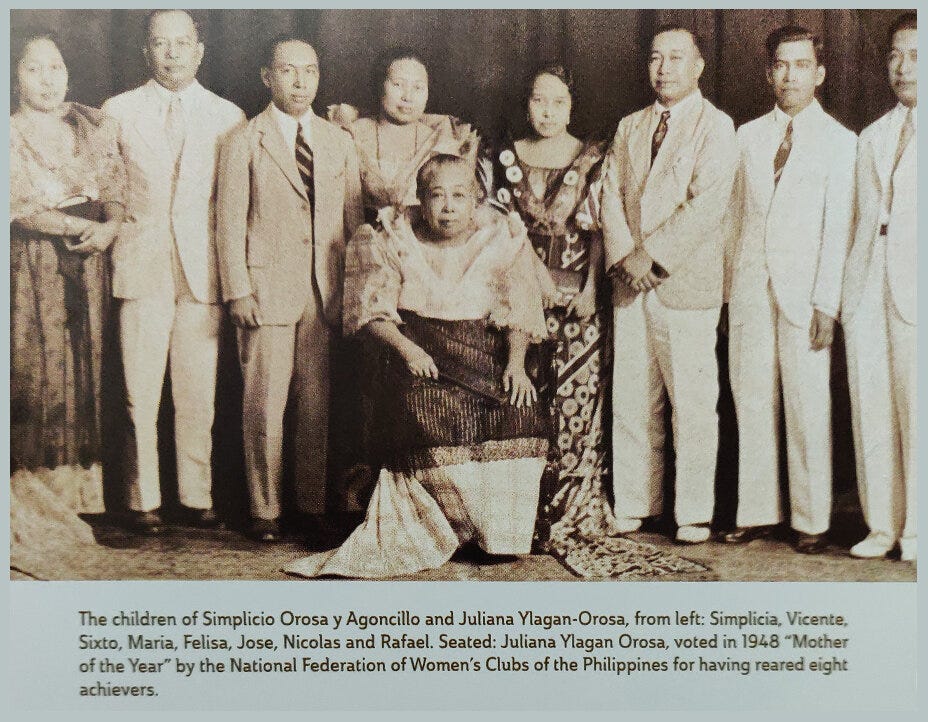

It may sound odd, but World War II was when pharmaceutical chemist María Orosa’s talents really shone. But María was head of the Philippines’ Division of Home Economics, where she specialized in food preservation. She immediately recognized how important her work could be to ensuring the food security of soldiers and civilians alike. The rest of her family evacuated (her seven siblings had also become successful, prominent citizens), but María stayed behind.

“I will continue working and serving my people,” María is remembered saying.

Her beloved country’s agricultural production and food importation had been severely impacted by the war, so she dedicated herself to ensuring no one went hungry or got sick from vitamin deficiencies. María’s ingenuity in repurposing valuable food waste led to the creation of Darak, a flour made from the typically discarded rice bran that was packed with vitamins A, E, D, and B. She also created Soyalac, a protein-rich powdered soy milk. She developed and disseminated recipes that utilized these and other local ingredients to help keep the civilian population fed. Her Tiki-Tiki cookies, made with Darak, became a cherished culinary staple.

When María was made a captain in Marcos “Marking” Augustín’s resistance fighting group, Marking's Guerrillas, she set about hiring carpenters to hollow out bamboo so that Soyalac and Darak could be smuggled to civilians being held prisoner and guerrilla fighters and U.S. soldiers being held as prisoners of war by the Japanese at several sites across the country. Without the supplementation, many of these prisoners would’ve died of starvation. Using money from her own pocket, María made up nutrient-dense rations for the resistance fighters.

She had patriotism and anti-colonialism in her blood. Her father was involved in resistance movements against both Spain and America’s colonization attempts. The Americans even briefly held him as a political prisoner. The war was just the latest way María had applied her science smarts to helping her people not only survive, but thrive.

María Ylagan Orosa was born on November 29, 1892 in Taal, Batangas. She studied pharmacy at the University of the Philippines. In 1916, at the age of 23, she became a government scholar and traveled to the US to enroll at the University of Seattle.

While at school, she lived at a YMCA and worked several odd jobs. She was a household helper, and sold wares to department stores that her mother made and shipped to her, such as baby bibs, nightgowns, embroidery, handkerchiefs, hats, and slips; in the summers, she worked at a salmon cannery in Ketchikan, Alaska. In addition to earning $80 a week, working at the cannery helped María learn more about food preservation techniques. She sent the money made from her mother’s goods back home.

She went on to earn THREE bachelor of science degrees: pharmaceutical chemistry in 1917, food chemistry in 1918, and pharmacy in 1920. The following year, she completed her master’s degree in pharmacy.

In 1918, while still working toward her two pharmacy degrees, the dean of the College of Pharmacy offered María the role of assistant at his Food Laboratory, which she happily accepted.

“The reasons for accepting are first, it is a very decent position and secondly, it is an honor. Here in America, it is very difficult to obtain the kind of job I have just been offered and accepted. Before they offer to a person of color, such as Filipino, Japanese or Chinese, the jobs are first offered to whites. So, I am indebted to Dean Johnson, that although I am a person of color, he offered me the job ahead of everyone else,” María wrote to her mother.

The dean was also Washington’s state chemist, so in the lab, María got to inspect samples of lemon, ginger, and vanilla extracts, and foods like milk, eggs, and sugar.

