The Chemist Who Exposed a Cancer Cure Fraud

Alma LeVant Hayden, the first Black scientist at the FDA, busts the Krebiozen scam

I imagine there was a sort of collective breath-holding as Alma LeVant Hayden gingerly opened the small ampule, surrounded by a team of experts the government had assembled. This was far more ceremony than usually afforded the testing of an unknown substance, but that’s because this was no ordinary substance. This was something a small group of doctors had convinced the nation was a miracle cancer cure-all, yet the contents of which they refused to divulge.

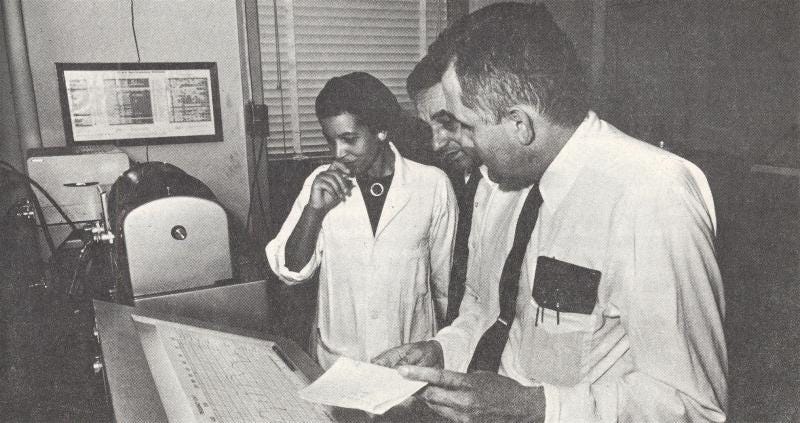

It was September 3, 1963, and Alma had only been named director of the FDA’s spectrophotometry branch in the agency’s division of pharmaceutical chemistry three months prior. Still, she was confident that her 12 years of experience as a chemist would be more than enough to get to the bottom of this mystery.

Alma Jerlene LeVant was born on March 30, 1927 in Greenville, South Carolina. In 1947, she graduated with honors from South Carolina State College. Originally intending to become a nurse, when Alma discovered chemistry in college it was love-at-first-experiment. She said she “just didn’t want to part from it,” so she pursued a graduate degree in chemistry at Howard University, under prominent research chemist and professor Lloyd Noel Ferguson.

The National Institute of Health’s Institute of Arthritic and Metabolic Diseases hired Alma as an organic chemist in 1951, and she later became a steroid chemist there. She analyzed organic substances, synthetic analogs, and used paper chromatography to identify steroids. Alma married fellow NIH research chemist, Alonzo R. Hayden.

After five years, Alma took a position as an analytical chemist in the FDA’s Division of Pharmaceutical Chemistry. She is believed to be perhaps the first Black woman scientist employed by the FDA. In a December 1946 interview, an FDA information officer stated “there are no colored scientists employed by the agency. Those working in the field occasionally have to appear in court to support a case or offer testimony on findings. A colored person might prejudice the case in court, in certain sections of the country.”

Luckily, these racist fears appear to have faded over time, at least enough for the agency to recognize they couldn’t pass up the chance to employ Alma and her brilliance. Alma would indeed provide testimony in a court case, a major one that saw her under a national spotlight. Would the racism of the jury see her research discounted?

She was always working to stay up to date on the latest cutting edge technologies in her specialty. Paper chromatography had only recently been discovered when she began using it; it won its inventors the chemistry Nobel Prize in 1952. Already well-versed in infrared spectroscopy, Alma also became a noted expert in spectrophotometry, another brand-spanking-new chemical analysis technique.

Alma’s skill in infrared spectroscopy proved uniquely valuable to the FDA. Within just a few years, she had already published 17 scientific papers, writing about infrared analysis of pharmaceuticals, micro-extraction techniques, steroid identification, and the comprehensive “Infrared, ultraviolet, and visible absorption spectra of some USP and NF reference standards and their derivatives.”

