She's a Witch!

When suspicion falls on midwife Margaret Jones, she becomes the first victim of the Massachusetts Bay Colony's witch trials

Margaret Jones, along with her husband, Thomas, their 3-year-old daughter Sarah and newborn, John, arrived at Massachusetts Bay Colony from England in 1634. The colony had only been established a mere four years prior. Theirs was one of 30 ships to arrive in the Bay that year, a mass migration of Brits to the new world. As of May 1634, Boston Governor John Winthrop reported a (non-Native) population of 4,000. Immigrants to New England would reach 20,000 by the end of the decade.

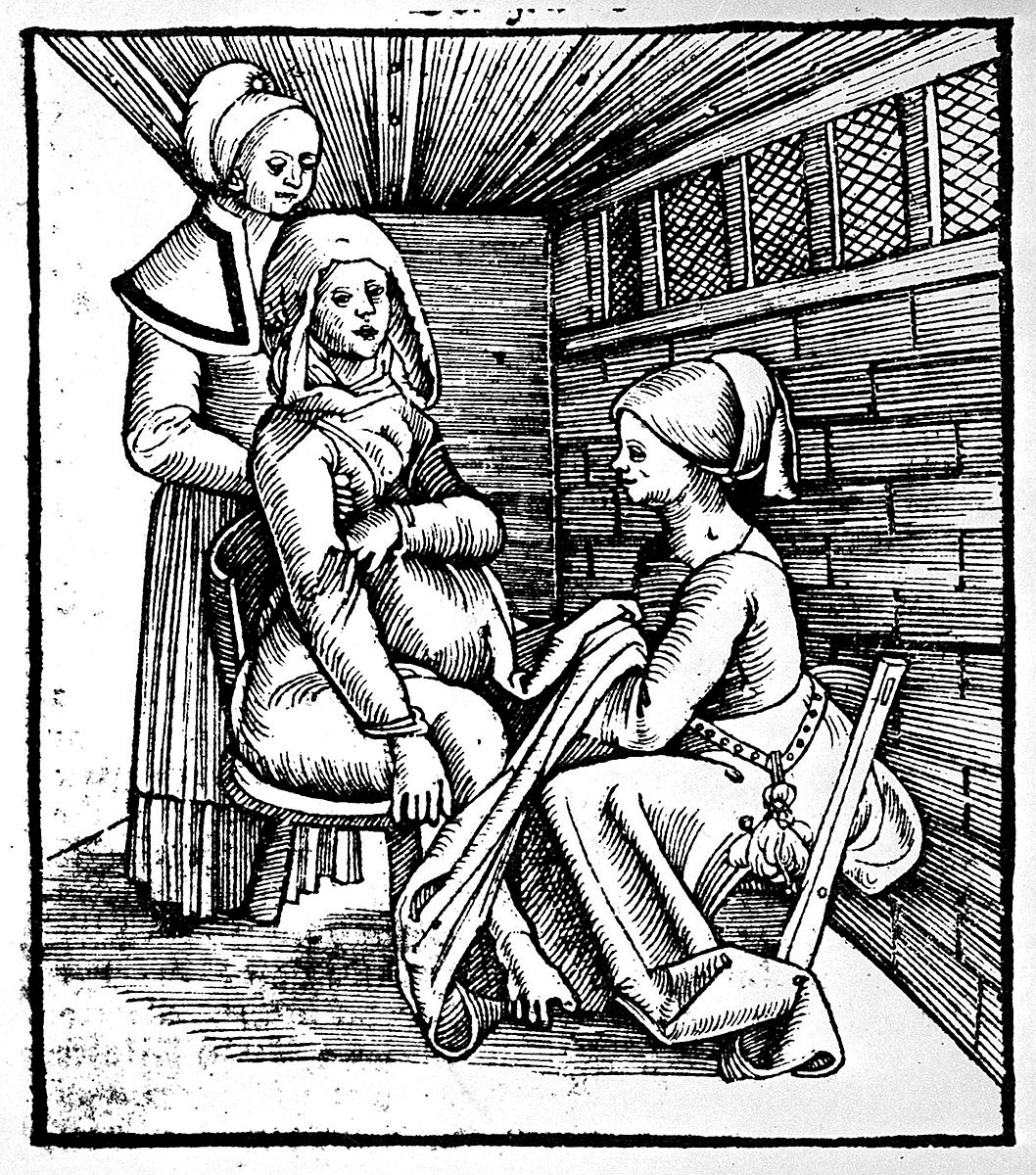

Margaret became one of the colony’s trusted midwives and healers. At the time, midwives were generally highly valued and well-respected members of the community. It was common for communities to hire a midwife by offering her a house, land, or salary in exchange for her services. In New Amsterdam, the Dutch West India Company actually employed midwives beginning around the 1630s.

I recently wrote about how making medicines was closely tied to culinary endeavors in this early-modern colonial era for Smithsonian Magazine. Knowledge of basic first aid and healthcare was expected of women as managers of their households. Recipes for medicinal tinctures, ointments, and various other remedies appeared alongside those for breads and pies in household cook books. Even deeper knowledge of these topics would’ve been expected of the village healer.

