How Period Tracking Birthed the Calendar

Women as the first mathematicians, the first agriculturists.

We like to think of menstrual tracking as a modern technological innovation, but women throughout history and across cultures have always found innovative ways to track their cycles. Our fancy apps that remember everything about our reproductive cycles aren’t the only way to keep track. People with wombs have always wanted to know when they were fertile, when to expect their periods, and when to wonder if they were pregnant.

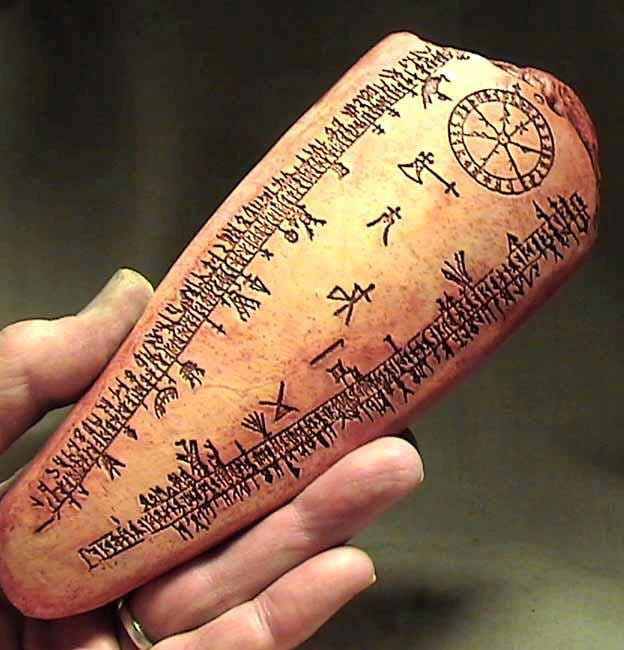

The Ishango bone is an engraved baboon fibula believed to be roughly 20,000 years old. It was found in 1960 on the shore of a lake in northeastern Zaire, what was then the Belgian Congo. Carved on its surface are three rows of notch groupings, understood to indicate 9, 19, 21, 11; 19, 12, 13, 11; and 7, 5, 5, 10, 8, 4, 6, 3. It was determined that the notches represent a six-month lunar calendar. Ethno-mathematician Claudia Zaslavsky claims the Ishango Bone served as a menstrual tracker.

“The Ishango notched bone and similar artifacts originated with a woman’s need for a lunar calendar to keep track of her monthly cycles. It is generally conceded that women were the first agriculturalists, and in that capacity they may have needed a lunar calendar,” Zaslavsky wrote.

Scholar Alexander Marshack described the groups of notch markings in this way: “... neither so placed and organized as to be decorative, nor sufficiently structured to be tattoo marks. We assume, therefore, that they are ‘storied’ and somehow notational or symbolic, and represent one of the forms of intentional marking used by man before writing. They may be counting-marks of months or menstrual periods, or marks of ‘magic’ or ‘ritual’ made as prayer or offering in a storied participation in the desire for a successful pregnancy.”

But Zaslavsky sees it as a much more open-and-shut case.

“Who but a woman keeping track of her cycles would need a lunar calendar? Zaslavsky quipped. “When I raised this question with a colleague having similar mathematical interests, he suggested that early agriculturalists might have kept such records. However, he was quick to add that women were probably the first agriculturalists. They discovered cultivation while the men were out hunting, So, whichever way you look at it, women were undoubtedly the first mathematicians!”

The oldest notched bone unearthed so far was found in southern Africa and bears 29 incisions. It is estimated to be about 37,000 years old. Though the mysteries of ovulation, menstruation, and conception were not uncovered by science until around the 19th century, before that time most people would’ve understood menstruation as a cycle; they knew that regular bleeding indicated fertility and lack of pregnancy. Recipes for treating lack of menstruation, or amenorrhea, have peppered medical texts and household recipe books since ancient times.

