The Fairer Sex Upends an Unfair Fair

How Women Inventors Revolutionized the Home By Creating Their Own Space at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exposition

The Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876 introduced America to the telephone, the qwerty keyboard typewriter, bananas, Heinz ketchup, a dishwasher, self-heating iron, interlocking bricks, emergency flares, and a portable 6-horsepower steam engine. The last five of these were invented by women. In fact, more than 80 patented inventions created by women were presented, most of which were intended to provide ladies with less housework and more leisure time. But none of them were allowed to be presented in the main exhibition hall.

Several women had been heavily involved in the planning of the exposition. The Women’s Centennial Committee raised more than $2,000,000 (!!) for the fair (worth about $55,300,000 today), so they were granted exhibition space for women inventors inside the 20-acre main building. That was until more international groups expressed interest in presenting, and the all-male Centennial Board sold off the women’s space.

Led by Elizabeth Duane Gillespie, great-granddaughter of Ben Franklin, the Women’s Committee had to act quickly to plan, fund, and construct their own freestanding 30,000-square-foot building if they were to be included in the fair. Just in time, the Women’s Pavilion was erected. All of the exhibits inside, from farming equipment to sewing machine attachments and artworks, were created by women. It was the first international exhibition dedicated to showcasing American women’s ingenuity.

The inventions on display at the women’s pavilion included a bag that turned into a chair, a 7-foot tall desk that could collapse down to 18 inches, a self-draining flower stand, several stoves and dishwashers, an iron with a heat-proof handle, interlocking hollow bricks, and a bed frame with drawers. Unfortunately, brick inventor Mary Nolan failed to file a patent, so her creation was quickly copied, while the more business-savvy Elizabeth Stiles’ patented folding “Stiles Desk” went on to some success.

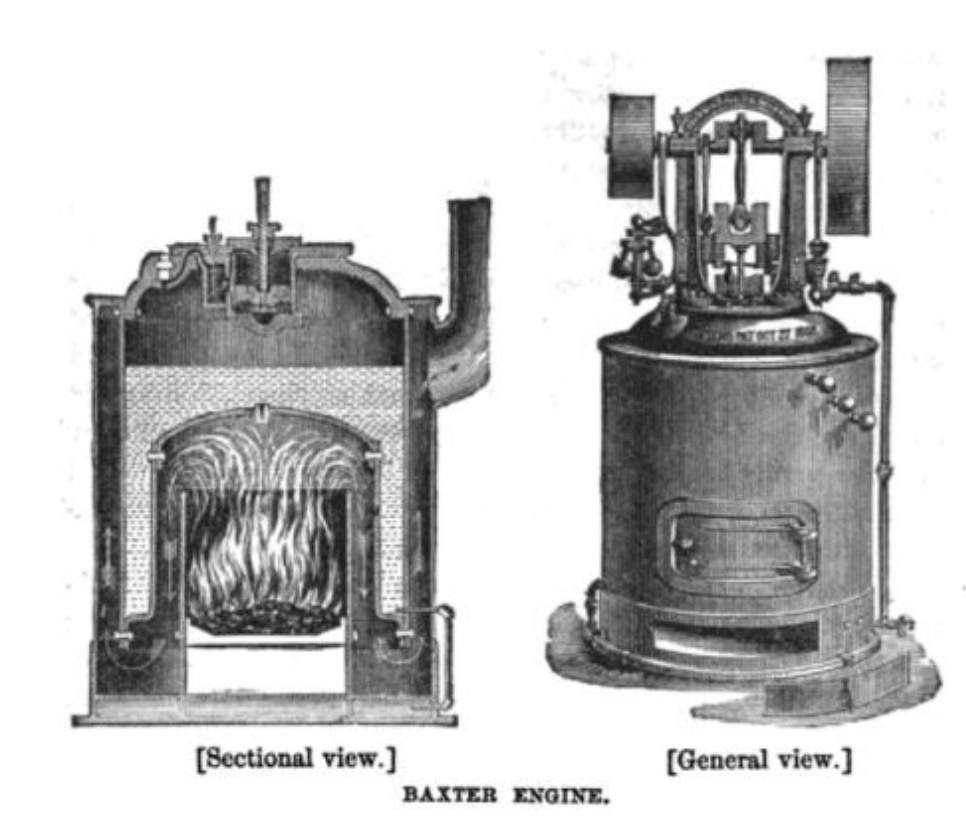

Engineer Emma Allison proudly presented her Baxter Engine. Dressed up in her Sunday best, she arrived at the exhibition hall early in the morning and tended her “iron pet” all day. The engine powered all of the other machines in the pavilion, including a printing press that was churning out copies of the Women’s Centennial Committee’s newsletter, The New Century for Women.

“There was, of course, much opposition to the project,” the women’s newsletter reported. “One of the arguments being that the committee would some day find the Pavilion blown to atoms and it would be discovered that the female engineer had lost herself in some interesting novel when she ought to have been watching the steam-gauge.”

Emma herself was treated as the most curious of all the attractions. “Perhaps the most interesting object in the woman’s edifice is the lady engineer,” proclaimed Scientific American.

The end of the Exposition was far from the end for these women. Wanting to maintain the momentum of feminine fire that the Exposition had sparked among them, the ladies quickly brainstormed how to create new arenas where their camaraderie, discourse, and education could continue. In January 1877, forty women involved in the Exposition founded the New Century Club in Philadelphia, one of the first women’s clubs in the country.

A self-described “centre of thought and action among women,” it served as a meeting place to discuss science, literature, and art. But the organization wasn’t solely for the intellectual edification of bored upper-class ladies. Members could access its extensive library and the group offered job training, weekday room and board, and support to working women. It also promoted social reform on issues such as child labor laws and education.

The Centennial Exposition proved a turning point in public conversation and the eventual acceptance of women inventors and engineers. The inventions presented by women—and largely for women—helped lessen workloads and improve safety across the world. And the ladies knew just what you should do with that newfound spare time: come to the women’s club to expand your horizons. Finally, women’s sphere was expanding beyond the domestic realm. The women’s club that grew out of the event provided a national model of how to help women expand their professional and educational reach, and how to advocate for the welfare of all working women.

Further Reading

“Toward a New Century: Women and the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, 1876,” by Mary Francis Cordato, Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 107, no. 1 (1983): 113-136.

Gendering the Fair: Histories of Women and Gender at World’s Fairs. Abigail M. Markwyn and Tracey Jean Boisseau, eds. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2010.

“Emma Allison, a ‘Lady Engineer’” by Robert Davis, Lady Science. 2017.

More About Me

Olivia Campbell is the author of the New York Times bestseller Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine and a health editor at Dotdash Meredith. Her essays and journalism have appeared in The Atlantic, The Guardian, Washington Post, New York Magazine/The Cut, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, HISTORY, Catapult, and Literary Hub, among others. She lives outside Philadelphia with her husband, three sons, and two cats. Find out more about her life and work on her website.

Order her book on Bookshop.org, Amazon, or grab a *signed* hardback copy online at her local independent bookstore, Newtown Bookshop.