The First Lady of Limu

Isabella Aiona Abbott breaks barriers as a Native Hawai'ian woman scientist.

The flashy colors, fervent fragrance, and flamboyant physique of flowers didn’t fool Isabella, affectionately known as Izzie. She saw right through their showy seduction.

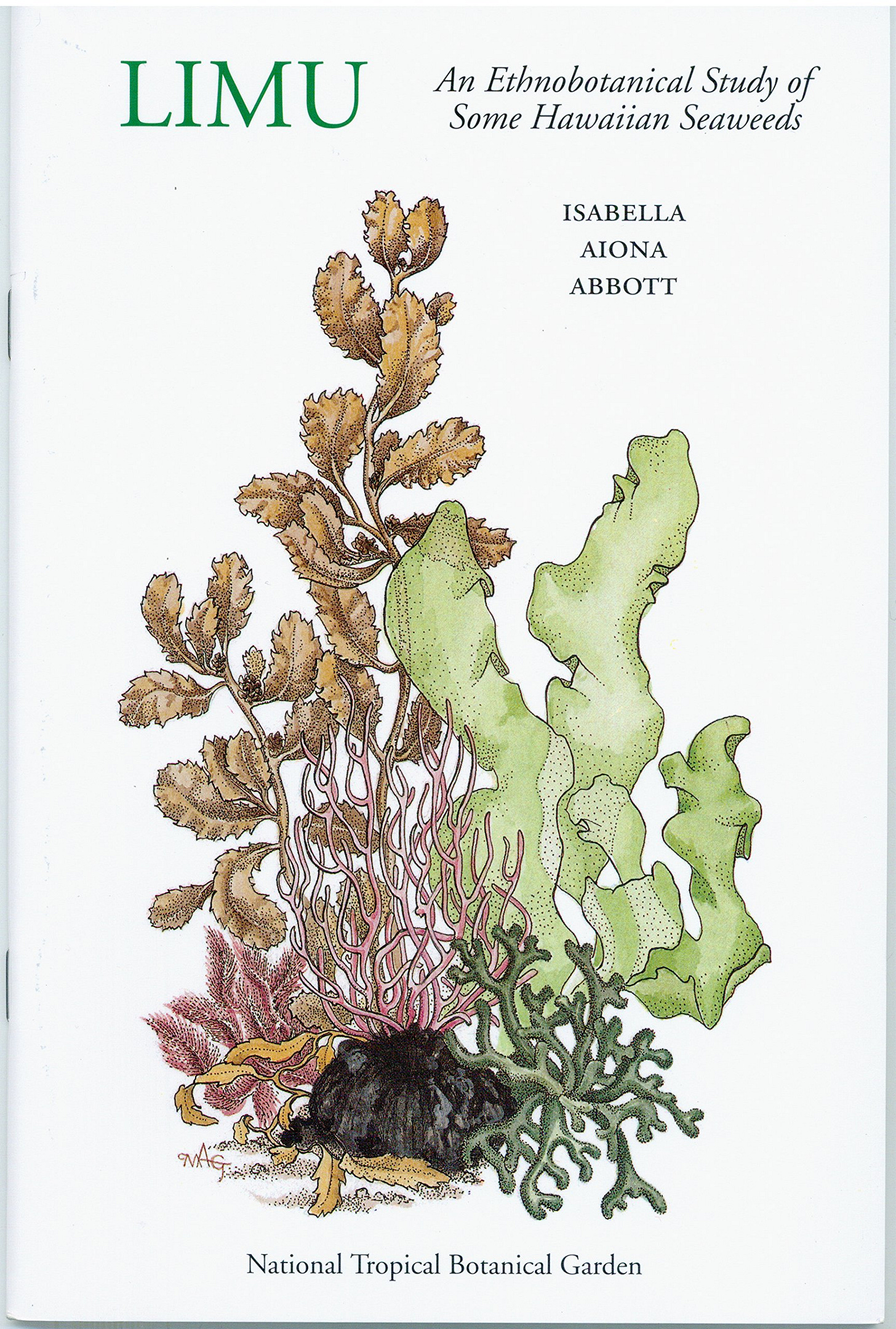

“There [are] thousands of people who work on flowering plants; flowering plants mostly have the same kind of life history, so they become kind of boring,” Dr. Isabella Aiona Abbott sighed. “They make pretty flowers, they make nice smells; they taste good, many of them. But they’re not like seaweeds. Every one you pick up goes through life a different way.”

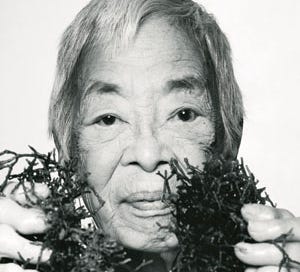

Izzie carved out a space in the under-appreciated world of marine algae, and created a place for both indigenous knowledge and for women of color in Western science. She became the first Native Hawai'ian woman to earn a PhD in science, the first woman and first person of color biology professor at Stanford University, and the world’s foremost expert on Pacific marine plants, discovering over 200 species of algae and authoring eight books and over 150 publications. All of this earned her the moniker “the First Lady of Limu,” limu being the Hawai'ian name for algae. And it all started with her native Hawai'ian mother passing on her traditional knowledge of edible limu.

