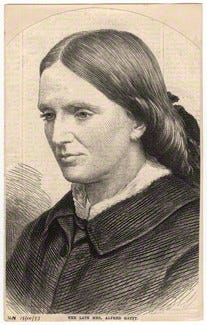

The Seaweed Queen of Sheffield

How Margaret Gatty survived ten pregnancies to become a prolific collector and cataloger of seaweed.

It was the sixth pregnancy and birth that finally broke her. It was her sixth in six years, after all; more than most bodies are created to withstand. (The weaker sex, my butt.) Not enough time in between pregnancies to fully recover, for her body to replenish itself before yet another fetus started stealing her resources. And though her third child had not survived his first year, that didn’t mean the pregnancy had taken any less of a toll on her body.

Margaret Gatty was fading. Each pregnancy stole a little more of her. Today, scholars suspect she was experiencing undiagnosed multiple sclerosis and depression. At the time, it was likely seen as merely a nervous condition. (MS wasn’t identified until 1868.) But she wouldn’t let these defeat her just yet.

The cure of the era for such ailments was saltwater and sea air. At least it was a better option than leeches and/or purgatives. In 1848, with the goal of healing and recovery, Margaret traveled from her home in Ecclesfield (near Sheffield in South Yorkshire) to the seaside town of Hastings, Sussex. She would spend seven months there. This turned out to be an incredibly fortuitous place for recuperation—not only because it allowed her to rest and experience the longest stretch of time not pregnant than she had enjoyed in years—but because she discovered her passion: the intricate beauty and variety of seaweed.

While Margaret knew of marine biology from her second cousin, Charles Henry Gatty of the Royal Society, on the beaches of Hastings, she met William Henry Harvey, an Irish botanist and phycologist specializing in algae. Before long, Margaret struck up a correspondence with several eminent scientists, such as Scottish physician and naturalist George Johnston, Scottish botanist Robert Brown, and George Busk, who practiced surgery, zoology, and paleontology. She also became Harvey’s assistant.

Unfortunately, Margaret couldn’t afford much to encourage her new interest; her husband was a vicar and they had so, so many mouths to feed. A good microscope and specialty science books on algae and seaweed were out of the question. She had to make do with borrowed books and proof-plates shared by Harvey. Margaret collected as many specimens of different seaweed varieties as she could find, bringing any notable finds to the attention of Harvey. She showed amateur collectors—her “seaweed pupils”—how to identify and preserve their treasures.

By the 1851 census, Margaret was listed as both a clergyman’s wife and an algologist. It was not only unusual for a married woman to have a career listed in such a document, it was an unusual career for a woman full stop.

Despite her work and bouts of ill health, Margaret continued to have children. After her first visit to the seaside, she endured four further pregnancies. Thankfully, her physician/naturalist friend George Johnston was a trailblazer in his endorsement of pain relief medication. In 1851, Margaret became the first woman in Sheffield to use chloroform during childbirth. Margaret’s poor health also made her instrumental in bringing the village of Ecclesfield its very own doctor. She convinced Dr. J.H. Aveling to take the position. He tended to Margaret’s final birth in 1855. Sadly, her tenth and final child did not survive infancy.

Margaret supplemented the family’s income by writing books for children. These books used stories from the natural world to teach children lessons in Christian morality. In Parables From Nature, for instance, Margaret combined her interest in promoting science education and her interest in promoting the Gospel. She also argued against Charles Darwin's theories, which she saw as going against God.

The Parables were several series: the first series was published in 1855, the second in 1857; Margaret authored and illustrated both of these. The third series appeared in 1861 with her oldest children, Juliana and Margaret, supplying the illustrations. A fourth series was published in 1864, and a fifth in 1871. She hoped to offer children (and their parents) another vision of nature, one where, unlike Darwin’s, it was created by God.

For many of these publications, she requested to be paid not in money, but in books by Dr. George Johnston.

But Margaret wasn’t only penning work aimed at children. In 1857, she published a letter to the editor, ‘New localities for rare plants and zoophytes,’ in the science journal The Annals and Magazine of Natural History after taking a research trip to the Isle of Wight. She also started a book project, an introductory guide to algology and its terminology for beginners that she hoped would help amateurs better understand more complicated texts on seaweed. Sadly, this project never made it to publication despite being fully written.

