Keen Mind, Remarkable Beauty

As usual, 18th C. scientific translator Claudine Picardet's work was initially credited to her male colleagues.

Born in Dijon, France in 1735 to a wealthy family, Claudine Poulet became a brilliant scientific translator, chemist, and mineralogist.

In 1755, her marriage to Claude Picardet—an elderly barrister and councillor at one of the high judicial courts of Burgundy and member of the Dijon royal academy of sciences, arts, and literature—allowed Claudine access to France’s highest circles of science and society.

She began attending lectures and demonstrations at the academy, studying chemistry and mineralogy. She also gave birth to a son in 1757. Claudine held her own regular scientific salons, which became renowned among the academic elite of France.

“As for Madame Picardet, she held a salon, where all those who prided themselves on their knowledge of science or literature sought the honour of being admitted. She was able to enjoy the fantasy of adding her own reputation of remarkable beauty and keen mind, that of a woman of science.”

In 1764, the dashing 27-year-old Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau swept in. He was given honorary membership into the academy for his promising literary potential. But writing couldn’t hold his heart once he discovered chemistry. He inhaled everything he could about the topic and even went so far as to have a laboratory installed in his home. When a colleague who was researching combustion and calcination died, Guyton took up his work. Guyton is known as the first person to suggest naming chemicals using a uniform structure by ending the words in -ite and -ate.

A few years after Claudine’s only son died at age 19, she entered Guyton’s exclusive group of scientists tasked with translating foreign chemistry papers and books into French.

Claudine became Guyton’s protégé, his lab assistant and translator, and a scientist in her own right. Guyton’s group even performed their own experiments to verify the science of the papers and the accuracy of their translations. Guyton loved showing Claudine off, this strange, remarkable creature of both feminine beauty and scientific brilliance.

Guyton even insisted that English travel writer and agriculturalist Arthur Young meet this “learned and agreeable young lady” when visiting. Young recorded:

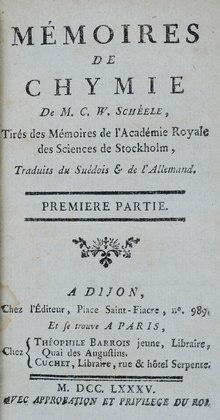

“Madame Picardet is as agreeable in conversation as she is learned in the closet; a very pleasing unaffected woman; she has translated Scheele from the German, and a part of Mr. Kirwan from the English; a treasure to M. de Morveau, for she is able and willing to converse with him on chemical subjects, and on any others that tend either to instruct or please.”

British chemist Richard Kirwan was clearly jealous, telling Guyton “you are very lucky to have such a lady who wants to translate the papers of M. Scheele. I find her incomparable.”

Incomparable, indeed, even—or perhaps especially—among her male counterparts. Claudine translated thousands of pages: Swedish, German, Italian, Latin, and English texts on chemistry, mineralogy, and astronomy into French. In the translators group, Claudine was the only woman, the only non-academic. She could translate the most languages and was the most prolific by far. She was also the only one to publish papers in journals outside the Annales de chimie, France’s leading chemistry journal created by Guyton, Antoine Lavoisier, and Claude Louis Berthollet.

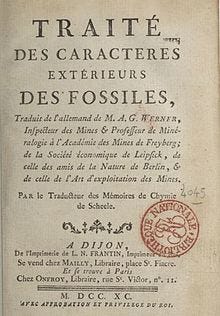

She was, in fact, the most-published translator of chemistry papers in France in the 1780s. In her translation of Werner’s color system, Claudine added a further 17 colors to Werner’s list. She translated Bergman’s “Opuscula physica et chemica” from Latin into French. She added commentary and a methodological note about her translation in her edition of “Traité des caractères extérieurs des fossiles.”

After Claudine’s husband died in 1796, she moved into an apartment in Guyton’s house in Dijon. By this time, Guyton had moved to Paris, so before long, she moved in with him there.

When she was rich, Claudine also assisted Guyton financially. When he later became financially destitute, she married him.

Initially, credit for her work was largely given to Guyton and others in the group. But luckily, clear evidence of her authorship was since unearthed. Claudine’s impact upon science cannot be understated. She contributed to the universalization of science. Her work proved crucial to scientific developments in chemistry and mineralogy in the 1700s and 1800s, since so much of science hinges on building on what others observe and discover.

More About Me

Olivia Campbell is the author of the New York Times bestseller Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine. Her essays and journalism have appeared in The Atlantic, The Guardian, Washington Post, New York Magazine/The Cut, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, HISTORY, Catapult, and Literary Hub, among others. She lives outside Philadelphia with her husband, three sons, and two cats. Find out more about her life and work on her website.

Order her book on Bookshop.org, Amazon, or grab a *signed* hardback copy online at her local independent bookstore, Newtown Bookshop.