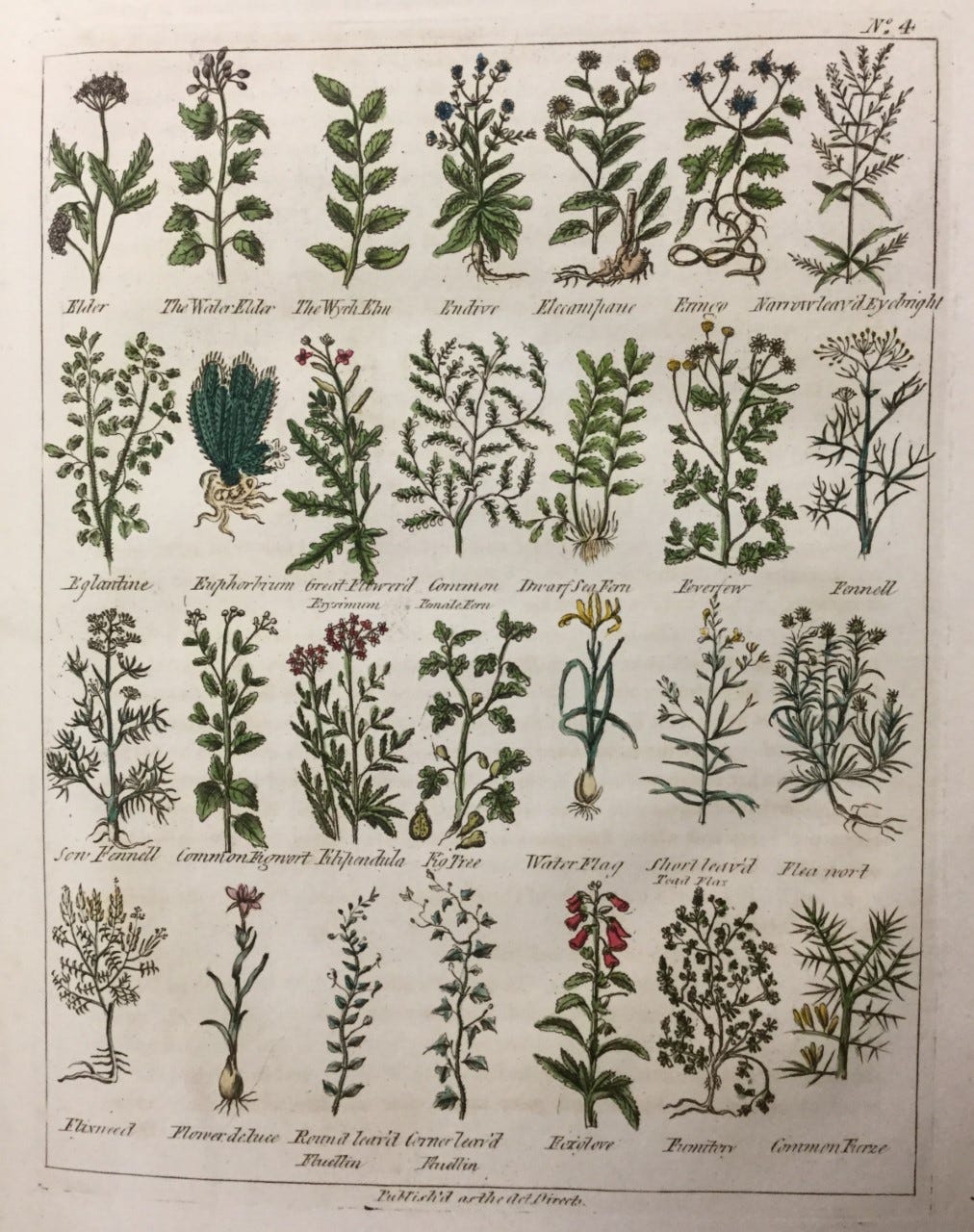

Midwives also acted as the local healers in colonial America. Using time-tested folk medicine knowledge passed down orally through family members or apprentices over generations, wise women would tend the sick, proffer herbal remedies, and prepare the dead for burial. She was just as skilled as an apothecary and nurse as she was at delivering babies. In essence, we have lay women healers to thank for the survival of the early North America settler colonies.

“The geographic isolation of settlers in the North American colonies meant that the knowledge of female healers, particularly in regards to botanic, or plant-based, medicines, was vital to the survival of new settlements,” notes Elise Helmers, director of New York’s Bowne House Historical Society.

Indeed, a folk healer’s most powerful weapon was her garden (and the knowledge she possessed about when to plant and harvest and how to prepare each herb for maximum benefit). Though we don’t know whether or not Margaret was a midwife/healer back in England, if she had been, she likely would’ve brought seeds for medicinal herbs with her on the transatlantic voyage. (Margaret was only 21 when she arrived in America after all.) One school of medical thought at the time asserted that local plants healed local people, meaning the best herbs to cure sick Europeans were native European herbs.

But dealing in illness and childbirth meant your patients didn’t always survive, or that they got worse. Babies are often born with deformities, and birthing parents and babies can be injured during childbirth. Whether or not this was the fault of the medical practitioner seemed neither here nor there, since mere proximity to deformity, illness, injury, and death rendered healers and midwives automatically potentially under suspicion.

For 13 years, the Jones family lived and worked in relative peace in the New World. But that all came to a catastrophic halt on June 15, 1648, when 35-year-old Margaret became the first woman executed for witchcraft in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. She was killed by hanging from an elm tree. She was indicted and executed on the same day.

This is the evidence given against her, as reported in the court record:

“1. That she was found to have such a malignant touch, as many persons, men, women, and children, whom she stroked or touched with any affection or displeasure, or etc. [sic], were taken with deafness, or vomiting, or other violent pains or sickness.

2. She practising physic, and her medicines being such things as, by her own confession, were harmless, — as anise-seed, liquors, etc., — yet had extraordinary violent effects.

3. She would use to tell such as would not make use of her physic, that they would never be healed; and accordingly their diseases and hurts continued, with relapse against the ordinary course, and beyond the apprehension of all physicians and surgeons.

4. Some things which she foretold came to pass accordingly; other things she would tell of, as secret speeches, etc., which she had no ordinary means to come to the knowledge of.

5. She had, upon search, an apparent teat ... as fresh as if it had been newly sucked; and after it had been scanned, upon a forced search, that was withered, and another began on the opposite side.

