Not all women in the Regency era whiled their days away pining for a man to come whisk them off into the sunset. Some women were busy reading all they could about mathematics.

At her childhood home in Fife, Scotland, young Mary Fairfax (born in 1780) spent her days exploring the vast gardens where her mother grew vegetables to supplement her husband’s meager military salary. Her father was away with the navy for nearly the first decade of her life. When he returned home, he was “shocked to find such a savage” and sent her off to boarding school to learn to read and write.

But a love of the natural world had already been firmly ingrained. Once back at home, she began venturing beyond the garden: “When the tide was out I spent hours on the sands, looking at the star-fish and sea-urchins, or watching the children digging for sand-eels, cockles, and the spouting razor-fish. I made collections of shells… There was a small pier on the sands for shipping limestone brought from the coal mines inland. I was astonished to see the surface of these blocks of stone covered with beautiful impressions of what seemed to be leaves; how they got there I could not imagine, but I picked up the broken bits, and even large pieces, and brought them to my repository.”

Mary’s sense of women’s unjust position in society was also formed quite early on, as was her belief in the cruelty of slavery. She and her brother both refused sugar in their tea due to the use of slave labor in its production. Mary was thoroughly annoyed by her relatives’ disapproval of her spending her time reading books, which saw her sent to learn the more-feminine activity of needlework.

“From my earliest years my mind revolved against oppression and tyranny, and I resented the injustice of the world in denying all those privileges of education to my sex which were so lavishly bestowed on men,” Mary wrote. Other aunts and uncles proved more helpful, opening their libraries to her, tutoring her in Latin, introducing her to soon-to-be-famous geologist Charles Lyell.

One afternoon at a tea party, teenage Mary was offered a ladies' fashion magazine, which contained a puzzle. The answer contained strange symbols, which turned out to be algebra. She was hooked. Mary sought out and capitalized on any and every opportunity to learn: algebra, geometry, Euclid, Greek, even becoming an unofficial student to her brother’s tutor.

Mary grew into a beautiful slip of a woman with smiling eyes and curly, light-brown hair; shy, but self-possessed. Her small frame and soft voice belied her charm and energy. Most of all, she had an ardent, lifelong thirst for knowledge.

1804 brought a marriage and a move to London. It was an unhappy marriage to a distant cousin who frowned upon the concept of learned women. Mary birthed two children in quick succession, before her husband died suddenly in 1807. She then took her babies back to her Scottish home.

The marriage did have one silver lining: the money her husband left behind ensured she could continue her studies without worrying about supporting her family. She immersed herself in trigonometry, James Ferguson's Astronomy, Isaac Newton's Principia, and modern French mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace’s work on gravity. She began a lively correspondence on mathematics with Scottish mathematician and astronomer William Wallace. Mary solved math problems put forward by mathematics journals. For solving a diophantine problem, she was awarded a silver medal in 1811. Under the unimaginative pseudonym ‘A Lady,’ five of her solutions were published in Mathematical Repository. Her use of differential calculus was revolutionary.

In 1812, at age 32, she married yet another cousin, Dr. William Somerville, and returned to London. He was inspector of the Army Medical Board, and proved much more encouraging in Mary’s studies than her previous husband. Her interests widened to include other topics: astronomy, magnetism, chemistry, geography, microscopy, electricity. A year into her marriage she rewarded herself with a library of scientific books on mechanics, analytical function, algebra, calculus, geometry, astronomy, geography.

After William was elected to the Royal Society, the couple entered the social circle of Britain’s leading intellectual luminaries, many of whom were also scientist-couples. Mary now counted among her friends chemists and science writers Alexander and Jane Marcet, geologists Charlotte and Roderick Impey Murchison, polymath Thomas Young and his wife Eliza, the Herschels, Faraday, painter J.M.W. Turner, and writer Walter Scott. Mary was a frequent visitor to Charles Babbage’s home, where she observed his creation of “calculating machines” with great interest.

