A "Wonder Woman" of Many Talents

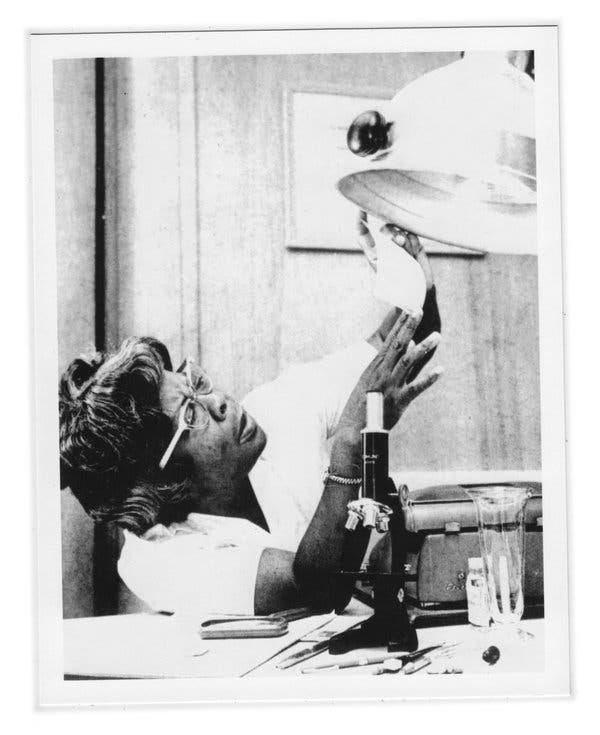

Bessie Blount shows the world that Black women can be brilliant inventors.

Physiotherapist, forensic handwriting expert, and brilliant inventor, Bessie Blount did a little bit of everything. Throughout all of the incredible, varied work she undertook, Bessie’s mission in life was to show the world “that a black woman can invent something for the benefit of humankind.” Because of all the rejection she endured, all of the doors slammed unceremoniously in her face, Bessie got good at singing her own praises over the years. But it was never meant for her own personal benefit.

“Forget me. It's what we as a race have contributed to humanity — that as a black female we can do more than nurse their babies and clean their toilets,” 93-year-old Bessie told The Virginian-Pilot newspaper in a 2008 interview. She was speaking up for Black women everywhere.

Bessie was born in Hickory, Virginia in 1914. As a child, she attended the same one-room school that her mother had, Diggs Chapel Elementary School. The school had been established after the Civil War to educate black and Native American children. Her teacher was known to rap her knuckles as punishment for writing with her left hand. Bessie’s response was to teach herself how to write with her right hand, with her feet, and with her mouth. Sixth grade was as far as she could go, educationally, as a Black girl in Chesapeake, Virginia. She cobbled together a further education as best she could. After her father died, she and her mother moved to New Jersey.

She worked long and hard to qualify for entry into Union Junior College. Nurse training followed, at Community Kennedy Memorial Hospital. It was the only hospital in the state owned and operated by Black people. After some postgrad classes at Panzer College of Physical Education and Hygiene, Bessie became a physiotherapist. Her first position was at Bronx Hospital in New York.

After America entered the second World War, Bessie dedicated her talents to volunteering. The Red Cross’s “Gray Ladies” were supposed to merely perform hospitality services, nothing too highly skilled or medical. But Bessie and the other ladies at the New York metro area Base 81 ended up providing services like psychiatry and occupational therapy to the many injured veterans.

The hospitals were overwhelmed with servicemen who’d had their upper limbs amputated or whose injuries had left them paralyzed. Bessie taught these men what she’d taught herself as a girl: to write with things other than your hands. She showed them how to use their feet and their teeth to write, taught them to read Braille using their toes.

“After coming in contact with paralyzed cases known as diplegia and quadriplegia (blind paralysis), I decided to make this my life’s work,” she told the Afro-American newspaper in a 1948 interview. Bessie learned how to draw by her work posing for medical sketches and photos. “This enabled me to design many devices for handicapped persons,” she explained.

Bessie soon heard about how the army had been trying to create a self-feeding device for veterans who’d lost their arms or the use of their arms. All of the army’s attempts so far had been unsuccessful. This was just the sort of challenge Bessie needed. Bessie’s kitchen transformed into an inventor’s workshop. First, she spent nearly a year designing the device. Then, she spent a further four years, and $3,000, to build it. “I usually worked from 1 a.m. to 4 a.m.,” she told the Afro-American.

