Mapping Philadelphia's Flora

The prowess of plant physiologist Ida Augusta Keller

The botanical community was abuzz with the news of Ida A. Keller’s grand plan for a comprehensive guide to Philadelphia-era flora. It was a massive undertaking, the scope of which was unheard of at the time, let alone undertaken by a woman.

“... she is preparing a catalogue of the plants growing within a circuit of one hundred miles around that city. When some of us were active collectors, a flora of twenty miles around any one centre would be the height of an author’s ambition,” an unknown author practically squealed in an article in the May 1897 issue of Meehans' Monthly: A Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and Kindred Subjects. “Dr. Barton had ‘a flora of twenty miles around Philadelphia,’ but his stations are now nearly all covered by bricks and mortar. In these days of steam and electricity a hundred miles can be examined in less time and at less cost than twenty could in the beginning of the century.”

Ida was confident her guidebook wasn’t biting off more than she could chew; she knew she could produce a sprawling, exhaustive compendium. Ida’s reputation as a superior scientist had preceded her, as the article noted: “The lady is equally known as a profound botanist and successful teacher of chemistry.”

In 1905, she and co-author Stewardson Brown finally published the Handbook of the flora of Philadelphia and vicinity, a 360-page guide to the region’s flora. Her incredibly ambitious project had been fully realized.

Botany was one of the first scientific fields into which women were allowed to make professional inroads. Playing with plants and flowers was deemed a suitably feminine pursuit. Men fought the push of women into what they perceived as their domain of Science, of work that required critical and analytical analysis, at every turn. Such things took big man brains. Like grumpy, harrumphing toddlers, they stamped their feet and demanded “No GIRLS allowed” in their clubhouse. Their fists clasped around their precious sciences, they eventually relented, peeling away one finger at a time to allow women in, discipline by discipline.

Ida’s parents were German immigrants to Pennsylvania. Dr. William Keller and his pregnant wife Maria were visiting their homeland of Germany when their daughter Ida decided to make her appearance, on June 11, 1866. The family soon returned to America.

After graduating from the Philadelphia High School for Girls in 1884, Ida became the first woman to complete the University of Pennsylvania’s two-year biology program. But instead of a degree, she received a Certificate of Proficiency in Biology. The university couldn’t possibly grant a *degree* to a *woman*!

Her first professional experience was working as an assistant at the Bryn Mawr College herbarium. Bryn Mawr was a women’s college northwest of Philadelphia that had just opened in 1885. Eager for a more-advanced academic experience than most American universities were ready to supply to a woman, Ida was off to the University of Leipzig in Germany. For two years, she studied chemistry with the eminent Friedrich Stohmann and plant physiology with the foremost expert of the day, Wilhelm Pfeffer. Pfeffer ran the botanical garden at the institution. Ida had to leave Germany to earn her doctorate. At the University of Zürich, Switzerland, she finally earned her PhD in 1890. Ida’s dissertation was titled Über Protoplasma-Strömung im Pflanzenreich (On Protoplasmic Flow in the Plant Kingdom).

She was the second of a series of American women driven overseas for advanced botany degrees. To the University of Zürich, specifically. Emily L. Gregory left her position as Bryn Mawr botany professor to earn her doctorate there in 1886. Emily was the first woman invited to become a member of the American Society of Naturalists. Ida became the second. It was likely the prestige carried by their foreign credentials that earned them a seat at the table. Two women whose PhDs were from Syracuse University were not permitted to join the group.

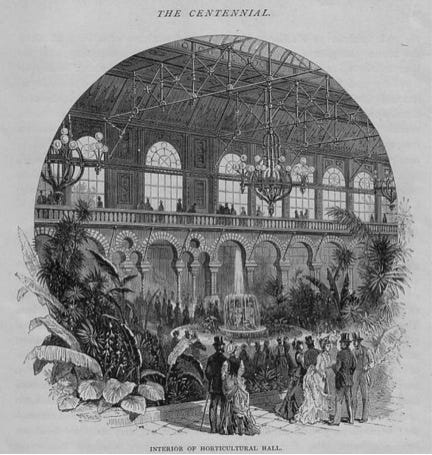

It was incredibly rare for women to be allowed into professional science societies at the time. But Ida continued to make headway in this arena. Over the course of her career, she was made a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, an honorary member of the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, and a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. In December 1900, she was elected to the Executive Committee of the Botanical Section of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia along with her co-author Stewardson Brown. Unfortunately, she was also a member of the American Eugenics Society in its very early days, though she seems not to have been a particularly active member. Where she was an active member was in local women's suffrage organizations.

Ida was the first woman member elected into the Philadelphia Botanical Club (est. 1891) and before long was serving as the club’s vice president; she remained its only woman member for several years. The group was a lively and energetic bunch; their field trips could last several days.

In her research, Ida took a special interest in plant morphology and fertilization. She was well-known among her scientific peers for her eminence in vegetable morphology in particular. The Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia published several of her papers. Of plant “monstrosities,” or abnormal growth, Ida wrote in the journal in 1897: “deformities in plants are extremely interesting. Although there can be no doubt that the investigator should above all things seek the explanations of their causes, in the present state of our science it is impossible to discover in most cases the reasons for their occurrence.”

Upon her return from Zürich, Ida became a botany lecturer at Bryn Mawr. She soon decided she’d rather apply her skills toward inspiring a love of science in younger girls and began teaching chemistry at her alma mater, the Philadelphia High School for Girls. By 1898, she was head of the chemistry and biology departments. In addition to her Philadelphia guidebook and scientific papers, Ida also authored high school lab manuals and a booklet on local insects.

Ida regularly took her students out for field work, and brought any specimens of special interest they collected to the attention of the Philadelphia Academy of Science. Thanks to her encouragement to observe and collect interesting plants, her students began to make discoveries on their own.

On her walk home from school in southern Philadelphia, Adelaide Allen noticed a unique plant growing alongside a dyke running to South Broad Street near League Island Park en route to the farmhouses outside the city. From the flats and marshes off the Delaware, Adelaide plucked a cool plant and brought it to her teacher Ida. It turned out to be a plant species never before found growing wild in the U.S.: Eurasian Muscari comosum, or tassel hyacinth.

“The region is not yet built up to any extent and the more elevated portions are frequently occupied by truck-farms. The southern extension of Broad Street, with its trolleys, offers one of the chief lines of travel in this particular locality, and the nearby farms often obtain access thereto by dykes laid down over the low meadows and more impassable places. These dykes are continually augmented by the dumping of ashes and rubbish down their sides,” the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia noted of the exciting find in January 1922. “In such a habitat, from a detailed sketch-map furnished by Miss Allen, the Muscari was found growing.”

Among the specimens Ida donated over the course of her career: Virginia bluebells, Lyre-leaved rockcress, spreading rockcress, rattlebox, ragged-fringed orchid, scarlet painted-cup, wild sweetwilliam, tall thimbleweed, Carolina rose, and riverbank grape.

In 1930, Ida finally retired. She’d enjoyed a glorious 32-year teaching career inspiring countless girls to pursue science by showing them the joy and wonder of scientific curiosity. She died two years later, at her summer home in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, at the age of 66.

More about me:

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page

Order my book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, out March 2, 2021 from HarperCollins/Park Row Books.

Buy a *signed* hardback copy online at Newtown Bookshop.