Henrietta’s tale is one worthy of Hollywood treatment: as inspiring, titillating, and tragic as any portrait of historical male genius that’s regularly plastered across our screens. Born into a poor family, her intelligence and hard work saw her eventually enjoy a successful career when she took up her father’s mantle of ship propeller engineer. Her work has been hailed as one of the most important nautical inventions in the 19th century. She found happiness outside of her loveless marriage in the form of a passionate 12-year affair with a handsome politician, but died in obscurity in an insane asylum at age 49.

Henrietta Lowe was born in Surrey, England in 1833. She was the fourth of six children. Five years after she was born, her father, a blacksmith and inventor, used all of his wife’s money to purchase a patent for his screw propeller. The ensuing legal battles over copyright infringement left the family destitute.

In 1855, Henrietta married 23-year-old Lieutenant Frederick Vansittart of the 14th Regiment of Light Dragoons. He had recently returned from several years of service in India fighting in the Anglo-Sikh Wars. Henrietta’s tinkering in her father’s workshop likely began at a young age, and her marriage didn’t seem to interrupt this apprenticeship. Vansittart accompanied her father on a test of his screw propellers onboard the HMS Bullfinch in 1857.

Perhaps she preferred the workshop over the boredom of life as a housewife. Or perhaps she just wasn’t very fond of her husband and liked the excuse to be out of the house. No matter her reason, learning at her father’s side was just the thing to engage her incredible mind.

Just a few years after getting married, Henrietta began an affair with well-known novelist and politician Edward Bulwer-Lytton. He was a member of parliament 30 years her senior. Henrietta moved into her grandfather's old house in 1861 and Edward paid her an allowance during her estrangement from her husband.

The affair was intense, with passions running high on both sides. A December 1862 letter from Henrietta to Edward begins: “I cannot bear the suspense of waiting for an answer from you, it is killing me, and I also think I shall die for your letter has given me such a shock that I feel myself gradually sinking under it.”

When her father died after being run over by a carriage, Henrietta picked up where he left off in his refining of propeller technology. Despite his Lowe propeller being fitted to several British warships over the years, the infringement dispute ensured he’d never seen a penny.