Finally, her creation was realized: a self-feeding device that delivered a mouthful of food via a spoon-shaped tube. To dispense the food, you just had to bite down on a switch. It shut off automatically. She also designed a food receptacle support that affixed to your neck to hold a dish or cup. For her “Portable Receptacle Support,” she received a U.S. patent in April 1951, three years after filing for one. That year, she also married Thomas Griffin. They went on to have one son.

Bessie excitedly demonstrated her device to the Veterans Administration, asking $100,000 for the rights, but they showed little interest. Still convinced of how impactful her inventions could be, she became the first woman and the first Black person to appear on “The Big Idea.” It was a 1950s TV show where people presented their inventions. The press hailed her life-changing device, dubbing her “The Wonder Woman.” Still, no one in America expressed interest in purchasing the invention. So Bessie turned the rights to her idea over to the French military, for free. It has improved the quality of life for countless disabled people.

Counted as one of Bessie’s closest friends was Theodore Edison, son of Thomas Edison. They’d struck up a friendship after Bessie served as a physical therapist to his mother-in-law. He was a trained physicist who’d started his own research lab. The two shared a love of invention. Bessie and Theodore discussed all of the many extraordinary ideas that bloomed in their minds. It was in his home in West Orange, New Jersey, that she invented a disposable version of the emesis basin. Hers was molded out of newspaper, flour, and water, then baked. The Veterans Administration again waved Bessie and her ideas away. She was off to Europe again, this time to sell the basin design to Belgium. To this day, its hospitals use a version of her design.

Bessie’s interest in handwriting then took a forensic turn. Bessie believed that a person’s handwriting could tell you everything you needed to know about them, including their mental and physical health. There was a science to it, yes, but Bessie also had an incredible gift for reading between the lines of a person’s handwriting. “Bessie bristles at the slightest suggestion that her handwriting analyses are the scribblings of a self-styled seer rather than scientific revelations,” noted a September 1958 story in the Philadelphia Tribune. She began consulting for law enforcement agencies.

Bessie’s 1968 scientific paper “Medical Graphology” discussed the trait stroke theory that every stroke of the pen corresponds to a different personality trait. Handwriting analysis was seen as a sort of pseudoscience at the time, but Bessie hoped to change this reputation. “I have been taught that a person’s signature is his ‘written’ fingerprints and are just as valid as those on his fingers or the sole prints of his feet,” she wrote in 1970. Soon, she was accepted into an advanced training course at Scotland Yard in London; the first Black woman to undertake the course. The nickname her British colleagues coined for her, Mama Bessie, stuck. It became her preferred name for the rest of her life.

Upon her return to the states, she applied for a job with the FBI. But she didn’t get it. So she expanded her consulting agency to include verifying the authenticity of documents related to slavery, the Civil War, and Native American treaties with the United States, working on embezzlement and forgery cases. At the Vineland, NJ Police Department she consulted on cases, trained officers in handwriting analysis, and testified in court. What’s more, she became a founding member of the American Association of Handwriting Analysts.

“Bessie Blount is a remarkable woman. She is a vital speaker, one who has the enthusiasm and remarkable accomplishments to hold her audience,” noted M. N. Bunker, founder of The American Institute of Grapho-Analysis. Bunker was notoriously hard to impress.

Bessie continued to consult on cases into her 90s. She also loved to take the models of her inventions on lecture tours to schools. When asked to donate her inventions to African American museums, Bessie would reply ‘Does science have a color?’

Further Reading:

“The Woman Who Made a Device to Help Disabled Veterans Feed Themselves—and Gave It Away for Free,” by Leila McNeill, Smithsonian Magazine, October 17, 2018.

“Overlooked No More: Bessie Blount, Nurse, Wartime Inventor and Handwriting Expert,” by Amisha Padnani, The New York Times, March 27, 2019.

“Bessie Blount Griffin: A Black Woman's Journey to Pioneering Forensic Scientist,” by Elena Ferrarin, A&E Real Crime, March 9, 2021.

More about me:

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page

Order my book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, out March 2, 2021 from HarperCollins/Park Row Books.

Buy a *signed* hardback copy online at Newtown Bookshop.