Dr. Hamilton: Traveling Physician, “Female” Husband

Considering quack doctors and trans history in Georgian England through the case of Charles Hamilton

Mary Hamilton was born in Somerset, England sometime around 1724. The family then moved to Angus, Scotland. It was here that Mary began dressing in her brother’s clothing. At age 14, Hamilton, dressed as a boy, traveled to Northumberland and began apprenticing under Dr. Edward Green. Hamilton rotated through various new names: Charles, James, George, before appearing to finally settle upon the moniker Charles.

Hamilton would’ve helped Green gather ingredients and supplies, and mix up and sell medicines. He also would’ve learned how to advertise their medical services, examine and diagnose patients, and sell their curatives.

Dr. Green billed himself as an “operator and oculist” able to cure a miraculous host of ailments: scurvy, leprosy, eye diseases, dropsy—even cancer. But he was actually a “noted mountebank,” aka quack doctor. Now, I know that quacks are understood to be money-grubbing frauds who knowingly fleece the masses by selling useless nostrums and false hope, but in the Georgian era, medicine wasn’t nearly so black-and-white.

“If the mark of the beast setting quacks apart from proper practitioners is either fraudulence, or incompetence, the demarcation dissolves in confusion. Many of those called quacks were, in their various ways, well-intentioned and skilful. In any case, the Georgian regulars were not exactly spotless in these respects,” eminent medical historian Roy Porter wrote in History Today. We cannot, as historians, simply cordon off the quacks as cheats and bunglers.”

In other words, some of the “regular” physicians could be just as inept or profiteering as some quacks; and some quacks could be just as honest and knowledgeable as some regular physicians. Medical degrees could be purchased, after all, from some universities who were just as in it for the money as the docs were. Quack or regular, the fact is that at the time, so little was known of how the body actually worked and so many purportedly therapeutic medicines and treatments actually did more harm than good (often slowly poisoning patients).

While there was a hierarchy to Georgian medicine—with university-educated physicians and apprenticed surgeons and apothecaries enjoying the top rung—healthcare was delivered by a vast tapestry of practitioners. For one thing, wives and eldest daughters were expected to know how to mix and administer a few basic medicines for their households, and to treat their extended family members. Some wealthier wives were expected to treat their whole community. Depending on your ailment and gender, you might visit a midwife, wise woman, chemist, or yes, even a traveling quack doctor at some point in your life.

Beyond the safety of London’s licensing and medical register lay a wild west of British healthcare. Trustworthy practitioners of all stripes had to be vetted by word-of-mouth reference and personal experience alone. And of course, the placebo effect has always been a thing.

It said a lot about Dr. Green’s reputation, then, that Poor Law administrators had hired him to treat indigent patients. They paid him two guineas per case to treat all manner of ailments, including fistulas. After about three years of training with Green, Hamilton spent an additional year under the tutelage of Dr. Finley Green. Four years of training under ostensibly decent medical practitioners seems downright comprehensive for a physician at the time.

In 1746, Charles Hamilton moved to Wells, Somerset, excited to finally set up a medical practice all his own, to enjoy his independence and support himself. He rented a room at the boarding house of Mary Creed. She was a widow who made ends meet by renting out rooms in her house. Ms. Creed’s niece Mary Price also lived in the home.

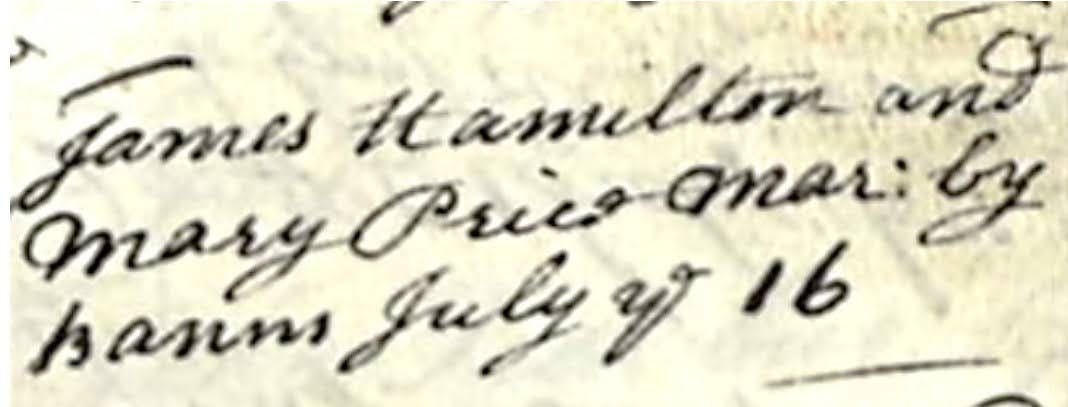

Hamilton and Price apparently fell head-over-heels in love very quickly, as they were married that summer, on July 16, 1746. For the next two months they traveled through Somerset as husband and wife selling quack remedies.