6. In the prison, in the clear day-light, there was seen in her arms, she sitting on the floor, and her clothes up, etc., a little child, which ran from her into another room, and the officer following it, it was vanished. The like child was seen in two other places to which she had relation; and one maid that saw it, fell sick upon it, and was cured by the said Margaret, who used means to be employed to that end. Her behavior at her trial was very intemperate, lying notoriously, and railing upon the jury and witnesses, etc., and in the like distemper she died. The same day and hour she was executed, there was a very great tempest at Connecticut, which blew down many trees, etc.”

Puritan pastor John Hale, who would play a large role in the Salem witch trials five decades later, witnessed Margaret’s hanging in Boston as a young boy. He wrote this account of the grievance that preceded the accusations of witchcraft against Margaret:

“She was suspected partly because that after some angry words passing between her and her neighbors, some mischief befell such neighbors in their creatures, or the like. Partly because some things supposed to be bewitched or have a charm upon them, being burned, she came to the fire and seemed concerned.

The day of her execution, I went in company of some neighbors, who took great pains to bring her to confession and repentance. But she constantly professed herself innocent of that crime. Then one prayed her to consider if God did not bring this punishment upon her for some other crime and asked if she had not been guilty of stealing many years ago; she answered, she had stolen something, but it was long since and she had repented of it, and there was grace enough in Christ to pardon that long ago; but as for witchcraft she was wholly free from it, and so she said unto her death.”

