The Radical Inclusivity of Early Women's Medical Schools

Empowered with MDs, women of color often helped their own communities.

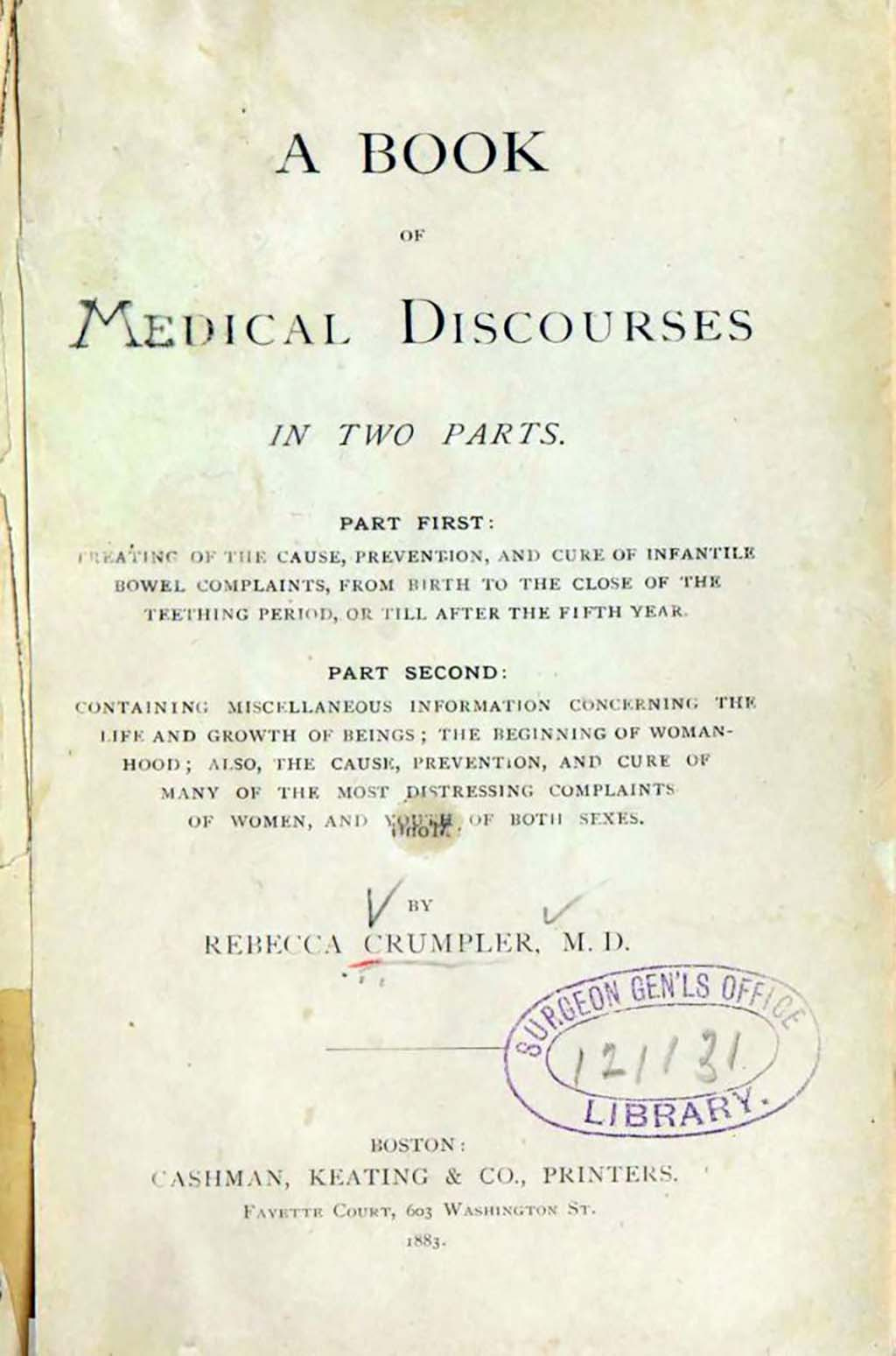

America’s early women’s medical schools were truly radical: they admitted women of all races, nationalities, and ethnicities. When Sarah Mapps Douglass enrolled at the Female Medical College of Pennsylvania in 1853, she became the first Black woman medical student in the U.S. (The college had only existed for three years.) At the time, only three Black men had earned medical degrees in America. In 1864, Rebecca Lee Crumpler became the first practicing Black woman MD in the US after graduating from the New England Female Medical College.