“I shall never forget the charm of this little society, especially the supper-parties at Abbotsford, when Scott was in the highest glee, telling amusing tales, ancient legends, ghost and witch stories,” Mary recalled. Mary herself was a skilled piano player and painter.

But gatherings weren’t just about music, merriment, and tall tales. Mary and William once spent all night at Henry and Mary Frances Kater’s home, the four of them testing the power of their telescope by seeing what they could observe of double stars. On their way home in the wee hours of the morning, the Somervilles happened to notice that their friend Thomas Young’s light was on, so they rang his bell. Young excitedly invited them in to view the ancient Egyptian papyrus he had just determined was a horoscope.

Mary was also cozy with Anne Isabella Milbanke, Baroness Wentworth, whose daughter she tutored in mathematics: Ada Lovelace. Mary took Ada to scientific gatherings, where she introduced her to Babbage. It was an introduction that would prove vital to the future of scientific advancement: Ada and Charles went on to create the world’s first computer together. Mary and Ada’s friendship also endured, thanks to their shared passion for mathematics. Whenever Ada found herself stumped by a math problem, she would write to her mentor, Mary.

William and Mary Somerville were participants, and often hosts, of larger scientific salons: “Somerville and I used frequently to spend the evening with Captain and Mrs. Kater. Dr. Wollaston, Dr. Young, and others were generally of the party; sometimes we had music, for Captain and Mrs. Kater sang very prettily. All kinds of scientific subjects were discussed, experiments tried and astronomical observations made in a little garden in front of the house,” Mary explained.

Most intriguing of all were Mary’s salons held just for women, where topics of discussion ranged from science and literature to solving social ills of the day. So many wives of these intellectuals were also incredible thinkers in their own right; when they got together, the conversation must have been positively electric.

In addition to their vast library, the Somervilles kept a large cabinet of exquisite mineral specimens. “It was a great amusement to arrange the minerals we had collected during our journey. Our cabinet was now very rich,” Mary mused. “With crystals of sapphire, ruby, oriental topaz, amethyst.” Within walking distance of the Somervilles’ home was the Royal Institution, where subscribers could attend lectures in topics like mechanics, chemistry, and botany. Surprisingly, women were welcome. Mary attended lectures often, frequently accompanied by her husband. The Somervilles had four children together, though their only son died in infancy and their youngest daughter fell ill and died in 1823 at the age of 10.

Mary represents the pinnacle of the Amateur Scientist era, a time when people went into the study of science purely for the love of it, not for the money. There wasn’t much money to be made in being a scientist at the time; many scientific societies required paying dues, so science was often reserved for those with the financial independence to dabble in whatever piqued their curiosity, not what brought in a steady income.

It was an era that prized accessibility over jargon in science texts; expertise in the form of self-guided study and experimentation was as welcome in scientific circles as traditional education. This was particularly advantageous for women, who were not yet welcome in traditional educational settings. Still, women of this era largely gained access to science training and collaborators via a scientist husband, father, or brother.

Mary’s first credited publication came as a result of her experiments with the relationship between light and magnetism. “The magnetic properties of the violet rays of the solar spectrum,” appeared in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society in 1826. Subsequently, she was asked to translate Pierre-Simon Laplace’s Traite de Mecanique Celeste for The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. The result was more like an annotated translation. In addition to the original text, Mary had included her own explanations in layman’s terms, real-world context, historical background information, and illustrations.

Laplace declared Mary the only woman to understand his work. Most male mathematicians in Britain could only dream of receiving such approval. The Mechanism of the Heavens became a go-to math text at the University of Cambridge. Praise kept rolling in: “The great simplicity of your manner of writing ... particularly suits the scientific sublime. You trust sufficiently to the natural interest of your subject, to the importance of the facts, the beauty of the whole,” raved Mary’s friend, novelist Maria Edgeworth. David Brewster, inventor of the kaleidoscope, proclaimed Mary “certainly the most extraordinary woman in Europe - a mathematician of the very first rank with all the gentleness of a woman.” She had become a sensation.