Six months before Alma was named head of the FDA’s spectrophotometry branch, congress had enacted reforms in federal drug regulation in the wake of the Thalidomide tragedy. These reforms were aimed at ensuring the safety and efficacy of drugs through stricter clinical testing and marketing standards. Clinical research would now be undertaken under the explicit authorization of the FDA.

One application filed just after these reforms aroused “a profound feeling of skepticism.” Now, it was up to Alma to determine what form of snake oil these quacks had been selling to desperate cancer patients. What, exactly, was Krebiozen?

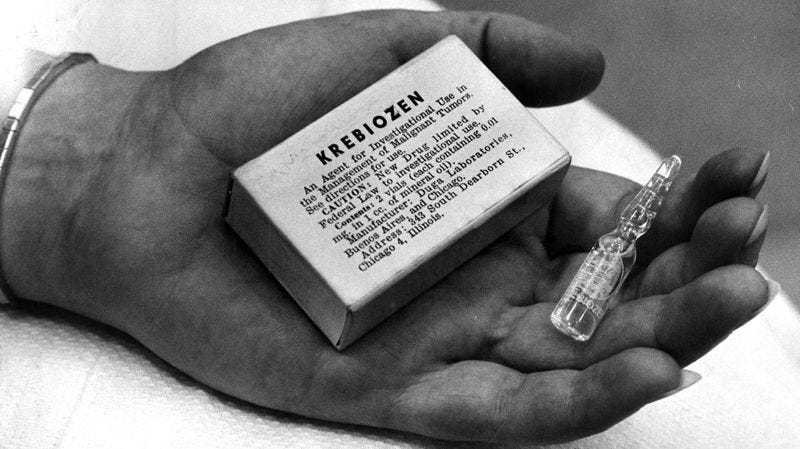

In 1946, a Yugoslavian physician living in Argentina, Stevan Durovic, created a drug he called Kositerin by extracting the blood serum of cattle he treated with Actinomyces bovis (the bacteria responsible for lumpy jaw). He believed it may treat high blood pressure. Durovic brought the substance to Northwestern University, where its therapeutic potential was proven nonexistent. But he wasn’t going to admit defeat that easily. He was referred to prominent physiologist Andrew Conway Ivy (executive director of the National Advisory Cancer Council and author of the Nuremberg Code of ethics for human experimentation). Durovic regaled Ivy with tales of how he’d successfully treated cancer in animals with this drug he’d created from horse blood serum, now dubbed Krebiozen. “Some scoffers assert that Kositerin became Krebiozen during a cab ride across town,” Time Magazine quipped.

The drug promoted natural resistance to tumors, Durovic insisted. Ivy needed little convincing, and his team set about injecting 22 terminal cancer patients. Instead of publishing the results in a peer-reviewed journal, Ivy called a press conference in 1951. A big red flag. Ivy insisted it wasn’t suspicious: that word of his amazing cancer cure was spreading, so he needed to get ahead of the gossip. To an excited audience of journalists, politicians, doctors, and potential investors, Ivy announced that of the 22 patients he’d treated, 14 were still alive and none had died of cancer. The truth was that 10 of the patients had already died of cancer. Ivy refused to spell out the contents of the drug. An enormous red flag.

But his reputation went a long way to obscure these flags. All that hopeless patients could see was hope.

Several physicians and researchers tried to reproduce Ivy’s results. Yet again, its therapeutic potential was proven nonexistent. Over the next decade, thousands of patients received Krebiozen injections, paying $9.50 per ampule (about $87 per treatment in today’s money) despite lack of any credible evidence of its effectiveness. Subsequent research showed that most doctors only treated one patient, no more. Another red flag. One suspicious doctor requested ampules of the drug for his patients who’d received a “bilateral pneumonectomies” aka the surgical removal of both lungs. Even though such patients couldn’t possibly exist, the medicine was sent, along with the bill.

Defenders of the drug demanded that there was a conspiracy to keep Krebiozen off the market. In 1960, the Citizens Emergency Committee for Krebiozen sent out 25,000 copies of its bulletin, encouraging people to protest the American Cancer Society's fund drives. Newspaper headlines demanded “Real Hope To Cure Cancer” and “Big Lie Bans Cancer Drug.”

