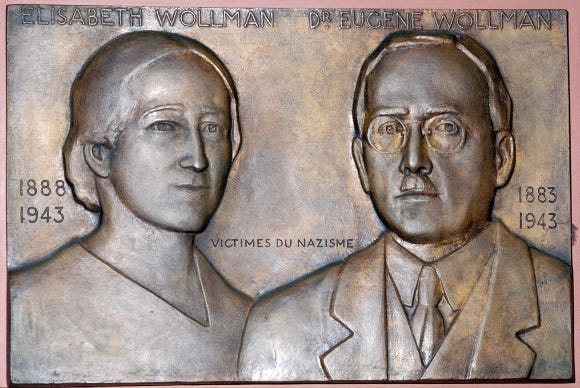

But the Wollmans were also Jewish. They managed to work relatively normally for a few years under Nazi occupation, but soon, ever-restrictive racial laws encroached on their professional and personal lives. As Jews, they were no longer allowed to publish their research findings.

In March 1943, French police came to the institute to arrest Eugène. The director instructed him to hide in the institute’s hospital and told the police he had been hospitalized. From then on, Eugène was forced to live in the hospital, only occasionally sneaking out to his apartment to visit his family on weekends. Living there at the time were Elisabeth, their daughter Nadine, and her husband.

That December, police raided their apartment. Police arrested everyone except Nadine’s husband, who wasn’t Jewish. Elisabeth, Eugène, and Nadine were imprisoned. Luckily for Nadine, she and her husband had been working in Irène Curie and Frédéric Joliot-Curie’s lab; the renowned scientists were able to negotiate her release.

The Wollmans’ son, Élie (named after Eugène’s mentor) was an active member of the French Resistance. He was unsuccessful in his attempts to get his parents released. From the Drancy detention camp, Elisabeth and Eugène were deported to the Auschwitz death camp in a group of 900. They were among those sent to the gas chamber upon arrival. Two scientific geniuses—lost to anti-Semitism.

After the war, Élie and one of the Wollmans’ research students continued the couple’s research project on bacteriophage lysogeny (picking up where their unpublished manuscript left off), culminating in a Nobel Prize.

Further Reading

Embryo Project Encyclopedia: Elisabeth Wollman, Arizona State University.

Kostyrka, Gladys; Sankaran, Neeraja. "From obstacle to lynchpin: the evolution of the role of bacteriophage lysogeny in defining and understanding viruses.” Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science. December 2020.

To learn more about bacteriophages, preorder Lina Zeldovich’s book, The Living Medicine: How a Lifesaving Cure Was Nearly Lost―and Why It Will Rescue Us When Antibiotics Fail, out October 22, 2024.

Goodreads Giveaway!

Win a copy of my forthcoming book, Sisters in Science: How Four Women Physicists Escaped Nazi Germany and Made Scientific History, in this Goodreads Giveaway! 10 hard copies are up for grabs; ends October 15.

More About Me

Olivia Campbell is the New York Times bestselling author of Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine and the forthcoming Sisters in Science: How Four Women Physicists Escaped Nazi Germany and Made Scientific History.

She is a thesis advisor for her alma mater, Johns Hopkins University's science writing program, and a freelance editor at Parents magazine and Everyday Health. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, The Atlantic, The Guardian, Washington Post, New York Magazine, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, and History.com, among others. She lives outside Philadelphia with her husband, sons, and cats.

Find out more on her website.

Excellent. Thank you. I can’t wait to read your book.