All of these firsts happened before the abolition of slavery in America. And they largely only happened because of the inclusivity of women’s medical schools.

Medicine was one of the first sciences American women demanded entrance into. Women knew there was a need for healthcare delivered by women, for women. Since they were not welcome at hardly any established medical schools, separate schools just for women were founded. It was (and remains) especially important for patients of different racial and ethnic groups to see themselves in their physicians. In other words, for example, Black women doctors have unique insights into the lives and experiences of their Black women patients, in a way no white man doctor could ever hope to approximate.

Quite the opposite, in fact. Medical racism ran rampant in antebellum America. At the same time that women’s medical schools and hospitals in the northern states were welcoming women of color as students, interns, colleagues, and patients, the false belief that Black people were biologically inferior was still firmly entrenched in the sciences. Among these pervasive beliefs was that Black people were less intelligent and felt less pain. Women were also considered inferior to men. In the 1840s, J. Marion Simms was performing barbaric anesthesia-less surgeries on enslaved Black women. He tortured them for years to “perfect” his gynecological procedures. But when Simms began treating white women, he used anesthesia.

That’s what I mean when I say admitting women of color to medical schools was a radical act at the time: while they were treated as practically inhuman in some areas of the country, to be welcomed as equals—as women, in science education no less—was truly revolutionary.

These women overcame the dual mountains of sexism AND racism in their fight to earn medical degrees. Unfortunately, having an MD didn’t render them immune from prejudice. They encountered intense racism and sexism while practicing medicine, too. Most were unable to find jobs at already-established hospitals. Instead, these women used their medical degrees to transform the health of their own communities.

Douglass, an accomplished educator, active abolitionist, and talented artist, had been teaching for several decades when she merged her girls’ school into Philadelphia’s Institute for Colored Youth. Her love of science (especially mineralogy, botany, and anatomy) inspired many of her students. After taking courses at the women’s medical college, Douglass began offering evening lectures to Black women on physiology and anatomy. She delivered these lectures for many years, in Philadelphia and New York, hoping that by empowering women with knowledge of how their bodies worked, they could gain some control over their reproductive lives. She also encouraged her audience to push back against assertions of race-based biological differences.

After the Civil War, Crumpler treated patients at the Freedmen's Bureau in Richmond, Virginia. The institute provided medical care to formerly enslaved people who had been denied care by white physicians. It also offered food, housing, education, and legal assistance.

In 1867, Rebecca J. Cole became the second Black woman in the U.S. to receive an M.D. degree when she graduated from Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP) (The Female Medical College of Pennsylvania changed its name in 1867). Cole was a former student of Douglass’s: evidence of the power of mentoring and the importance of introducing girls to the wonders of science.

After working with Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell at their New York Infirmary for Women and Children, Cole returned to her hometown of Philadelphia and opened a center where poor women and children could obtain medical and legal services. She was later appointed superintendent of a home run by the Association for the Relief of Destitute Colored Women and Children in Washington, D.C.

