Victorian Women Doctors: Far From the First

On not perpetuating erasure while attempting to undo it.

My book, Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, tells the story of three women who become the first licensed women medical practitioners in the US, England, and Scotland, respectively. But they were in no way the first women to practice medicine. In my attempt to undo the systematic erasure of women in sciences, I run the risk of erasing all those who came before them.

Contrary to popular belief, Elizabeth Blackwell wasn’t the first woman in the world to earn a medical degree and become a licensed physician. German Dorothea Erxleben beat her to the punch by 95 years. When Dorothea’s father died in 1747, she took over his medical practice. She earned a medical degree in 1754 after receiving permission from King Frederick the Great to attend the University of Halle. (She finished writing her dissertation eight months after the birth of her last child.)

Yet, it was a hollow victory. Once Dorothea proved women were capable of excelling at medical school, they were barred from admission. It would be more than 150 years before another woman in Germany received a medical degree.

The truth is that women have been practicing medicine since the dawn of time.

Whether diviners, herbalists, or surgeons, women have always worked as traditional healers in African countries; medicine women are the norm in the West African society of Tuareg. Mayan women healers came to be known as powerful sorceresses who had extensive knowledge of the body. Tabiba, Arabic for women doctors, played a key role in the Ottoman Empire. Nuns delivered healthcare in the early middle ages, tending herb gardens and nursing injured soldiers back to health. By the early modern era, women were expected to know how to make medicines and care for their families.

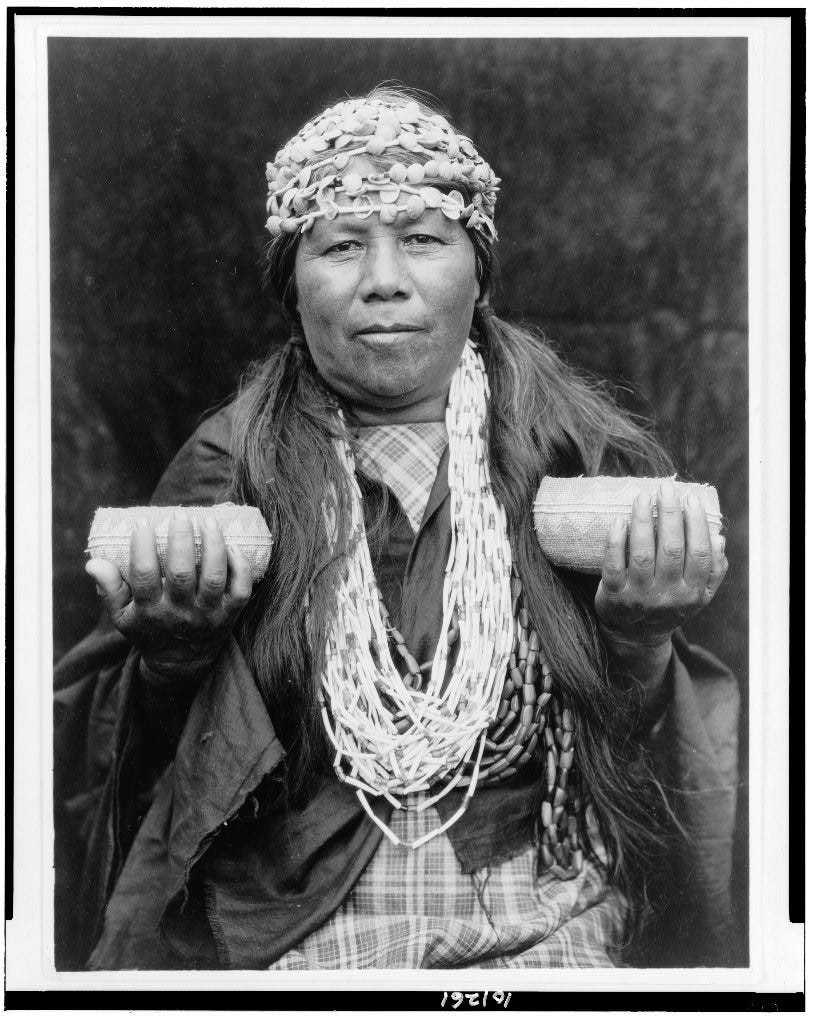

Contrary to popular belief, women have always been involved in the healing art of shamanism in countries and cultures across the globe: in most East Asian cultures and Native American tribes, the Inuit of Canada, several Turkish ethnic groups, indigenous Siberian cultures. Among the San of South Africa, the women healer shaman are considered more powerful than the men.