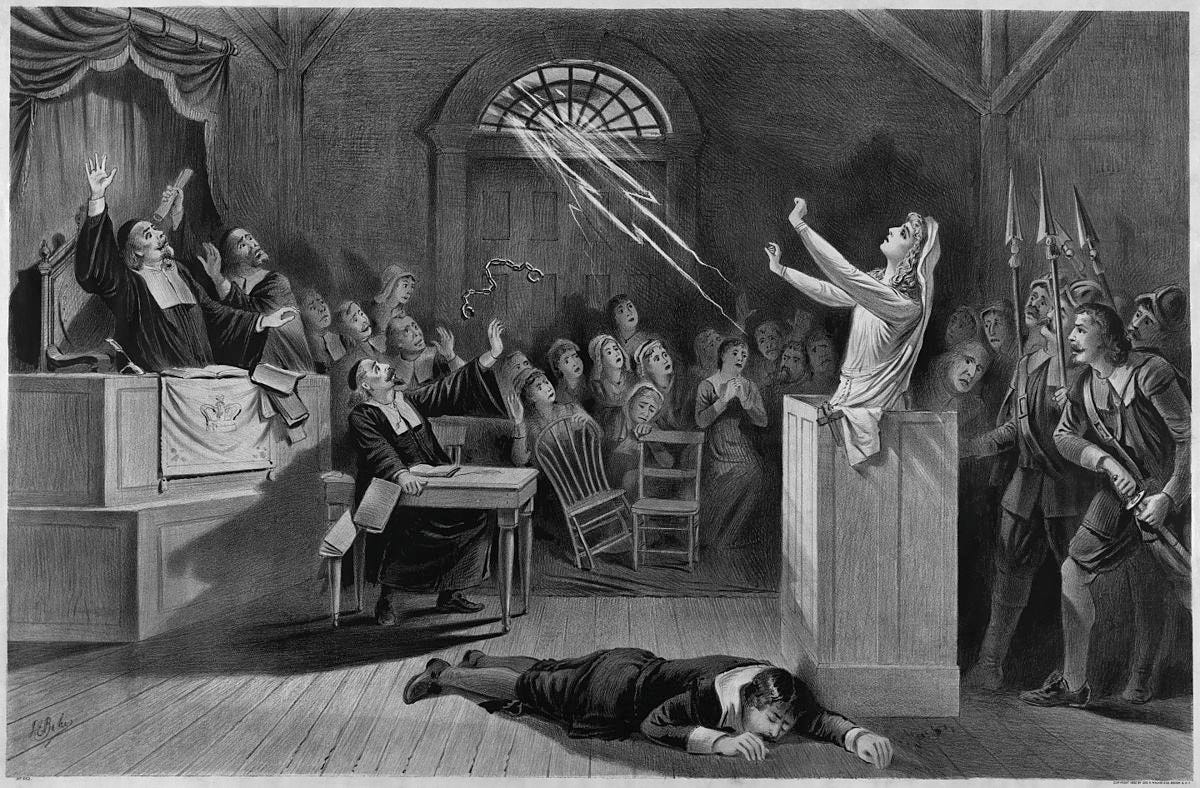

The earliest recorded New England witchcraft execution was the year before Margaret’s, when the killing of Alse Young marked the beginning of the Connecticut witch trials. These trials lasted until 1663 and saw the execution of nine men and two women. Witchcraft trials of course reached a fever pitch in Salem, Massachusetts in 1692. By the following year, the town’s witch hunt had seen 200 people charged with witchcraft (largely women), with 19 killed by hanging, five dead as a result of their incarceration, and one man pressed to death.

And even if you survived a witch trial, merely being suspected of witchcraft could mark you as trouble among your community. After poor Mary Webster was found “not guilty,” her neighbors in Hadley, Massachusetts pursued the Puritan practice of witch “disturbing” to prevent her from casting spells. She was dragged out of her home, hung from a tree until on the brink of death, then buried in the snow and left for dead. Though miraculously, she did not die, she was known from then on as “Half-Hanged Mary.”

These New England witch hunts were an unfortunate carry-over from Europe, where the church/state had been hunting witches since the 1400s. Women healers were among the main targets in the crusade that saw roughly 100,000 people killed by the 1700s.

Modern culture treats witches similar to how it treats pirates: as cutesy characters watered down and stripped of all their true traits. Most witches are depicted as gently spooky and only slightly more powerful than magicians. (Either that or they are portrayed as devil worshippers.) In reality, witches are largely just practicing an ancient pagan, earth-revering religion.

But this isn’t really about the actual practice of witchcraft so much as it is about suspicion, Satanic panic, and the deadly lengths neighborhood beefs can go to. Writing about witches for spooky season should be fun, but I couldn’t stop thinking about how many innocent women's lives were taken by witch hunts, how much hard-earned knowledge of folk medicine and herbal remedies was lost, how many women lost access to a qualified healthcare practitioner in their community. It just makes me feel sad, not spooky.