By September, Charles’ world came crashing down. While the couple was in Glastonbury, Mary claims she confronted Charles about her suspicions that he had been assigned female at birth. When Charles readily admitted to this, Mary reported him to the authorities. He was arrested on September 13.

Once the press caught wind of this salacious case, they couldn’t get enough. Charles was a veritable media sensation. “There are great numbers of people flock to see her in Bridewell, to whom she sells a great deal of her quackery; and appears very bold and impudent,” the Bath Journal reported on September 22, shortly after Charles’ arrest. “She seems very gay, with Periwig, Ruffles and Breeches; and it is publicly talked that she has deceived several of the fair sex by marrying them.”

Charles was charged with fraud and brought before the court with very little wait. Mary Price testified that “after their marriage they lay together several nights and … Charles … entered her body several times which made her believe Hamilton was a real man.”

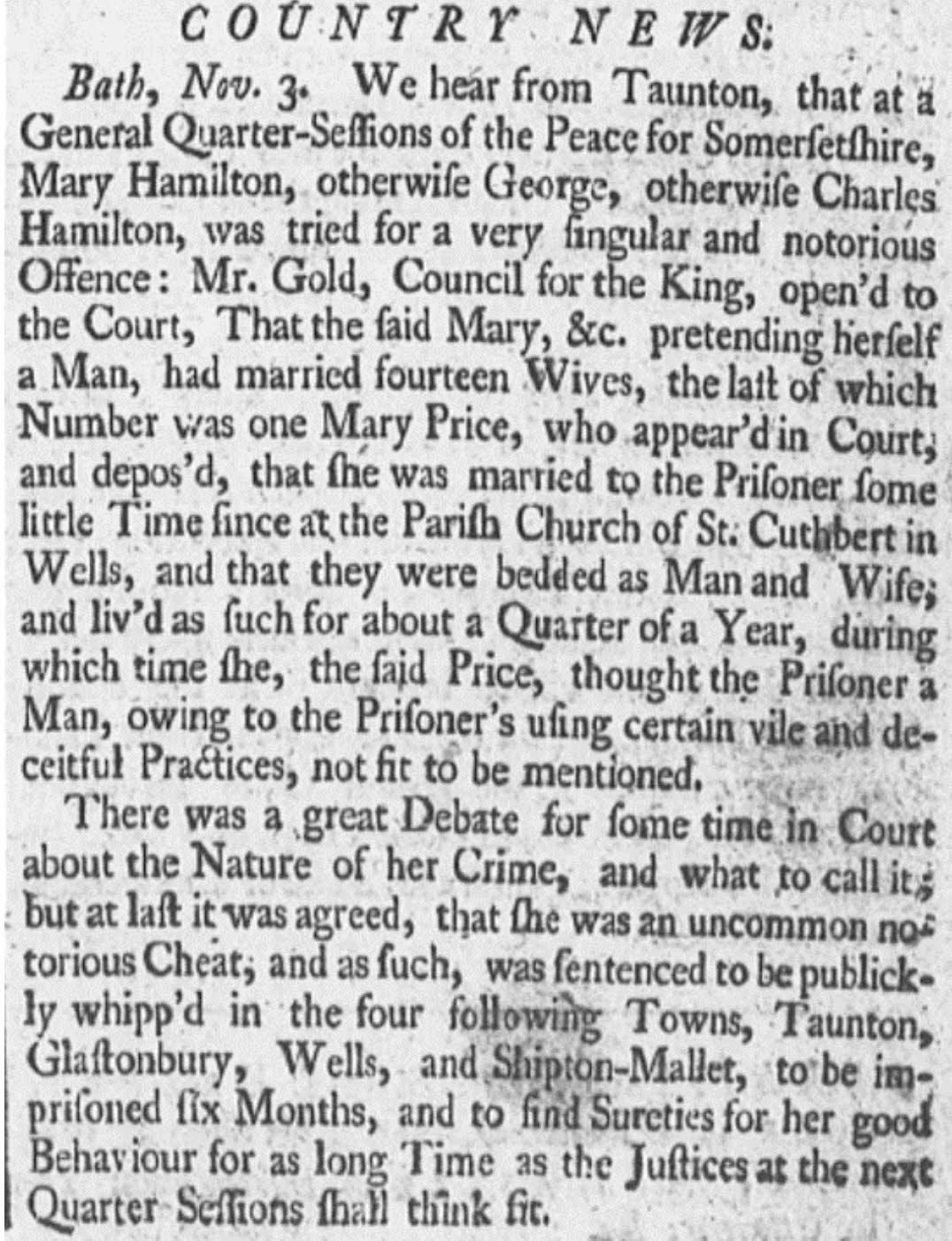

The verdict, presented on October 7, was that Hamilton was “an uncommon, notorious cheat” and would be sentenced to six months imprisonment, during which time they would be stripped to the waist and publicly whipped four different times in four different towns, at three-week intervals until Christmas 1746.