In Maori culture, “according to the knowledge of our ancestors and elders … the moon is the permanent husband, or true husband, of all women, because women menstruate when the moon appears.”

The Suri of southwest Ethiopia have long kept track of their menstrual cycle by counting the days with knots or beads on a small rope worn beneath their clothing. Each knot or bead represents one day and the number and kinds of knots and beads signify the different phases in their menstrual cycle. Every day, they untie one knot, and start the process over on the first day of their period.

Other traditional calendar methods evolved to include making notches on sticks to track periods and pregnancies—marking a new stick each month.

In the Native American Yurok tribe, women would place a stick a day into a basket. If they became pregnant, they would drop one stick a month into a second basket until they got to ten sticks. In Siberian cultures, women were the custodians of the calendar; the Nganasan women would sew colorful strips of fabric to a garment to count the ten months of pregnancy passing.

In Scandinavia, they used slender wooden staffs as perpetual calendars, with notches for the days of the year and descriptive characters for solstices, equinoxes, and holidays. Called primstav sticks, from the Latin for “first appearance of a new moon;” and “prim” being Old Norse for “new moon.” They are also called runstavs for their use of runic symbols.

In The Woman's Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets, feminist author Barbara G. Walker posits that calendars themselves originated with women’s tracking of their cycles: “It has been shown that calendar consciousness developed first in women, because of their natural menstrual body calendar, correlated with observations of the moon’s phases. Chinese women established a lunar calendar 3000 years ago, dividing the celestial sphere into 28 stellar ‘mansions’ through which the moon passed. Among the Maya of Central America, every woman knew the great Maya calendar had first been based on her menstrual cycles.”

What’s more, Walker notes, the Gaelic words for “menstruation” and “calculation” are the same—miosach and miosachan—and the Romans called the calculation of time “menstruation,” meaning “knowledge of the menses.” The words “rite,” “sabbath,” and “ritual” are also all derived from words pertaining to menstruation.

“Women were the first observers of the basic periodicity of nature, the periodicity upon which all later scientific observations were made,” wrote William Irwin Thompson in The Time Falling Bodies Take to Light: Mythology, Sexuality and the Origins of Culture.

It may seem outlandish to suppose fertility tracking gave rise to calendars. We’re used to “feminine” dabblings being labeled as less important, always coming second. Men were out doing the important business of hunting while women were just faffing about at home. But developing a system in which women could maintain a relatively accurate accounting of their menstrual cycles was vital to the very existence of the human race.

Further Reading:

The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation, by Janice Delaney, et al. University of Illinois Press, 1988.

Blood Relations: Menstruation and the Origins of Culture, by Chris Knight. Yale University Press, 2013.

Blood Magic: The Anthropology of Menstruation, edited by Alma Gottlieb & Thomas C. T. Buckley. University of California Press, 1988.

More About Me:

Olivia Campbell is a journalist and author specializing in women, history, and science. Her first book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, was published March 2021 by HarperCollins/Park Row Books.

Buy a *signed* hardback copy online at Newtown Bookshop.

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page

The article offers an insightful exploration of how period tracking has historically influenced the creation and evolution of calendars. Recognizing the pivotal role that women have played in monitoring their reproductive cycles highlights the importance of effective tools in this process. Utilizing a calendar template can significantly enhance modern period tracking by providing a structured and user-friendly way to document fertility, menstrual cycles, and overall reproductive health. This connection between past practices and contemporary technology underscores the enduring relevance of organized time-keeping methods. https://make-a-calendar.com/

This was such a fascinating read! I never realized how deeply intertwined period tracking and the development of the calendar are with human history. The connections you’ve drawn between ancient practices and modern technology really highlight how essential this knowledge has always been. Thank you for shedding light on such an intriguing topic—I’ll definitely be thinking about this perspective the next time I check my calendar! https://texasroadhousemenuinfo.com/