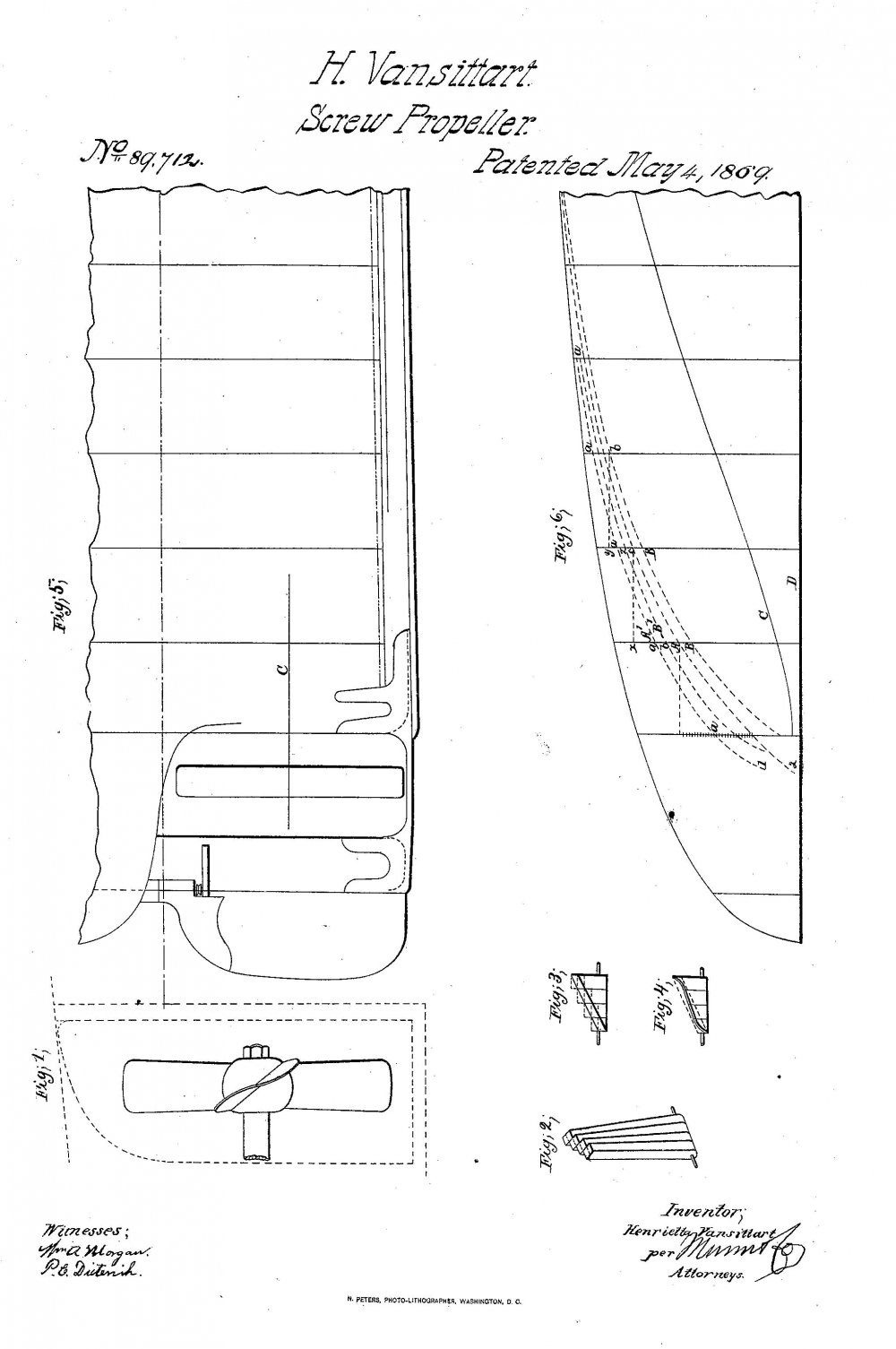

Henrietta proved far more successful, and original, in her invention endeavors than her father. Within two years, she’d already produced a patentable product. On October 8, 1868, the London Gazette announced that Henrietta Vansittart had been granted Patent 2877 for the invention of “improvements in the construction of screw propellers.” She also obtained a US patent. Her Lowe-Vansittart propeller was faster and more efficient than existing propellers. It also produced less vibration and smoother reverse steering.

The government wasted no time in implementing her amazing technology. The Lowe-Vansittart propeller was soon fitted to the HMS Druid, the SS Lusitania, the SS Scandinavian, and several other naval and civil sea vessels.

Henrietta exhibited her patented device under the long-winded name “Lowe-Vansittart Curved line or Three Pitched Wave Line, Non-vibrating, Full body, Economical Screw Propeller.” Over the next decade, it racked up accolade after accolate at international exhibitions showcasing arts and engineering innovations across the globe: a first-class diploma at the 1871 International Exhibition in Kensington, first-class diplomas and medals at exhibitions in Dublin, Paris, Belgium, Naples, Sydney, and Melbourne, a first award of merit and gold medal at the 1881 Adelaide Exhibition.

In 1876, she wrote and illustrated a scientific paper on the Lowe Vansittart screw propeller, and became the first woman to present her own research in front of the London Association of Foreman Engineers and Draughtsman. She presented her work there again in 1880. A long pamphlet followed, The History of the Lowe Vansittart Propeller, which she authored in 1882. It inventoried the contributions she and her father had made to propeller technology. She hoped it would celebrate her father’s work, defend his innovation against criticism, and resurrect him as an important inventor of his time.

Just as her career began to take off, her fiery affair came to a close. Perhaps her busy career of traveling the world presenting her invention left little time for romance, or perhaps it was just that her husband was back from war and her lover got sick. By 1871, Frederick had retired from military service and Edward ended his tumultuous affair with Henrietta after falling ill.

She doesn’t seem to have taken kindly to the ending of the relationship, and couldn’t bear it when he accused her of fearing the loss of his monetary support. On June 5, 1871, Henrietta wrote to Edward: “You are cruel to answer my letter as if its contents contained mercenary feelings; and you need not speak to me about my husband as I do not care a bit about him, neither do I care a jot about money. I did not estrange myself from you; you estranged yourself from me.”

After his death a couple of years later, Edward left Henrietta £1,200. She could not appear at his funeral, but offered her condolences to Edward’s son via letters. (Edward left Frederick £300; a trifling sum for sharing his wife for over a decade!)

At some point during her trip to the North East Coast Exhibition of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering in Tynemouth in September 1882, Henrietta was found wandering the streets, confused and behaving erratically. She was committed to the Tyne City Lunatic Asylum at Coxlodge. Case notes state that when admitted, she was covered in bruises. Her first episode of mania lasted 8 days and she was flagged as a danger to others since she was prone to violence during her episodes. She was also prone to screaming about ‘the devil, the Virgin and God.’ While committed, she contracted an anthrax infection on her skin and developed weeping boils. On February 8, 1883, Henrietta died. The cause of death was listed as acute mania and anthrax infection.

“She was a remarkable personage with a great knowledge of engineering matters and considerable versatility of talent,” her obituary in the Journal of the London Association of Foreman Engineers and Draughtsmen noted. “How cheery and thoughtful for the happiness of others she was.”

Henrietta was a complicated, independent woman who defied the conventions of her time in more ways than one. She was a brilliant engineer who achieved more than many of her well-educated male counterparts, and unrepentantly lived her life on her own terms.

Further Reading:

“Henrietta Vansittart: a business-minded inventor,” Women in Engineering, The Science Museum of London, June 22, 2020.

“The Long Read: Discovering the Victorian Engineer Henrietta Vansittart, part 1,” by Emily Rees Koerner, Electrifying Women, January 27, 2020.

More about me:

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page

Pre-order my book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, out March 2, 2021 from HarperCollins/Park Row Books.