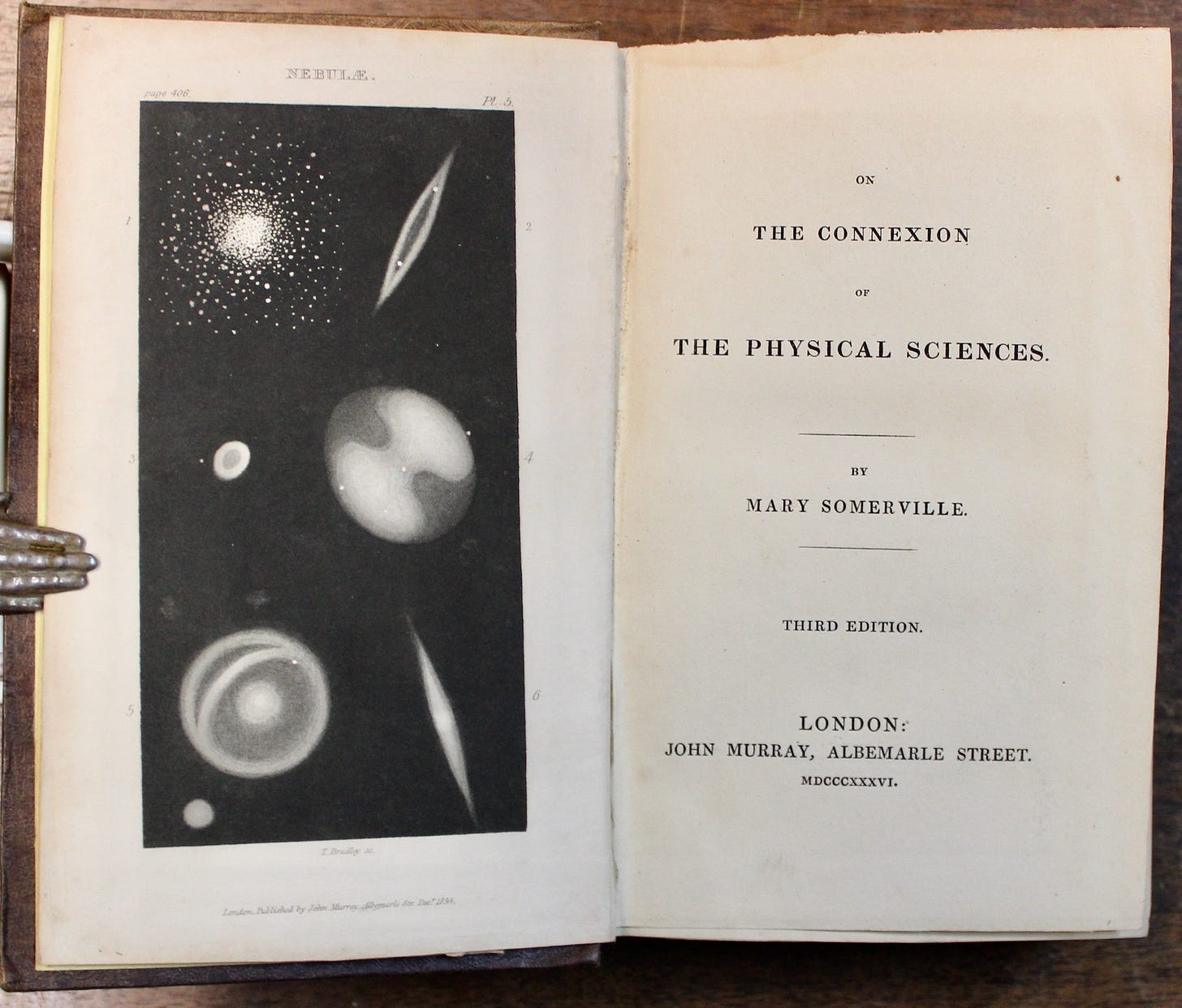

Her subsequent books were both well-received and widely read by academics and lay audiences alike. On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences was published in 1834 and sold 15,000 copies. Critics and scholars lauded it as an easy-to-understand survey of astronomy, chemistry, and physics. The book formed the foundation of modern physics as we know it. Mary loved how astronomy was a convergence of all other sciences: “we perceive the operation of a force which is mixed up with everything that exists in the heavens or on earth; which pervades every atom, rules the motions of animate and inanimate beings, and is as sensible in the descent of a rain-drop as in the falls of Niagara; in the weight of the air, as in the periods of the moon.”