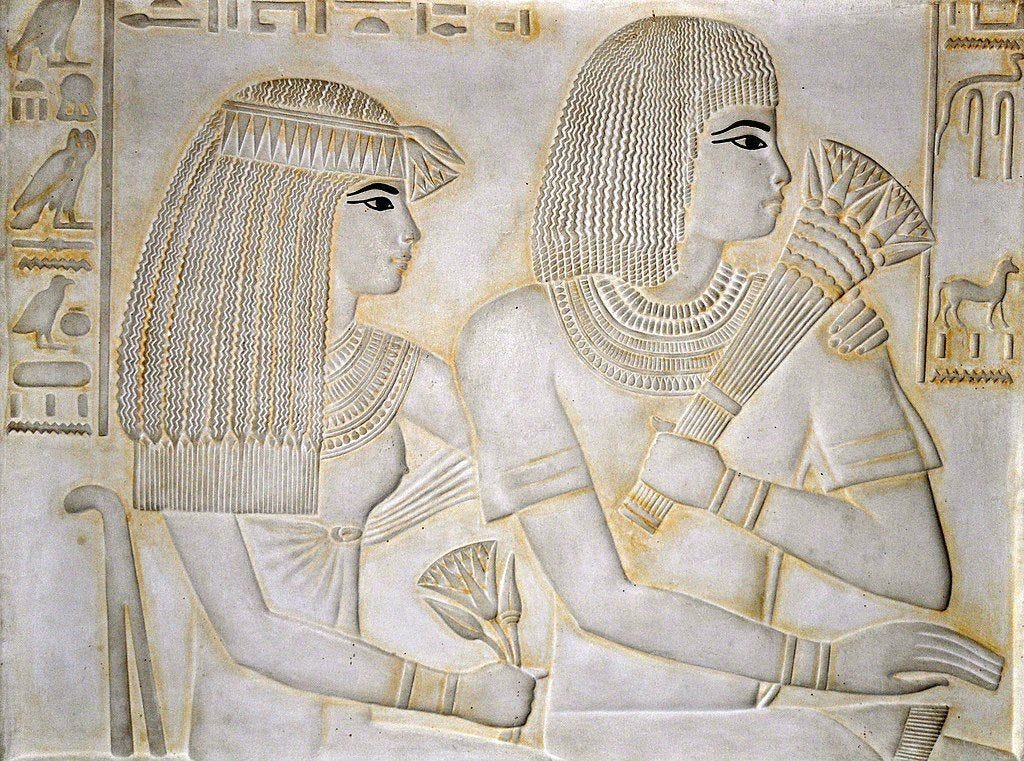

As far back as 3000 BCE, Egypt had a medical school for women specializing in obstetrics and gynecology that was run by a woman. Peseshet served as the Overseer of Women Physicians. Queen Hatshepsut once dispatched an expedition to find new medicinal botanicals.

Aspasia pioneered the field of obstetrics in 400s BCE Athens and Rome and authored the go-to text on gynecology of the time. To prevent miscarriage, she advised her patients not to engage in vigorous exercise or excessive worrying, not to eat spicy foods or carry heavy loads, and to avoid riding in chariots, especially on rough roads. If a pregnancy threatened the mother’s life, she would provide a chemical or surgical abortion. Her innovative surgical techniques and unsurpassed knowledge proved a great influence on future practitioners in the field. Prominent 6th-century male physician and surgeon Aetius of Amida revered Aspasia as medical genius whose talent and skill equaled or even surpassed that of the best male surgeons of her time.

Even Hippocrates, known as the father of Western medicine, acknowledged the importance of women healers and herbalists in 5th century BCE. He mentions Artemisia, queen of Caria, who had a prodigious knowledge of medicinal botanicals. A collection of surviving tombstone inscriptions tells us at least a few women identified as physicians in the first and second centuries in Greece. The texts of early Roman physician Pliny and Greek surgeon Galen reference multiple skilled female healers: Lais of Athens, Olympia of Thebes, Anyte of Epidaurus, Salpe of Lemnos, Elephantis, Lais, Favilla, and Sotina.

In the first century CE, Emperor Claudius’s court physician wrote of an “honest matron” he encountered who cured several patients of their epilepsy with an “absurd” remedy. He also describes a book of prescriptions that had been authored by Octavia, eldest sister of emperor Augustus and scorned wife of Mark Antony. To draw out animal poisons, she suggested a plaster made of wild fig milk, blood and brain fat from a dog, orris root, ammonia, wax, oil, onions, and turpentine. Other salves of her creation include those to treat soreness, toothache, sore throat, and labor pain. Notably absent from Octavia’s concoctions were the foul ingredients of dung and entrails commonly employed in curatives by physicians of the time.

The court doctor also says he once purchased a prescription for colic treatment from a woman who learned the recipe on a trip to Africa. Many of the remedies employed by ancient Greeks and Romans were taken from other cultures: whether learned on trips to far-off lands or purchased from Arab merchants who had traveled from the Far East to sell potent plants like iris, calamus, and cardamomum.

Said to be cousins of Jesus’s apostle Paul, sisters Zenais and Philomela studied medicine and opened a clinic for the poor at a time when male physicians charged exorbitant sums and catered to the wealthy. Similarly, Fabiola founded hospitals for the poor in Ostia and Rome. At a time when Romans had little concept or interest in charity, her institutions were revolutionary.