As an aside, I am descended from a convicted Salem witch. Rebecca Blake Eames (sometimes Ames) was born in Massachusetts in 1641. She was accused of witchcraft while watching another witchcraft trial in August 1692. She confessed and was tried and convicted less than a month later alongside nine other women. All of them were sentenced to death. Four were executed, but before they could get to the rest, the witchcraft court was dissolved and Rebecca recanted her confession, saying she was told that confessing would make things easier for her. She was set free and lived until the age of 80. She is 12 generations back from me. I’d love to be able to say something astonishing and meaningful like “if she hadn’t been set free, I wouldn’t exist!” but by the time she was convicted, she’d already birthed all eight of her children.

Further Reading

“Does Science Persecute Women? The Case of the 16th-17th Century Witch-Hunts” by Karen Green and John Bigelow. Philosophy 73, no. 284 (1998): pp. 195–217.

“Medicine in New Amsterdam” by Claude Edwin Heaton. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 9, no. 2 (1941): pp. 125–43.

A Modest Enquiry Into the Nature of Witchcraft by John Hale, 1697

More About Me:

Olivia Campbell is the author of the New York Times bestseller Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine. Her essays and journalism have appeared in The Atlantic, The Guardian, Washington Post, New York Magazine/The Cut, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, HISTORY, Catapult, and Literary Hub, among others. She lives outside Philadelphia with her husband, three sons, and two cats. Find out more about her life and work on her website.

Order her book Bookshop.org, Amazon, or grab a *signed* hardback copy online at my local independent bookstore, Newtown Bookshop.