Born in 1919, Isabella Kauakea Yau Yung Aiona had seven brothers, six of which Isabella's father had brought with him from a previous marriage. He had immigrated from China as a teenager and spent five years working off the cost of his transport at a sugar plantation. Isabella’s childhood was spent exploring the beaches by Ka'alawai and with her mother and younger brother; summers took them to her grandmother’s small beach house in Lahaina. They would wade in the water together searching for seaweed specimens that had drifted in with the tide.

“It wasn’t a big limu place, but it had enough,” Izzie explained. Her mother knew the Hawaiian names and appearance of the roughly 60 native edible limu species: She “never made a mistake. And so when I grew up, I put Latin names with those Hawai'ian names. I never made a mistake either.”

Izzie also learned limu recipes from her mother: “pālahalaha, or sea lettuce, could be eaten fresh but was better in soup. Spongy green wāwa‘iole was ‘ono (delicious) when pounded with raw octopus,” a profile of Izzie noted.

“The women were the ones who knew the Hawaiian names,” Izzie declared. “When … I went around and interviewed different Hawaiian women on each of the islands. … I met a Hawaiian man and I asked him, You know some Hawaiian names of limu? No, he said, go ask my auntie.”

One of the best limu was the species found growing on the rocks in front of Queen Lili'uokalani’s old house: huluhulu waena. Lili'uokalani loved this dark, branching limu so much she had it transplanted from Lahaina to Waikiki in order to cultivate the species on O'ahu. But the most important seaweed in Hawaiʻi is Limu kala.

“People eat it, turtles eat it. And kala means ‘to forgive.’ It’s used in purification ceremonies like ho’oponopono (the Hawaiian reconciliation process), or if you’ve been sitting with a dead person, or if you’re going on a dangerous journey,” Izzie said in an interview.

At her all-girls boarding school, Izzie’s love of plants was further cultivated as the students were required to care for the newly installed lush gardens on campus. She was already a star student: at 14, she represented the school at the junior finals of the Constitution oratorical contest sponsored by the Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

Izzie’s first day of college at the University of Hawai'i was special for many reasons. One of which was that the alphabetical seating arrangement sat her right next to Donald Abbott in botany class. She married Donald after earning her botany bachelor’s in 1941 and master’s in 1942. WWII temporarily derailed Donald’s graduate studies as he was assigned to the Chemical Warfare Service. After the war, the couple moved to California, where they both continued studying. While she contemplated calcified red algae, he pondered sea squirts. Donald finished up his master’s, and then in 1950, they both earned their PhDs at the University of California: his in zoology and hers in botany.

Donald took a job teaching at Stanford University’s spectacular Hopkins Marine Station research laboratory, but nepotism regulations prevented Izzie from securing a post there as well, despite her qualifications. Izzie kept busy taking care of their new baby daughter, Annie, and exploring the beaches and limu species of her new home of Monterey Bay.

“It’s a game; it’s a game. I bet with myself the whole time, from the time I cut it on the outside. I say, Oh, I think this might be in such-and-such a family, or something like that. And by the time I get to some magnification on the microscope, oh, no, you’re hundred percent wrong,” Izzie said. “I love my work. I couldn’t be luckier or happier than what I’m doing now. But, say, if I could go to the beach and not have to run in and look at the algae that are growing at that particular beach, that would be nice.”

Eventually, she was allowed to become a lecturer at Stanford. The Abbotts' little home was a hub for visiting international scientists and students alike. Izzie loved showing off her cooking skills, especially her seaweed recipes. Her bull kelp seaweed cake was legendary—so legendary, Gourmet magazine wrote about it in 1987.

Izzie spent decades without the security of a permanent position at Stanford, despite continuing to publish regularly. In 1969 she won the Darbaker Prize of the Botanical Society of America and published the book Marine Algae of the Monterey Peninsula, California, co-authored with professor George Hollenberg. The text added 55 new species of algae to the record. Hollenberg even named a new genus of red algae after her: “Abbottella,” or little abbott. Izzie was barely 5 feet tall.

In 1972, Izzie was allowed to bypass the tenure track and become a full professor of biology. After a diagnosis of breast cancer, Izzie underwent an extensive mastectomy (really the only treatment available at the time since chemotherapy was just being born) and achieved a full recovery.

The Abbotts retired from Stanford in 1982 and moved back to Hawai'i, but this was far from a true retirement. Izzie became the endowed Wilder Professor of Botany at the University of Hawai'i, where her experiential classes focused on ethnobotany. Her passion for the specialty led the university to create a bachelor’s program in the field. But cancer struck the Abbotts again, and after a long battle, Donald passed away in 1986.