“My job is to experiment with and test the products brought by the Food Inspectors for purity, adulteration or dilution, and minimum standards,” María wrote. “My work is a great responsibility plus a large help to me in my studies. The salary is generous.” She earned $100 a month.

Refusing an offer to become a chemist for the state of Washington, María returned home to the Philippines in 1922, and soon began working for the Bureau of Sciences. She focused on reviving indigenous foods that had been unfairly maligned by colonizers. María flour from cassava, vinegar from pineapples, jelly from guava, wine from native fruits, agar from seaweed, starch from green bananas, and powdered calamansi, a local citrus hybrid, that could be reconstituted to make juice.

Not only did she revive these foods, she helped ensure their longevity. She froze and canned mangoes, canned other local fruits and vegetables, and developed preservation methods for traditional meat and seafood dishes like adobo, escabeche, dinuguan, and kilawin. Canned goods were almost exclusively imported in the Philippines at the time, making them very expensive. María wanted to ensure everyone could afford to buy preserved goods, so they could be prepared for emergencies or future bouts of food insecurity. At the 1925 Manila Carnival, the Bureau of Science exhibited María’s canned local fruits and veggies, and people were amazed.

“It was the first time people in the Philippines had seen mangoes canned whole, and the numerous other fruits preserved, and city-wide interest was aroused,” one newspaper chirped. It was so impressive that the government gave María additional funding. Now she could afford to expand her programs to teach others how to use these food preservation techniques in their own homes.

In her quest to empower families with knowledge of healthy food preparation and self-sustainability, she organized clubs modeled on America’s 4-H Club. By 1924, her clubs boasted over 22,000 members. María developed recipes utilizing native foods; she’s credited with developing over 700. Accompanied by the so-called “Orosa Girls” as demonstrators, she traveled around the islands to promote public health by teaching families about meal planning, local produce preservation, and chicken keeping. Using sheet metal and aluminum foil to reflect heat, she invented an oven version of the palayok pot so people could bake without electricity.

“Orosa’s work has to be seen in the light of the era during which she worked … when the Philippines was already on its way to establishing its independence. We needed to be self-sufficient in so many things including food,” culinary historian Felice Prudente Sta. Maria said in an April 2021 panel talk celebrating Filipino food history. Felice wrote the preface of the updated edition of Appetite for Freedom, the recipes of Maria Y. Orosa, and Essays on Her Life and Work, originally compiled and published by Maria’s niece Helen. “If the spirit of the people had not been kept alive with the help of people like María Orosa working in the food sector, in home economics, and others, if they had not instilled that strength, we would not have been able to recover in the 1940s.”

María’s shoes were always shining, and she was always wearing the latest fashions. While at the Bureau of Science, she helped create a food preservation division, which she then headed. She was sent on an international tour visiting food plants across the world to learn more about innovations in processing and canning: she spent six months in the U.S., then went on to the Netherlands, England, Germany, Spain, Italy, France, and China. Back at home, she took the helm of the entire home economics division of the Bureau of Science. She also established the Homemakers Association of the Philippines, which grew to 537 member clubs by 1941.

Her most beloved and enduring culinary invention was ketchup made from bananas. Facing a wartime tomato shortage, María substituted saba bananas to create one of the Philippines most iconic condiments. While the sauce was soon mass produced, she never made money off of this or any other of her culinary inventions. She felt they should be shared freely.

María died a war hero. Three years into the war, María’s lab was caught in a bombing raid. The employees hid in an improvised bomb shelter, but María’s foot was badly injured by shrapnel. Her assistant commandeered a pushcart and rushed her to the nearby Red Cross outpost, Remedios Hospital, which was staffed entirely by volunteers. On February 13, 1945, while Maria was still at the hospital, American artillery began heavy shelling the district from across the Pasig River. This time, the shrapnel pierced her heart. She was among the more than 500 people killed.

The Voice of Manila newspaper called February 13 “the most tragic day.” She’d had a complicated relationship with America, but in the end it was an American shell that cut short the life of a woman who dedicated herself to empowering her country with food self-sufficiency and independence.

One of María’s recipes:

‘Buko’ (coconut) Chocolate Cake

1 ½ c flour

½ tsp baking powder

½ tsp salt

¼ c butter

2 tbsp cocoa powder

½ c sugar

1 egg, well beaten

½ c grated or shredded buko (coconut strips)

¼ c milk

Preheat the oven to 375°F (180°C). Grease an 8-inch cake pan and line it with nonstick baking paper. In a bowl sift together the flour, baking powder and salt. Set aside. In a saucepan melt the butter then add the cocoa powder. Remove from heat. Add the sugar and mix well to combine. Stir in the egg and buko. Alternately mix in the milk and the flour mixture. The batter will be dense. Spoon the batter into the prepared cake pan and bake in the preheated oven for about 20 minutes. Let cool for a few minutes then transfer to a serving dish.

Further Reading:

“Maria Ylagan Orosa and the Chemistry of Resistance,” Lady Science, July 23, 2020, by Jessica Gingrich.

“War Hero Maria Orosa Invented Power Cookies. Here’s the Recipe,” Esquire Magazine Philippines, by Mario Alvaro Limos, May 30, 2020.

More About Me:

Olivia Campbell is author of the New York Times Bestseller Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine. Her essays and journalism have appeared in The Atlantic, The Guardian, Washington Post, New York Magazine/The Cut, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, HISTORY, and Literary Hub, among others. She lives outside Philadelphia with her husband, three sons, and two cats.

Order her book here, or snag a *signed* hardback copy online at Newtown Bookshop.

Amazon Author page