In China, the wu were shamen that practiced as spirit mediums and witch doctors. When their existence was first recorded during the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE), wu could be men or women, but during the Zhou Dynasty (1045-256 BCE) wu began to refer only to a female shaman or sorceress. Ch'un YU-yen was a noted woman obstetrician during the Han dynasty (206 BCE to 220 CE).

During the Song Dynasty, (10th to the 13th century), modern medicine emerged in tandem with rising patriarchal beliefs. Except for midwifery, women were increasingly shut out of practicing medicine. But there are some glorious exceptions. In addition to being a beloved (and apparently beautiful) abortionist, pharmacist, and obstetrician, Bai managed her own pharmacy and medical library. And the wealthy Mistress Wang served as the palace gynecologist.

It was common for relatives to apprentice with their family members in their trade; medicine was no exception. Many women practitioners are those who had a relation to pass down their knowledge. Fearing their own daughters would marry off and take the family’s hard-earned medical secrets along with them, many preferred to train their sons or daughters-in-law. One Chinese medical family of the 1400s included Mistress Jaing and her daughter-in-law Mistress Fang, renowned pediatric specialists. Jaing’s surgical intervention once saved the life of a child born without a rectal opening.

Rusa practiced Ayurvedic medicine in India, authoring a medical text on diseases of women that was later translated into Arabic in the 8th century.

By the Middle Ages in Europe, “the healing art” became part of the curriculum in monasteries and convent schools. Monks and nuns would tend medicinal herb gardens, dress soldiers’ battle wounds, and nurse the ill back to health.

Hildegard von Bingen (~1098-1179) was a Christian mystic, abbess, philosopher, composer, and writer who published nine works on religion and science. Her first medical text, Physica, contained nine books. Her second, Causae et Curae, had approximately 300 chapters. In those two texts Hildegard makes 437 claims of health benefits from 175 different plants. Cloves could treat gout, swollen intestines, stuffiness, and hiccups. For the “retention of the menses,” aka terminating a pregnancy, she prescribed a bath of fresh river water heated with warm tiles and filled with herbs like tansy, chrysanthemum, mullein, or feverfew.

After graduating from the renowned medical school in Salerno, Italy, in the 11th century, Trota authored a lengthy, three-section book on treating women’s ailments that remained a significant medical text for hundreds of years. Salerno produced many skilled medical women, including Mercuriade, who wrote four works on surgical pathology, Costanza Calenda, the daughter of the school dean who became a surgeon specializing in eye diseases, and skilled surgeon Francoise. As the school faded throughout the thirteenth century, so did the women doctors.

When churches began opening modern universities in Europe, it solidified medicine as a profession to be practiced by licensed men. Most schools didn’t admit women, but some were more amenable than others, often out of deference to family ties. In 1390, Italian physician Dorotea Bucca took over for her father as chair of medicine at the University of Bologna—a post she held for more than 40 years.

A relative scarcity of women in historical archives labeled as a professional medical practitioner is likely not because they did not exist, but rather because their activities were not recorded and their occupations not labeled as often as men’s were. It also points to the preference given by archives/archivists to written records, as opposed to oral histories, and to European cultures.

“Women's significant contribution to healthcare can be mapped out by looking at the domestic space that is largely left outside the histories of medieval medicine,” writes medical historian Montserrat Cabré in the journal Bulletin of the History of Medicine. “The caring meanings ascribed to the words women, mothers, midwives, and nurses … describe a continuum of practice whose origin is the household, from where it expands to the community.”

My goal for my book was to offer a detailed example of what it was like to try to become a woman doctor during a time when the very idea was scandalous. Theirs is the story of when the doors of medical schools were finally, fully opened to women—and remained that way. My book is a story, not a survey. As much as I would’ve loved to include every incredible woman in the history of medicine, there’s just so many, there wasn’t enough space. Even now, I’m panicking that I’ve forgotten to mention a country or culture or tradition in this article. There are so, so many and each one is more fascinating than the next. They all truly deserve books of their own.

Further Reading:

The Woman in the Shaman's Body: Reclaiming the Feminine in Religion and Medicine by Barbara Tedlock. Random House, 2009.

“Healing History, Women in Medicine,” Lady Science, by Abby Norman, January 18, 2017.

“Saints and Sinners: Women and the Practice of Medicine Throughout the Ages,” Journal of the American Medical Association, by Rhoda Wynn, February 2, 2000.

Science Beyond the West: A working group in the department of history and sociology of science at the University of Pennsylvania exploring ideas in the histories of science, medicine, and technology beyond North America and Western Europe.

More about me:

Amazon Author page

Goodreads Author page

Order my book: Women in White Coats: How the First Women Doctors Changed the World of Medicine, out March 2, 2021 from HarperCollins/Park Row Books.

Buy a *signed* hardback copy online at Newtown Bookshop.