We don’t know much about the life of English astrologer Sarah Jinner, when she was born, when she died. What we do know is that she lived in London and published three almanacs between 1658 and 1664. These texts were positively brimming with health and wellness advice that reflected a desire to preserve and share knowledge that could improve women’s health—and their sex lives.

Sarah’s main goal? To educate women on how to treat gynecological ailments at home, to help them take control of reproduction by showing them how to keep track of their menstrual cycles, and to improve their sexual health: “that our Sex may be furnished with knowledge: if they knew better, they would do better,” Sarah wrote. “Better” being more satisfying sex.

Improper care of one’s genitals, she feared, was one of the main obstacles to good sex. A visit to the doctor for gynecological complaints would invariably lead to a diagnosis of too much sex or not enough, so women often preferred to keep such ailments to themselves.

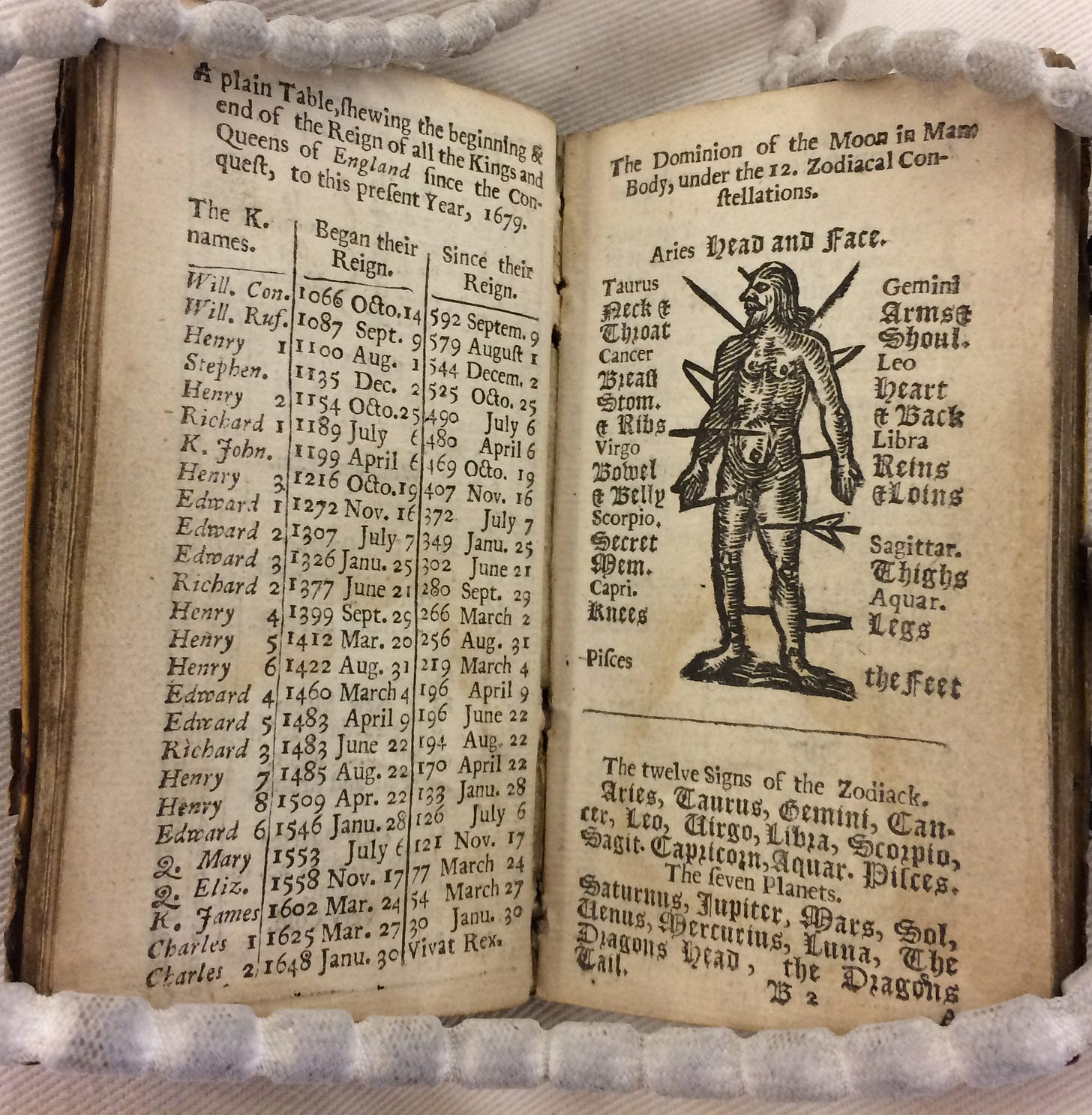

Almanacs were incredibly popular in early modern Europe. They were small booklets that included predictions for the coming year, medical advice, meteorological information, tides tables, and other encyclopedic information. Often, they included anatomical diagrams of the zodiacal man. The golden era of almanacs in England spanned 1550 to 1700, with a special boost in popularity in the second half of the 1600s.