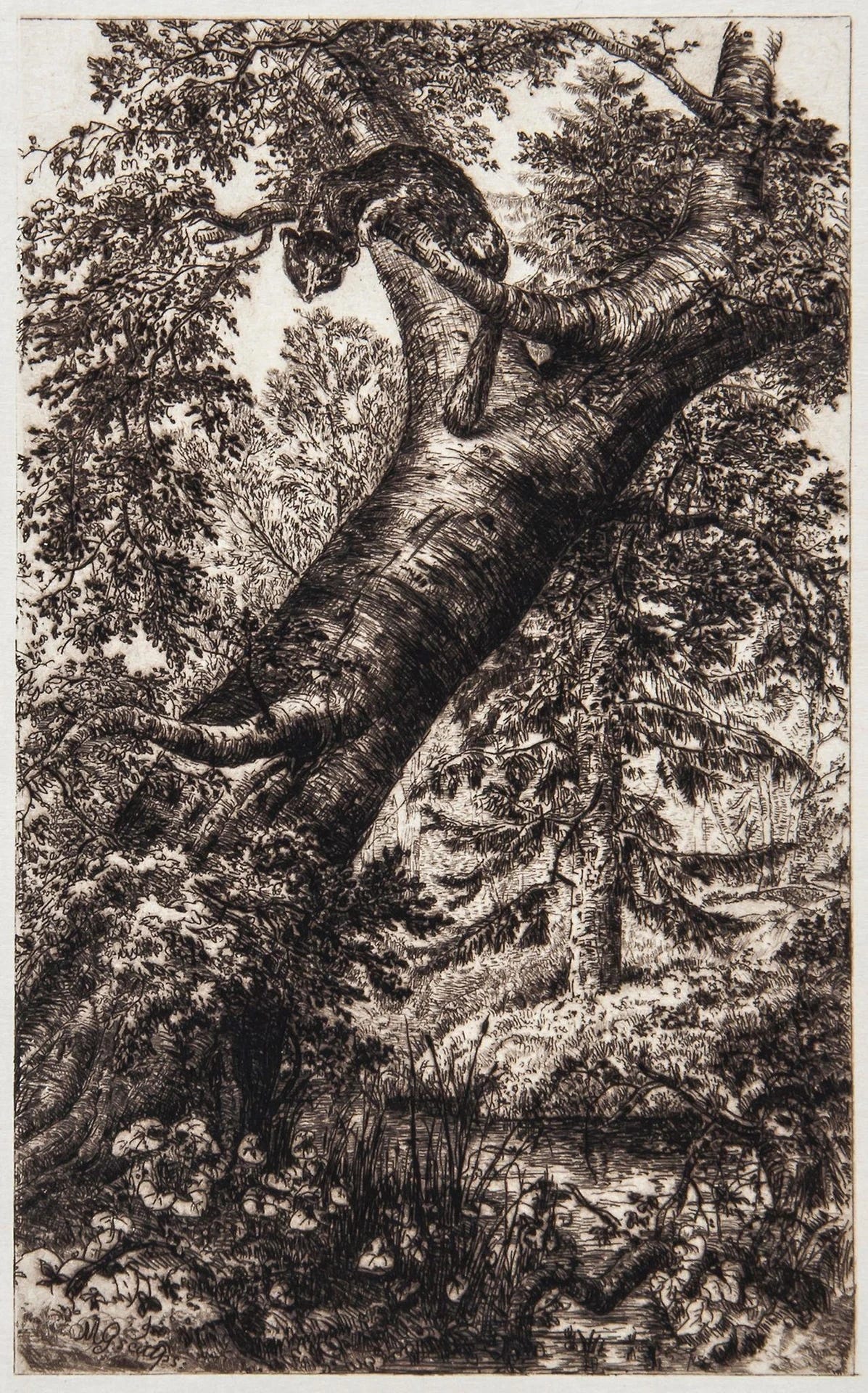

The incredible adult science book she did publish was British Sea-Weeds. It rendered the topic significantly more understandable than any previous text had ever dared. The book was published in two volumes, in 1863 and 1872, and continued to be utilized until the 1950s. It was the culmination of 14 years spent collecting hundreds of species from across the country, featuring beautiful illustrations—86 color plates in all—and describing 200 seaweed species using simple terms. It included an identification key, suggestions for how to arrange your collection in an herbarium, as well as practical advice on what to wear when when specimen hunting, such as petticoats that stopped above the ankle.

“…petticoats; if anything could excuse a woman for imitating the costume of a man it would be what she suffers as a sea-weed collector from those necessary draperies!” Margaret proclaimed. She also noted how free it felt to scamper across the beach.

“Feel all the luxury of not having to be afraid of your boots; neither of wetting nor destroying them. Feel all the comfort of walking steadily forward, the very strength of the soles making you tread firm—confident in yourself, and let me add, in your dress.”

In between volumes, Margaret established the children’s periodical Aunt Judy's Magazine, named after her daughter Juliana. The magazine ran from 1866 to 1885, with Margaret’s daughter Horatia taking over as editor after Margaret died in 1873. Famous writers like Lewis Carroll and Hans Christian Anderson contributed stories on several occasions.

Margaret’s massive collection of marine flora and fauna, which was collected mostly by her, but also by people across the British Empire that she’d tasked with gathering new specimens, is now housed at St Andrews University Herbarium in its Botanic Garden. Margaret has several taxa of marine life named after her, and her daughter Horatia went on to become a specialist in marine invertebrates.

How Margaret managed to accomplish so much in her lifetime while raising eight children and experiencing chronic illness is beyond impressive. Her curiosity and insistence on using plain language to make science accessible, and inspired a love of nature, particularly marine life, in generations of children and adults alike.

Further Reading

“The Forgotten Victorian Craze for Collecting Seaweed,” by Cara Giaimo, Atlas Obscura, November 14, 2016.

“Stunning Drawings of Seaweed from a Book by Self-Taught Victorian Marine Biologist Margaret Gatty,” by Maria Popova, The Marginalian.

“Margaret Gatty – Victorian author and seaweed collector,” by Kateryna Sydorova, Botanics Stories, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh.

More About Me

Olivia Campbell is the author of the New York Times bestseller Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine and a health editor at Dotdash Meredith. Her work has appeared in National Geographic, The Atlantic, The Guardian, Washington Post, New York Magazine, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, and HISTORY, among others. She lives outside Philadelphia with her husband, sons, and cats. Find out more about her life and work on her website.

Buy her book on Bookshop.org, Amazon, or grab a *signed* hardback copy online via her local independent bookstore, Newtown Bookshop.