In a review of Connexion, philosopher William Whewell coined the term “scientist” to describe “students of the knowledge of the material world collectively.” Thus Mary is referred to as the very first “scientist.”

Next came Physical Geography, which sold even more copies than the last, won Mary the Victoria Gold Medal of the Royal Geographical Society, and was used as a textbook until the early 20th century.

In 1835, Mary Somerville and Caroline Herschel became the first women members of the Royal Astronomical Society. In 1842, a marble bust of Mary was put on display in the Royal Society’s Great Hall. The Royal Society was founded in 1660, but women wouldn’t be allowed to become fellows until 1945. So during Mary’s life, her bust was allowed in the Society, but she was not.

It was lucky that Mary’s books did so well, since the family really needed the money she was making. The Somervilles’ increasing financial problems saw them move to Italy, where the cost of living was much lower. Mary’s fight for women’s equality continued into her old age. In 1868, her signature was first on the Parliamentary petition requesting the right to vote be extended to women. Molecular and Microscopic Science was Mary’s fourth and final book, published when she was 89 years old.

At the end of April 1872, at the age of 91, Mary went on one final research adventure, winding down her life in the same way as it began: exploring the natural world in person. This was her actually the second time she and her daughters had gone to see the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

Vesuvius was now in the fiercest eruption, such as has not occurred in the memory of this generation, lava overflowing the principal crater and running in all directions. The fiery glow of lava is not very visible by daylight; smoke and steam is sent off which rises white as snow, or rather as frosted silver, and the mouth of the great crater was white with the lava pouring over it. New craters had burst out the preceding night, at the very time I was admiring the beauty of the eruption, little dreaming that, of many people who had gone up that night to the Atrio del Cavallo to see the lava (as my daughters had done repeatedly and especially during the great eruption of 1868), some forty or fifty had been on the very spot where the new crater burst out, and perished, scorched to death by the fiery vapours which eddied from the fearful chasm. Some were rescued who had been less near to the chasm, but of these none eventually recovered.

Behind the cone rose an immense column of dense black smoke to more than four times the height of the mountain, and spread out at the summit horizontally, like a pine tree, above the silvery stream which poured forth in volumes. There were constant bursts of fiery projectiles, shooting to an immense height into the black column of smoke, and tinging it with a lurid red colour. The fearful roaring and thundering never ceased for one moment, and the house shook with the concussion of the air.

One stream of lava flowed towards Torre del Greco, but luckily stopped before it reached the cultivated fields; others, and the most dangerous ones, since some of them came from the new craters, poured down the Atrio del Cavallo, and dividing before reaching the Observatory flowed to the right and to the left - the stream which flowed to the north very soon reached the plain, and before night came on had partially destroyed the small town of Massa di Somma.

She died in November of that year. “Whatever difficulty we might experience in the middle of the nineteenth century in choosing a king of science, there could be no question whatever as to the queen of science,” her obituary declared.

Further Reading:

“Mary Somerville’s Vision of Science,” by James Secord. January 2018, Physics Today.

“Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary,” by Brigitte Stenhouse. March 2021, Math Intelligencer.

“Celebrating Mary Somerville,” by Robyn Arianrhod. Cosmos Magazine.

More about me:

Olivia Campbell is a journalist and author specializing in women, history, and science. Her first book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, was published March 2021 by HarperCollins/Park Row Books.

Buy a *signed* hardback copy online at Newtown Bookshop.

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page