During attempts to vet Krebiozen, the National Cancer Institute requested large amounts of the drug for testing. The drug-makers said it would cost $170,000 a gram. Finally, after repeated requests, samples were provided, free of charge, to the NCI and the FDA. The FDA also analyzed samples obtained by patients.

Alma Hayden and her team got to work identifying the drug’s contents using infrared spectrophotometry. The tracings indicated the presence of an amino acid. Alma instructed summer intern Ruth Kessler to look for a match to the sample within their library of 20,000 chemical chromatograms. Ruth proceeded through the library in alphabetical order. Luckily, she discovered a match near the beginning of the alphabet: creatine. Krebiozen was simply an amino acid naturally present in muscle cells, suspended in mineral oil. Using thin layer chromatography, gas chromatography, and other microanalytic techniques capable of detecting as little as 1 part in 10 million, in some of the samples, nothing but mineral oil was found. Krebiozen was a scam, and Alma had proved it.

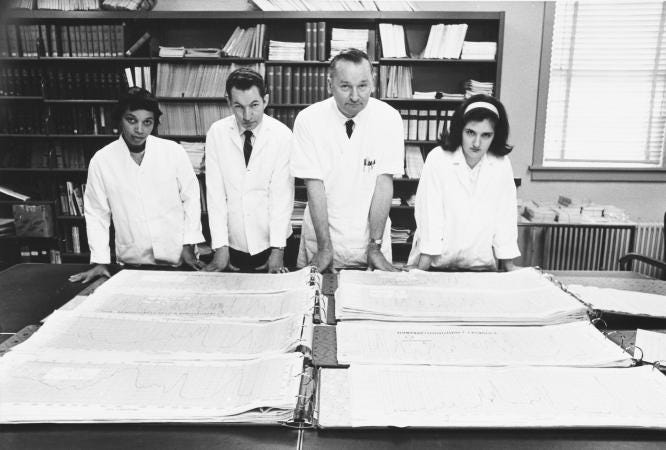

In April 1965, Ivy, Durovic, and his brother Marko were brought to trial on charges of fraud and FDA regulation violations. Alma was one of 179 witnesses to testify at the trial, with evidence in the case totalling 20,000 pages. She provided irrefutable evidence that Krebiozen was merely creatine. This fact was presented alongside evidence of the drug having no effect in 504 patients, and drugmakers falsifying reports of at least one patient, claiming he was alive six years after he’d died. It seemed like an open-and-shut case.

But the defense declared the science couldn’t be trusted, cried conspiracy. After 8 days spent deliberating, the jury was “hopelessly deadlocked.” In January 1966, the defendants were acquitted, a hung jury declared. Years later, it was discovered that one juror had been influenced by pro-Krebiozen propaganda during the trial (he was jailed for contempt). Durovic was soon indicted for tax evasion and fled the country.

In a cruel twist of fate, it turns out Alma could’ve used a miracle cancer cure. Her life was tragically cut short when she died of cancer on August 2, 1967 at the age of 40, leaving behind her two children, Michael and Andrea.

Theranos and ivermectin are just the latest in a long tradition of American healthcare scams, frauds, and snake oil salesmen. We can only hope that as long as there are medical hucksters in the world, there are always Alma Haydens to take them down.

Further Reading:

“Alma LeVant Hayden's Contributions to Regulatory Science,” the FDA.

“Alma Levant Hayden: First Black woman in the FDA,” Medical News Today, by Kimberly Drake, February 19, 2021.

“The doctor said it could cure cancer. The federal chemist proved that it couldn’t,” The Washington Post, by John Kelly, August 26, 2017. (paywall)

“Krebiozen: the cancer 'cure' that was a fraud,” The Chicago Tribune, by Ron Grossman, September 25, 2018.

More about me:

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page

Order my book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, out now from HarperCollins/Park Row Books.

Find a paperback at Costco, where Women in White Coats is the March Buyers’ Pick.

Buy a *signed* hardback copy online from my local indie, Newtown Bookshop.