Though beloved among students, Izzie once conceded that there would always be a push-pull between her indigenous knowledge and University education: “some Hawaiians get tired of me sometimes and say, Oh, that’s because she’s a Western scientist.”

“What’s your answer to that?”

“I can’t help it. I was trained that way.”

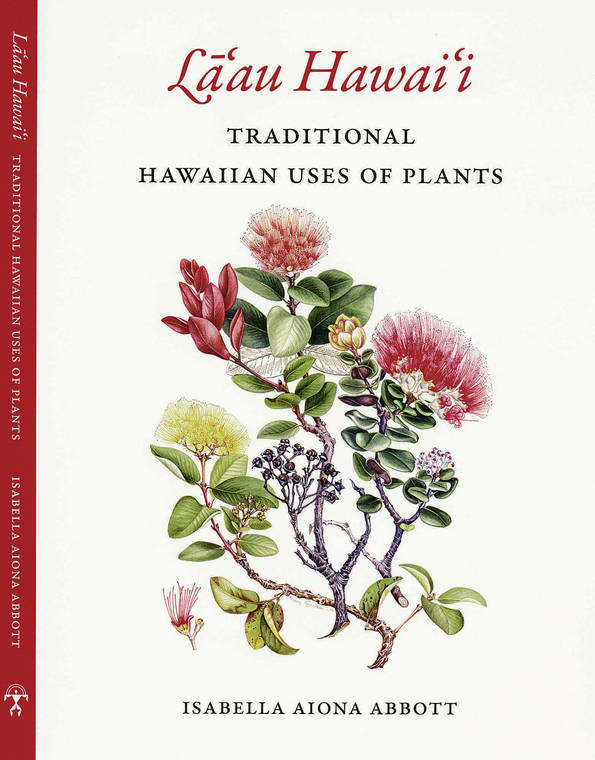

Izzie’s 1992 publication Lā'au Hawai'i: Traditional Hawai'ian Uses of Plants was the people’s first comprehensive ethnobotany textbook. With stunning illustrations and vivid prose, Izzie blended her scientific and indigenous knowledge to tell the history of Hawai'ians’ traditions of making clothing, canoes, and medicine from plants.

“Why is this necessary?” Izzie expounded. “So that Hawaiians are not put in second- or third-class status of native people who don’t know anything. Hawaiian culture is unbelievably sophisticated.”

In 1997, Izzie received the highest honor in marine botany, the Gilbert Morgan Smith medal, from the National Academy of Sciences. Later, she was named a Living Treasure of Hawai’i and bestowed a lifetime achievement award for her work on saving coral reefs. Izzie even got to name an NOAA research ship, which she dubbed “The Hi’ialakai” meaning “embracing or searching the pathways of the sea.”

Izzie’s Hawaiian name means “white rain of Hāna.” She says it's a geological phenomenon named in the same way we’d name a mountain or a river. Her daughter Annie told the Stanford News that the name is a tribute to the “special way the rain comes in from the ocean there, as sort of a white mist.”

In a world where humans increasingly see themselves as somehow separate from nature, Izzie’s unique outlook, born of being both an ethnobotanist and a Native Hawai’ian, could stand to be taken up more widely.

According to a former student, Izzie “defined human relationships to the ‘āina (‘that which feeds’) as part of nature as opposed to outside of it.”

Recipe: Seaweed Cake

Developed using Nereocystis kelp common in California. In Hawaiʻi, Eucheuma from Kāneʻohe Bay or ogo may be used.

Cream well 1 ½ cups salad oil, 2 cups sugar; add 3 eggs, one at a time, beating well after each addition.

Add 2 cups grated carrots, 2 cups grated Eucheuma or 2 cups coursely chopped ogo, 1 cup crushed, drained pineapple, or 1 cup fresh grated coconut.

Sift together 2 ½ cups sifted flour, 1 teaspoon baking soda, 1 teaspoon salt, 1 teaspoon cinnamon. Mix all together.

Add 1 cup walnuts if desired.

Bake in oblong pan or loaf pan at 350 degrees 45-50 minutes.

Serve plain or with buttercream frosting.

Further Reading:

“Hawai‘i’s First Lady of Limu” by Shannon Wianecki, Hana Hou! The Magazine of Hawaiian Airlines. Issue 22.6: December 2019/January 2020.

“Isabella Abbott, world-renowned Stanford algae expert, dies at 91,” by Louis Bergeron. Stanford Report, December 7, 2010.

Video interview: Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox, PBS Hawai‘i

More about me:

Olivia Campbell is a journalist and author specializing in women, history, and science. Her first book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, was published March 2021 by HarperCollins/Park Row Books.

Buy a *signed* hardback copy online at Newtown Bookshop.

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page