Sarah’s almanacs are unique in that they are authored by a woman, and she is often thought of as one of the first women in England to make a living writing. Proving true women’s authorship of early modern texts can be tricky since several cases of men using female pseudonyms have been uncovered. In Sarah’s case, we have at least one form of proof: Army captain Henry Herbert is noted to have mentioned in 1673 that there was a well-known astrologer practicing in London by the name of Sarah Jinner.

In her almanacs, Sarah offers up recipes for aphrodisiacs, and remedies for infertility, gynecological illnesses, and incontinence. She outlines the best times to engage in sexual activity, and when to refrain from it. Knowledge of ovulation and its role in conception was still a long way off, so Sarah’s advice for good or bad times to conceive were based on astrology.

Period sex would create deformed infants; sex anytime in July was ill-advised. Some of her sex advice was extremely date-specific. September 12, 1658: “Venus being in Scorpio, I fear that the naughty wantons of our sex … will be peppered with the pox.” The total solar eclipse of November 14, 1659 would bring with it amorousness: “many Ladies that had been besieged by suitors [will] … surrender.”

Recipes for contraceptives and abortifacients were particularly sought after. During this era when Hippocrates’s humoral theory still dominated medicine, a woman’s period was seen as a necessary monthly balancing of the humors. So for a while, there wasn’t a great deal of stigma attached to taking an herbal remedy aimed at “returning the menses” if your period had stopped.

Sarah is credited with the important work of making a point to preserve classical knowledge of abortifacients in her texts. Male-authored medical compendiums of the time were beginning to exclude such knowledge as it was becoming increasingly controversial. She suggests pennyroyal and mugwort to help remove the obstruction hindering your normal period. Removing obstructions or blockages was common terminology in humoral medicine. Many medicines or treatments were created to purge whatever was preventing normal flow or functioning.

In addition to medical advice and guidance on sexual health, Sarah’s almanacs make specific weather and agricultural predictions, tracks the lunar cycles, and calculates the position of the planets.

“Having Venus in the twelfth house in opposition to Jupiter in the first house, and the Moon in the seventh in Scorpio, doth foretell many diseases in women. … Mercury in the ninth house puts you a jogging to see your friends, and delight in discourse, as gossipings.”

Prophecy was a potentially deadly activity for women in England at the time. In 1534, Elizabeth Barton had been executed for predicting the fall of Henry VIII. Then again, perhaps it wasn’t prophecy, but merely crossing King Henry that could get you killed. Still, several other lady prophets who dared to discuss politics in their writings endured public whippings, beatings, and burnings. Sarah made sure to keep her more political prognostications vague: March 1659, she predicts trouble with Spain.

Another potential problem with dabbling in prophecy was that you could easily be branded a witch. Sarah tried to ensure she was not accused of witchcraft by providing a cure for being bewitched. She also had to deal with poor imitators. In 1659, a pornographic version of her 1658 almanac was published.

After examining the impending eclipses, Sarah forebodingly warned that 1659 would bring with it an “increase and discovery of Witches and Fortune Tellers.” She also tried to distance herself from the more ecstatic women prophets of the era. “Novice lay pulpetiers begin more and more to decline their impudent and audacious publike babblings,” Sarah wrote with exasperation.

Astrology was seen as a legitimate science at the time, practiced by eminent scientists and scholars, and Sarah used this fact to try and gain a certain level of credibility and legitimacy for her predictions and medical advice.

“Although we are accustomed to think of modern astrology as closely allied with mysticism and secret knowledge, Jinner’s … work falls within the intellectual traditions which would develop into the modern scientific method, with its emphasis on unvarying mathematical law, repeatability, and mathematical demonstration,” explained medical historian Alan S. Weber.

In her almanacs, Sarah also takes the opportunity to fight back against men’s proclamations of women’s inferiority. To Aristotle’s assessment that women are just imperfect men, she argues that world leaders like Elizabeth I do not appear to be mere imperfect copies of men. She names several notable women poets, philosophers, and physicians as evidence of women’s equality. Women’s intellectual, philosophical, and medical talents were just as robust as men’s, if not in some cases, more so, she asserted.

Sarah’s “note to the reader” in her 1658 almanac:

“You may wonder to see one of our Sex in print especially in the Celestial Sciences: … But, why not Women write, I pray? have they not souls as well as men … Mankind is preserved by woman: many other rare benefits the world reapeth by women, although it is the policy of men, to keep us from education and schooling, wherein we might give testimony of our parts by improvement: we have as good judgement and memory, and I am sure as good fancy as men, if not better. … When, or what Commonwealth was ever better governed than this by the vertuous Queen Elizabeth? I fear me I shall never see the like again, most of your Princes now a dayes, are like Dunces in comparison of her: either they have not the wit, or the honesty that she had. … Why should we suffer our parts to rust? Let us scowre the rust off, by ingenious endeavouring the attaining higher accomplishments.”

Would that all women had such audacity!

More about me:

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page

Pre-order my book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, out March 2, 2021 from HarperCollins/Park Row Books.