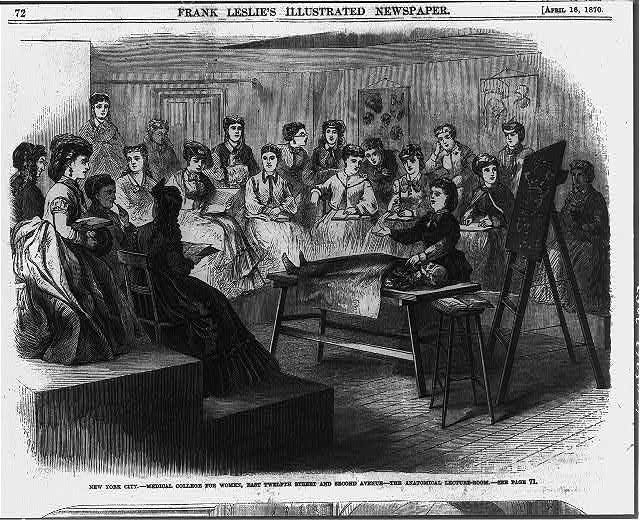

"[E]very face is a more or less … as they appeared, intent upon the lecture,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper noted in its April 16, 1870 article on the college. “Among them will be noticed the dark-skinned, but intelligent and intellectual features of the young lady who graduated during the past month, and who, in addition to other distinctions, possesses that of being the first colored female graduated doctoress in America, or perhaps the world."

Like Douglass, Cole fought medical and scientific racism. In response to W.E.B. DuBois’s assertion that the high incidence of tuberculosis among Black people post-Civil War was due to their ignorance of basic hygiene, Cole countered that their suffering was actually attributable to white physicians refusing to treat them or treating them poorly. She insisted it was housing discrimination that saw Black people relegated to living conditions that were breeding grounds for contagious illnesses.

In The Women’s Era, Cole declared “the poor are attended by young, inexperienced white physicians. … We must attack the system of overcrowding in the poorer districts … that people may not be crowded together like cattle, while soulless landlords collect 50 percent on their investments.”

Women from other marginalized groups also found a warm welcome at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania.

As a young girl, Native American Susan La Flesche decided to pursue medicine after watching a sick woman in her community die because the local white doctor refused to treat her. When she graduated from the WMCP at the top of her class in 1889, she became the first Native American to receive an MD. She returned to her Omaha reservation, where she served 1,300 patients over 450 square miles, and later opened a hospital.

Sarah Cohen May was only 21 when she graduated from the WMCP. The daughter of impoverished Orthodox Jewish immigrants, she also brought her newfound medical knowledge to the aid of her own people. She was the only Jewish woman physician in Philadelphia, and likely the only one who knew the language, social customs, and childbirth rituals of the Orthodox community. Her practice thrived, and so did her patients.

Anandi Gopal Joshi, Kei Okami, and Tabat Islambouli were the first Indian woman, the second Japanese woman, and the first Syrian woman, respectively, to earn western medical degrees—all three from the WMCP. Joshi’s interest in medicine was sparked by her experience of losing her first child in childbirth. She became an icon in her home country, with a novel and a play written about her life.

Opening the doors of medical education to them meant these women could provide much-needed culturally competent women’s medical care.

NOTE: I found several images labeled as “Rebecca J. Cole”—none of which were actually Cole. Photos of physician Eliza Grier and educator Nannie Helen Burroughs are all being passed off as Cole. A photo claiming to be Rebecca Lee Crumpler is actually the first Black woman nurse in the US, Mary Eliza Mahoney. It’s natural to want to know what historical figures look like, but we have to be very careful that that desire doesn’t lead us to perpetuating misidentification.

For more on this, see the Drexel University Legacy Center Archives & Special Collections blog post: “Is that Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler? Misidentification, copyright, and pesky historical details,” by Matt Herbison.

Further Reading:

“The Woman Who Challenged the Idea that Black Communities Were Destined for Disease: A physician and activist, Rebecca J. Cole became a leading voice in medical social services,” by Leila McNeill, Smithsonian Magazine, June 5, 2018.

“Celebrating Rebecca Lee Crumpler, first African-American woman physician,” by Howard Markel, PBS News Hour, Mar 9, 2016.

“Black History Month: A Medical Perspective: Education,” Duke University Medical Center Library & Archives, last updated February 14, 2021.

More About Me:

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page

Order my book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, published March 2021 from HarperCollins/Park Row Books. Paperback coming soon—March 2022!

Buy a *signed* hardback copy online at Newtown Bookshop.