Again, the Bath Journal is on it with the particulars of the case:

“We hear that … Mary Hamilton, otherwise George, otherwise Charles Hamilton, was tried for a very singular and notorious Offence: Mr Gold, Counsel for the King, opened to the court that the said Mary, pretending to be a man, had married 14 wives, the last of which number was one Mary Price, who appeared in court and deposed that she was married to the prisoner some little time since at the parish church of St. Cuthbert in Wells, and that they were bedded as man and wife, and lived as such for about a quarter of a year, during which time, she, the said Price, thought the prisoner a man, owing to the prisoner using certain vile and deceitful practices, not fit to be mentioned. There was a great debate for some time in court about the nature of her crime, and what to call it, but at last it was agreed that she was an uncommon, notorious Cheat, and as such was sentenced to be publicly whipped in the following four towns: Taunton, Glastonbury, Wells and Shepton Mallet, and to be imprisoned for six months.” - November 3, 1746.

While the claim of 13 previous wives was never substantiated, Hamilton was actually convicted of “vagrancy” because of the vague nature of the laws pertaining to such crimes. The truth was that the court wanted to see Hamilton punished, but that there was no precedent for defining exactly what it was they objected to so vehemently. It wasn’t that Hamilton presented himself as a man that they found disdainful, it was that he had apparently sexually deceived a woman. Now, whether or not Mary had truly been unaware of Charles’ gender at birth, or whether she was just looking for a way out of the marriage is up for debate. Charles was actually imprisoned with other men, specifically with men charged with similar issues pertaining to relationships: clashes with wives or lovers, bastardy, lack of child support.

Charles was certainly not the only trans man enjoying a relationship with a woman in the Georgian era, but because of the court case, his story has become one of the most well known. The story soon came to the attention of the novelist Henry Fielding, who anonymously published The Female Husband on November 12, 1746. An overtly titillating interpretation to say the least, the text is known to be “one part fact, ten parts fiction.”

Scholars have recently tracked Hamilton’s trail and believe that once he was released from prison, he spent autumn 1751 to January 1752 on a ship bound for North America. After landing in North Carolina, he apparently traveled around Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware before settling in Chester County, Pennsylvania. “Charles Hamilton” makes a couple of appearances in local newspapers—once for allegedly stealing a horse—which note that he “pretends to be a doctor” and is “small built” with “very full eyes.”

Trans people have always existed and will continue to exist. I was dismayed to find that trans people have also always potentially faced violence and intolerance simply for being themselves. If Charles Hamilton really lied to potential partners that’s not something to condone, but it’s also not something you can really blame him for, either, especially given the result of being “found out.” Not to mention that public whipping is a far harsher crime than he deserved for lying. Many trans people in history have lived happy lives with partners: solid relationships presumably built on truth and mutual understanding.

Applying a modern gender lens to historical figures is always tricky. At various times in history, and throughout various cultures, gender has been more loosely or more strictly defined. I always hope I refer to historical figures by their preferred gender; by what they would’ve referred to themselves as. I tend to go by the rule that if a person presented themselves as one gender, then that’s likely what they wanted to be referred to as.

In some lucky cases, we have diaries or letters where people refer to their own gender. This, of course, is the best way to know what they would’ve wanted. In this piece, I have referred to Charles Hamilton as “he/him” because that’s how he lived his life. Whether or not he would’ve used “they/them” pronouns had they been an option at the time, we can never know. I can only hope I have done his story justice.

Further Reading:

Roy Porter, “Quack Medicine in Georgian England,” History Today, Volume 36, Issue 11, November 1986.

Jen Manion, Female Husbands: A Trans History. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Sheridan Baker, “Henry Fielding’s the Female Husband: Fact and Fiction.” PMLA, Volume 74, No. 3, 1959, pp. 213–24.

More About Me:

Olivia Campbell is the author of the New York Times Bestseller Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine. Her essays and journalism have appeared in The Atlantic, The Guardian, Washington Post, New York Magazine/The Cut, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, HISTORY, Catapult, and Literary Hub, among others. She lives outside Philadelphia with her husband, three sons, and two cats.

Order her book here, or snag a *signed* hardback copy online at Newtown Bookshop.

Amazon Author page